Saffron/ja: Difference between revisions

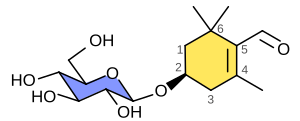

Created page with "===ファイトケミカルと感覚特性=== thumb|[[picrocrocin/ja|ピクロクロシンの構造: {| |- |{{Legend|#AEAEFF|β–D-グルコピラノース誘導体}} |- |{{Legend|#F5D76C|サフラナール部位}} |} ]] thumb|[[crocetin/ja|クロセチンとゲンチオビオースの間のエステル化反応。..." |

|||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

サフランには、[[ketone/ja|ケトン]]と[[aldehyde/ja|アルデヒド]]を主とする、約28種類の[[Volatile organic compound/ja|揮発性および芳香性化合物]]が含まれている。その主な芳香活性化合物は、サフランの香りの主成分である[[safranal/ja|サフラナール]]、4-ケトイソホロン、およびジヒドロオキソホロンである。サフランにはまた、[[zeaxanthin/ja|ゼアキサンチン]]、[[lycopene/ja|リコペン]]、様々なα-およびβ-[[carotene/ja|カロテン]]、そして最も生物学的に活性な成分である[[crocetin/ja|クロセチン]]とその[[glycoside/ja|配糖体]]であるクロシンを含む非揮発性の[[phytochemical/ja|ファイトケミカル]]も含まれる。クロセチンは他のカロテノイドよりも小さく、水溶性であるため、より迅速に吸収される。 | サフランには、[[ketone/ja|ケトン]]と[[aldehyde/ja|アルデヒド]]を主とする、約28種類の[[Volatile organic compound/ja|揮発性および芳香性化合物]]が含まれている。その主な芳香活性化合物は、サフランの香りの主成分である[[safranal/ja|サフラナール]]、4-ケトイソホロン、およびジヒドロオキソホロンである。サフランにはまた、[[zeaxanthin/ja|ゼアキサンチン]]、[[lycopene/ja|リコペン]]、様々なα-およびβ-[[carotene/ja|カロテン]]、そして最も生物学的に活性な成分である[[crocetin/ja|クロセチン]]とその[[glycoside/ja|配糖体]]であるクロシンを含む非揮発性の[[phytochemical/ja|ファイトケミカル]]も含まれる。クロセチンは他のカロテノイドよりも小さく、水溶性であるため、より迅速に吸収される。 | ||

サフランの黄色がかったオレンジ色は、主にα-クロシンによるものである。この[[crocin/ja|クロシン]]は''トランス''-[[crocetin/j|クロセチン]]ジ-(β-D-[[gentiobiose/ja|ゲンチオビオシル]])[[ester/ja|エステル]]であり、[[IUPAC nomenclature/ja|系統名]](IUPAC名)は8,8-ジアポ-8,8-カロテン酸である。これは、サフランの香りの根底にあるクロシンが、カロテノイドであるクロセチンのジゲンチオビオースエステルであることを意味する。クロシン自体は、クロセチンの[[glycosyl/ja|モノグリコシル]]またはジグリコシル[[polyene/ja|ポリエン]]エステルである[[hydrophile/ja|親水性]]のカロテノイドの一連の化合物である。クロセチンは[[conjugated system/ja|共役]]ポリエン[[carboxylic acid/ja|ジカルボン酸]]であり、[[Hydrophobe/ja|疎水性]]であるため油溶性である。クロセチンが、[[carbohydrate/ja|糖]]である2つの水溶性ゲンチオビオースと[[esterification/ja|エステル化]]されると、それ自体が水溶性である生成物が生じる。その結果生じるα-クロシンは、乾燥サフランの質量の10%以上を占める可能性のあるカロテノイド色素である。2つのエステル化されたゲンチオビオースが、α-クロシンを米料理のような水ベースの非脂肪性食品を着色するのに理想的なものとしている。 | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | <div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | ||

Revision as of 14:16, 15 September 2025

サフラン(/ˈsæfrən, -rɒn/)は、一般に「サフランクロッカス」として知られるクロッカス・サティヴスの花から取れる香辛料である。雌しべの鮮やかな紅色の柱頭と花柱(合わせて糸状体と呼ばれる)を摘み取り、乾燥させて、主に調味料や着色料として食品に使用する。サフランクロッカスはユーラシア大陸の大部分にわたって徐々に伝播し、その後、北アフリカ、北アメリカ、およびオセアニアの一部に持ち込まれた。

サフランの味とヨードホルムのような、あるいは干し草のような香りは、ファイトケミカルであるピクロクロシンとサフラナールに由来する。また、カロテノイド色素であるクロシンを含んでおり、料理や繊維に豊かな黄金色を与える。その品質は、黄色い花柱に対する赤い柱頭の割合によって等級が付けられており、地域によって異なり、効能と価値の両方に影響を与える。2024年現在、イランは世界のサフラン総生産量の約90%を生産している。サフランは1kgあたり5,000米ドル以上であり、長年にわたり世界で最も高価な香辛料である。

英語の単語「saffron」は、おそらく古フランス語のsafranに由来し、これはラテン語とペルシア語を経て、「金が連なる」を意味するzarparānという言葉に遡る。これは、不稔性で、人間によって伝播された、秋に開花する植物で、東地中海の野生種の子孫であり、日当たりの良い温帯気候で、香りのよい紫色の花と貴重な赤い柱頭のために栽培されてきた。サフランは主に料理用の香辛料や天然の着色料として使用され、伝統医学、染色、香水、宗教儀式においても歴史的に使用されてきた。

サフランは、ギリシャ、イラン、またはメソポタミアのいずれか、またはその近隣を起源としている可能性が高い。ユーラシア大陸全体で3,500年以上にわたって栽培・取引されており、文化交流や征服を通じてアジア中に広がった。その記録された歴史は、紀元前7世紀のアッシリアの植物学論文に記されている。

語源

英語のsaffronという単語の起源には、ある程度の不確実性がつきまとう。12世紀の古フランス語のsafranに由来する可能性があり、これはラテン語のsafranum、ペルシア語(زعفران、za'farān)を経て、最終的には「金が連なる」(花の黄金色の雄しべ、または風味として使用した際に生み出す黄金色のいずれかを示唆)を意味するペルシア語のzarparān (زَرپَران) に由来する。

種

概要

栽培種のサフランクロッカス(Crocus sativus)は、野生では見られない開花植物の多年草である。おそらくは「ワイルドサフラン」としても知られ、ギリシャ本土、エウボイア島、クレタ島、スキロス島、そしてキクラデス諸島の一部を原産とする、東地中海の秋咲き種のCrocus cartwrightianusの子孫であるとされている。類似種のC. thomasiiやC. pallasiiもまた、他の可能性のある祖先と考えられていた。種子を生産できない遺伝的に単一のクローンとして、ユーラシア大陸の大部分にわたって人間によってゆっくりと伝播していった。サフランの起源については、イラン、ギリシャ、メソポタミア、カシミールなど、様々な説が提唱されている。

これは不稔性の三倍体であり、各個体の遺伝子構成は3つの相同な染色体のセットから成ることを意味する。C. sativusは1セットあたり8個の染色体を持ち、合計で24個となる。不稔性のため、C. sativusの紫色の花は生存可能な種子を生産しない。繁殖は人間の助けに依存している。地下にある球茎、すなわち球根に似たデンプンを貯蔵する器官の塊を掘り起こし、分割して植え直さなければならない。球茎は1シーズン生存し、栄養繁殖によって最大10個の「小球茎」を生成し、翌シーズンには新しい植物に成長することができる。このコンパクトな球茎は小さな茶色の球体で、直径は最大5 cm (2 in)に達し、平らな底を持ち、平行な繊維が密集したマットで覆われている。この覆いは「球茎の外皮」と呼ばれる。球茎はまた、植物の首から上5 cm (2 in)まで成長する、薄くて網状の垂直な繊維を持つ。

この植物は、鱗片葉として知られる、5~11枚の白く光合成をしない葉を出す。これらの膜のような構造は、クロッカスの花の上で芽を出し成長する5〜11枚の真の葉を覆い、保護する。後者は、薄く、まっすぐで、刃のような緑色の葉で、直径は1–3 mm (1⁄32–1⁄8 in)であり、花が開いた後に広がる(「後花性」)か、開花と同時に広がる(「同時性」)かのいずれかである。C. sativusの鱗片葉は、比較的生育期の早い段階で植物に水をやると、開花前に現れるのではないかと一部では考えられている。その花軸、すなわち花をつける構造は、苞葉、つまり特殊な葉を持ち、花茎から芽を出す。後者は花柄として知られている。春に休眠した後、この植物は、それぞれ長さが最大40 cm (16 in)に達する真の葉を出す。他のほとんどの開花植物が種子を放出した後の10月になって初めて、その鮮やかに着色された花が発達する。花の色は、淡いライラックのパステル調の色から、より濃く、より縞模様の入った藤色まで様々である。花は甘い、ハチミツのような香りを放つ。開花時には、植物の高さは20–30 cm (8–12 in)になり、最大4つの花をつける。各花からは、長さ25–30 mm (1–1 3⁄16 in)の3つに分かれた花柱が伸びる。各先端は鮮やかな深紅色の柱頭で終わる。これは心皮の末端部分である。

栽培

野生では知られていないサフランクロッカスは、おそらくCrocus cartwrightianusの子孫である。これは「自家不和合性」で雄性不稔性の三倍体であり、減数分裂が異常なため、自力での有性生殖が不可能である。すべての繁殖は、スタータークローンを手作業で「分割して植える」か、種間交配による栄養繁殖によって行われる。

Crocus sativusは、北米のチャパラルに表面的には似たマキ、そして高温で乾燥した夏の風が半乾燥地を吹き抜ける同様の気候で生育する。それでも寒い冬を乗り切ることができ、−10 °C (14 °F)という低さの霜や、短い間の積雪にも耐える。一部の報告では、サフランは-22℃から40℃までの気温範囲に耐えられると示唆されている。年間降水量が平均1,000–1,500 mm (40–60 in)のカシミールのような湿潤な環境の外で栽培する場合は、灌漑が必要である。ギリシャ(年間500 mm or 20 in)やスペイン(400 mm or 16 in)のサフラン栽培地域は、主要な栽培地であるイランの地域よりもはるかに乾燥している。これを可能にしているのは、現地の雨季のタイミングであり、恵まれた春の雨と乾燥した夏が最適である。開花の直前の雨はサフランの収量を増加させる。開花中の雨や寒い天候は病気を助長し、収量を減少させる。継続的に湿潤で高温な状態は作物に害を及ぼし、ウサギ、ネズミ、鳥は球茎を掘り起こすことによって被害を引き起こす。線虫、葉のさび病、球茎腐敗病は他の脅威となる。しかし、Bacillus subtilisを接種することで、球茎の成長を早め、柱頭のバイオマス収量を増やすことにより、栽培者に何らかの利益をもたらす可能性がある。

この植物は日陰の条件では生育が悪く、日当たりの良い場所で最もよく育つ。日当たりに向かって傾斜した畑が最適である(すなわち、北半球では南向きの斜面)。植え付けは北半球ではほとんどが6月に行われ、球茎は深さ7–15 cm (3–6 in)に植えられる。その根、茎、葉は10月から2月の間に成長することができる。気候と合わせて、植え付けの深さと球茎の間隔は、収量を決定する上で重要な要素である。深く植えられた母球茎は、より高品質なサフランを生み出すが、花の芽や娘球茎の形成は少なくなる。イタリアの栽培者は、深さ15 cm (6 in)、列の間隔を2–3 cm (3⁄4–1 1⁄4 in)にして植えることで、糸状体の収量を最適化している。深さ8–10 cm (3–4 in)は、花と球茎の生産を最適化する。ギリシャ、モロッコ、スペインの栽培者は、それぞれの地域に適した独自の深さと間隔を採用している。

C. sativusは、有機物含有量が高い、脆く、緩く、低密度の、水はけが良く、水管理の行き届いた粘土石灰質の土壌を好む。伝統的な高畝は水はけを良くする。土壌の有機物含有量は、歴史的には20–30 tonnes per hectare (9–13 short tons per acre)ほどの肥料を施用することで高められてきた。その後、これ以上の肥料の施用なしに球茎が植えられた。夏の間休眠期間を過ごした後、球茎は細い葉を出し、初秋に芽を出し始める。中秋になって初めて開花する。収穫は必然的に迅速に行わなければならない。夜明けに開花した後、花は日が経つにつれて急速にしおれる。すべての植物は1〜2週間の間に開花する。柱頭は抽出後すぐに乾燥させ、(できれば)気密容器に密閉する。

収穫

サフランの小売価格が高いのは、労働集約型の収穫方法によるもので、これには440,000 手摘みのサフランの柱頭 per kilogram (200,000 stigmas/lb)、つまり150,000 クロッカスの花 per kilogram (70,000 flowers/lb)が必要となる。150,000本の花を摘むには40時間の労働が必要である。

摘みたてのクロッカスの花1本からは、平均30 mgの生のサフラン、または7 mgの乾燥サフランが採れる。およそ150本の花から1 g (1⁄32 oz)の乾燥サフランの糸状体が採れる。12 g (7⁄16 oz)の乾燥サフランを生産するには、450 g (1 lb)の花が必要となる。生のサフランから得られる乾燥香辛料の収量はわずか13 g/kg (0.2 oz/lb)である。

香辛料

ファイトケミカルと感覚特性

サフランには、ケトンとアルデヒドを主とする、約28種類の揮発性および芳香性化合物が含まれている。その主な芳香活性化合物は、サフランの香りの主成分であるサフラナール、4-ケトイソホロン、およびジヒドロオキソホロンである。サフランにはまた、ゼアキサンチン、リコペン、様々なα-およびβ-カロテン、そして最も生物学的に活性な成分であるクロセチンとその配糖体であるクロシンを含む非揮発性のファイトケミカルも含まれる。クロセチンは他のカロテノイドよりも小さく、水溶性であるため、より迅速に吸収される。

サフランの黄色がかったオレンジ色は、主にα-クロシンによるものである。このクロシンはトランス-クロセチンジ-(β-D-ゲンチオビオシル)エステルであり、系統名(IUPAC名)は8,8-ジアポ-8,8-カロテン酸である。これは、サフランの香りの根底にあるクロシンが、カロテノイドであるクロセチンのジゲンチオビオースエステルであることを意味する。クロシン自体は、クロセチンのモノグリコシルまたはジグリコシルポリエンエステルである親水性のカロテノイドの一連の化合物である。クロセチンは共役ポリエンジカルボン酸であり、疎水性であるため油溶性である。クロセチンが、糖である2つの水溶性ゲンチオビオースとエステル化されると、それ自体が水溶性である生成物が生じる。その結果生じるα-クロシンは、乾燥サフランの質量の10%以上を占める可能性のあるカロテノイド色素である。2つのエステル化されたゲンチオビオースが、α-クロシンを米料理のような水ベースの非脂肪性食品を着色するのに理想的なものとしている。

The bitter glucoside picrocrocin is responsible for saffron's pungent flavour. Picrocrocin (chemical formula: C

16H

26O

7; systematic name: 4-(β-D-glucopyranosyloxy)-2,6,6-trimethylcyclohex-1-ene-1-carbaldehyde) is a union of an aldehyde sub-molecule known as safranal (systematic name: 2,6,6-trimethylcyclohexa-1,3-diene-1-carbaldehyde) and a carbohydrate. It has insecticidal and pesticidal properties, and may comprise up to 4% of dry saffron. Picrocrocin is a truncated version of the carotenoid zeaxanthin that is produced via oxidative cleavage, and is the glycoside of the terpene aldehyde safranal.

When saffron is dried after its harvest, the heat, combined with enzymatic action, splits picrocrocin to yield D–glucose and a free safranal molecule. Safranal, a volatile oil, gives saffron much of its distinctive aroma. Safranal is less bitter than picrocrocin and may comprise up to 70% of dry saffron's volatile fraction in some samples. A second molecule underlying saffron's aroma is 2-hydroxy-4,4,6-trimethyl-2,5-cyclohexadien-1-one, which produces a scent described as saffron, dried hay-like. Chemists find this is the most powerful contributor to saffron's fragrance, despite its presence in a lesser quantity than safranal. Dry saffron is highly sensitive to fluctuating pH levels, and rapidly breaks down chemically in the presence of light and oxidising agents. It must, therefore, be stored in air-tight containers to minimise contact with atmospheric oxygen. Saffron is somewhat more resistant to heat.

Grades and ISO 3632 categories

Saffron is not all of the same quality and strength. Strength is related to several factors, including age and the amount of yellow style picked relative to red stigma, as colour and flavour are concentrated in the latter.

Saffron from Iran, Spain, and Kashmir is classified into various grades according to the proportion of stigma to style it contains. Grades of Iranian saffron are: sargol (Persian: سرگل, red stigma tips only, strongest grade), pushal or pushali (red stigmas plus some yellow style, lower strength), "bunch" saffron (red stigmas plus large amount of yellow style, presented in a tiny bundle like a miniature wheatsheaf) and konge (yellow style only, claimed to have aroma but with very little, if any, colouring potential). Grades of Spanish saffron are coupé (the strongest grade, like Iranian sargol), mancha (like Iranian pushal), and in order of further decreasing strength rio, standard and sierra saffron. The word mancha in the Spanish classification can have two meanings: a general grade of saffron or a very high quality Spanish-grown saffron from a specific geographical origin. Real Spanish-grown La Mancha saffron has PDO protected status, which is displayed on the product packaging. Spanish growers fought hard for Protected Status because they felt that imports of Iranian saffron re-packaged in Spain and sold as "Spanish Mancha saffron" were undermining the genuine La Mancha brand. Similar was the case in Kashmir where imported Iranian saffron is mixed with local saffron and sold as "Kashmir brand" at a higher price. In Kashmir, saffron is mostly classified into two main categories called mongra (stigma alone) and lachha (stigmas attached with parts of the style). Countries producing less saffron do not have specialised words for different grades and may only produce one grade. Artisan producers in Europe and New Zealand have offset their higher labour charges for saffron harvesting by targeting quality, only offering extremely high-grade saffron.

In addition to descriptions based on how the saffron is picked, saffron may be categorised under the international standard ISO 3632 after laboratory measurement of crocin (responsible for saffron's colour), picrocrocin (taste), and safranal (fragrance or aroma) content. However, often there is no clear grading information on the product packaging and little of the saffron readily available in the UK is labelled with ISO category. This lack of information makes it hard for customers to make informed choices when comparing prices and buying saffron.

Under ISO 3632, determination of non-stigma content ("floral waste content") and other extraneous matter such as inorganic material ("ash") are also key. Grading standards are set by the International Organization for Standardization, a federation of national standards bodies. ISO 3632 deals exclusively with saffron and establishes three categories: III (poorest quality), II, and I (finest quality). Formerly there was also category IV, which was below category III. Samples are assigned categories by gauging the spice's crocin and picrocrocin content, revealed by measurements of specific spectrophotometric absorbance. Safranal is treated slightly differently and rather than there being threshold levels for each category, samples must give a reading of 20–50 for all categories.

These data are measured through spectrophotometry reports at certified testing laboratories worldwide. Higher absorbances imply greater levels of crocin, picrocrocin and safranal, and thus a greater colouring potential and therefore strength per gram. The absorbance reading of crocin is known as the "colouring strength" of that saffron. Saffron's colouring strength can range from lower than 80 (for all category IV saffron) up to 200 or greater (for category I). The world's finest samples (the selected, most red-maroon, tips of stigmas picked from the finest flowers) receive colouring strengths in excess of 250, making such saffron over three times more powerful than category IV saffron. Market prices for saffron types follow directly from these ISO categories. Sargol and coupé saffron would typically fall into ISO 3632 category I. Pushal and Mancha would probably be assigned to category II. On many saffron packaging labels, neither the ISO 3632 category nor the colouring strength (the measurement of crocin content) is displayed.

However, many growers, traders, and consumers reject such lab test numbers. Some people prefer a more holistic method of sampling batches of threads for taste, aroma, pliability, and other traits in a fashion similar to that practised by experienced wine tasters.

Adulteration

Despite attempts at quality control and standardisation, an extensive history of saffron adulteration, particularly among the cheapest grades, continues into modern times. Adulteration was first documented in Europe's Middle Ages, when those found selling adulterated saffron in Nuremberg were executed under the Safranschou code. Typical methods include mixing in extraneous substances like beetroot, pomegranate fibres, red-dyed silk fibres, or the saffron crocus's tasteless and odourless yellow stamens. Other methods included dousing saffron fibres with viscid substances like honey or vegetable oil to increase their weight. Powdered saffron is more prone to adulteration, with turmeric, paprika, and other powders used as diluting fillers. Adulteration can also consist of selling mislabelled mixes of different saffron grades. Thus, high-grade Kashmiri saffron is often sold and mixed with cheaper Iranian imports; these mixes are then marketed as pure Kashmiri saffron. Safflower is a common substitute sometimes sold as saffron. The spice is reportedly counterfeited with horse hair, corn silk, or shredded paper. Tartrazine or sunset yellow dyes have been used to colour counterfeit powdered saffron.

In recent years, saffron adulterated with the colouring extract of gardenia fruits has been detected in the European market. This form of fraud is difficult to detect due to the presence of flavonoids and crocines in the gardenia-extracts similar to those naturally occurring in saffron. Detection methods have been developed by using HPLC and mass spectrometry to determine the presence of geniposide, a compound present in the fruits of gardenia, but not in saffron.

Types

The various saffron crocus cultivars give rise to thread types that are often regionally distributed and characteristically distinct. Varieties (not varieties in the botanical sense) from Spain, including the tradenames "Spanish Superior" and "Creme", are generally mellower in colour, flavour, and aroma; they are graded by government-imposed standards. Italian varieties are slightly more potent than Spanish. Greek saffron produced in the town of Krokos is PDO protected due to its particularly high-quality colour and strong flavour. Various "boutique" crops are available from New Zealand, France, Switzerland, England, the United States, and other countries—some of them organically grown. In the US, Pennsylvania Dutch saffron—known for its "earthy" notes—is produced in small quantities.

Consumers may regard certain cultivars as "premium" quality. The "Aquila" saffron, or zafferano dell'Aquila, is defined by high safranal and crocin content, distinctive thread shape, unusually pungent aroma, and intense colour; it is grown exclusively on eight hectares in the Navelli Valley of Italy's Abruzzo region, near L'Aquila. It was first introduced to Italy by a Dominican friar from inquisition-era Spain. But the biggest saffron cultivation in Italy is in San Gavino Monreale, Sardinia, where it is grown on 40 hectares, representing 60% of Italian production; it too has unusually high crocin, picrocrocin, and safranal content.

Another is the "Mongra" or "Lacha" saffron of Kashmir (Crocus sativus 'Cashmirianus'), which is among the most difficult for consumers to obtain. Repeated droughts, blights, and crop failures in Kashmir combined with an Indian export ban, contribute to its prohibitive overseas prices. Kashmiri saffron is recognizable by its dark maroon-purple hue, making it among the world's darkest. In 2020, Kashmir Valley saffron was certified with a geographical indication from the Government of India.

Almost all saffron grows in a belt from Spain in the west to India in the east. Iran is responsible for around 88% of global production. In 2024, Iran was the largest producer of saffron, with Afghanistan as the second largest. Saffron is cultivated in 26 of Afghanistan's 34 provinces, with most production concentrated in Herat.

Spain is the third largest producer, while the United Arab Emirates, Greece, the Indian subcontinent and Morocco are among minor producers.

Trade

Saffron prices at wholesale and retail rates range from $1,100–$11,000/kg ($500–$5,000/lb). In Western countries, the average retail price in 1974 was $2,200/kg ($1,000/lb). In February 2013, a retail bottle containing 1.7 g (1⁄16 oz) could be purchased for $16.26 or the equivalent of $9,560/kg ($4,336/lb), or as little as about $4,400/kg ($2,000/lb) in larger quantities. There are between 150,000 and 440,000 threads /kg (70,000 and 200,000 threads/lb). Vivid crimson colouring, slight moistness, elasticity, and lack of broken-off thread debris are all traits of fresh saffron.

Uses

| Nutritional value per 1 tbsp (2.1 g) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 27 kJ (6.5 kcal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1.37 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dietary fibre | 0.10 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

0.12 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Saturated | 0.03 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Trans | 0.00 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monounsaturated | 0.01 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Polyunsaturated | 0.04 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

0.24 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other constituents | Quantity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Water | 0.25 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults, except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The primary use of saffron is in food and drink preparation. Saffron has a long history of use in traditional medicine. Saffron has also been used as a fabric dye, particularly in China and India, and in perfumery. It is used for religious purposes in India. It is one of the ingredients used in the making of Arabic coffee in Saudi Arabia.

In the European E number categorisation for food elements and additives, Saffron is coded as E164.

Consumption

Nutrition

Dried saffron is 65% carbohydrates, 6% fat, 11% protein (table) and 12% water. In one tablespoon (2 grams; a quantity much larger than is likely to be ingested in normal use) manganese is present as 29% of the Daily Value, while other micronutrients have negligible content (table).Toxicity

Ingesting less than 1.5 g (1⁄16 oz) of saffron is not toxic for humans, but doses greater than 5 g (3⁄16 oz) can become increasingly toxic. Mild toxicity includes dizziness, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, whereas at higher doses there can be reduced platelet count and spontaneous bleeding.

Storage

Saffron will not spoil, but will lose flavour within six months if not stored in an airtight, cool and dark place. Freezer storage can maintain flavour for up to two years.

Research

Dietary supplementation with saffron is under preliminary research to assess its potential effect on depression and anxiety.

History

Saffron likely originated in Iran, Greece, Mesopotamia, states that it was domesticated in or near Greece during the Bronze Age. C. sativus is probably a triploid form of Crocus cartwrightianus, which is also known as "wild saffron". Saffron crocus was slowly propagated by humans throughout much of Eurasia and was later brought to parts of North Africa, North America, and Oceania.

Several wild species of Crocus similar to the commercial plant are known to have been harvested in recent times for use as saffron. Crocus ancyrensis was used to make saffron in Sivas in Central Turkey, the corms were also eaten. Crocus cartwrightianus was harvested on Andros in the islands of the Cyclades, for medicinal purposes and the stigmas for making a pigment called Zafran. Crocus longiflorus stigmas were used for saffron in Sicily. Crocus thomasii stigmas were used to flavour dishes around Taranto, South Italy. In Syria the stigmas of an unknown wild species were collected by women and children, sun-dried and pressed into small tablets which were sold in the Bazaars. Not all ancient depictions or descriptions of saffron spice or flowers are certain to be the same species as the modern commercial species used for spice.

West Asia

Documentation of saffron's use over the span of 3,500 years has been uncovered. Saffron-based pigments have indeed been found in 50,000-year-old depictions of prehistoric places in northwest Iran. The Sumerians later used wild-growing saffron in their remedies and magical potions. It was also known in ancient Egypt, as indicated by a 2000 BC papyrus. Saffron was an article of long-distance trade before the Minoan palace culture's 2nd millennium BC peak. Ancient Persians cultivated Persian saffron (Crocus sativus var. haussknechtii now called Crocus haussknechtii by botanists) in Derbent, Isfahan, and Khorasan by the 10th century BC. At such sites, saffron threads were woven into textiles, ritually offered to divinities, and used in dyes, perfumes, medicines, and body washes. Saffron threads would thus be scattered across beds and mixed into hot teas as a curative for bouts of melancholy. Non-Persians also feared the Persians' usage of saffron as a drugging agent and aphrodisiac.

Saffron is featured in trade lists from Mari, Syria, is described in a 7th-century BC Assyrian botanical reference compiled under Ashurbanipal, and is listed among other aromatic plants in the Hebrew Bible, in Song of Songs 4:14. During his Asian campaigns, Alexander the Great used Persian saffron in his infusions, rice, and baths as a curative for battle wounds. Alexander's troops imitated the practice from the Persians and brought saffron-bathing to Greece.

South Asia

East Asia

Some historians believe that saffron came to China with Mongol invaders from Persia. Yet it is mentioned in ancient Chinese medical texts, including the forty-volume Shennong Bencaojing, a pharmacopoeia written around 300–200 BC. Traditionally credited to the legendary Yan Emperor and the deity Shennong, it discusses 252 plant-based medical treatments for various disorders. Nevertheless, around the 3rd century AD, the Chinese were referring to it as having a Kashmiri provenance. According to the herbalist Wan Zhen, "the habitat of saffron is in Kashmir, where people grow it principally to offer it to the Buddha". Wan also reflected on how it was used in his time: "The flower withers after a few days, and then the saffron is obtained. It is valued for its uniform yellow colour. It can be used to aromatise wine."

South East Mediterranean

Minoan depictions of saffron are now considered to be Crocus cartwrightianus. The Minoans portrayed saffron in their palace frescoes by 1600–1500 BC; they hint at its possible use as a therapeutic drug. Ancient Greek legends told of sea voyages to Cilicia, where adventurers sought what they believed were the world's most valuable threads. Another legend tells of Crocus and Smilax, whereby Crocus is bewitched and transformed into the first saffron crocus. Ancient perfumers in Egypt, physicians in Gaza, townspeople in Rhodes, and the Greek hetaerae courtesans used saffron in their scented waters, perfumes and potpourris, mascaras and ointments, divine offerings, and medical treatments.

In late Ptolemaic Egypt, Cleopatra used saffron in her baths so that lovemaking would be more pleasurable. Egyptian healers used saffron as a treatment for all varieties of gastrointestinal ailments. Saffron was also used as a fabric dye in such Levantine cities as Sidon and Tyre in Lebanon. Aulus Cornelius Celsus prescribes saffron in medicines for wounds, cough, colic, and scabies, and in the mithridatium.

Western Europe

Saffron was a notable ingredient in certain Roman recipes such as jusselle and conditum. Such was the Romans' love of saffron that Roman colonists took it with them when they settled in southern Gaul, where it was extensively cultivated until Rome's fall. With this fall, European saffron cultivation plummeted. Competing theories state that saffron only returned to France with 8th-century AD Moors or with the Avignon papacy in the 14th century AD. Similarly, the spread of Islamic civilisation may have helped reintroduce the crop to Spain and Italy.

The 14th-century Black Death caused demand for saffron-based medicaments to peak, and Europe imported large quantities of threads via Venetian and Genoan ships from southern and Mediterranean lands such as Rhodes. The theft of one such shipment by noblemen sparked the fourteen-week-long Saffron War. The conflict and resulting fear of rampant saffron piracy spurred corm cultivation in Basel; it thereby grew prosperous. The crop then spread to Nuremberg, where endemic and insalubrious adulteration brought on the Safranschou code—whereby culprits were variously fined, imprisoned, and executed. Meanwhile, cultivation continued in southern France, Italy, and Spain.

Direct archaeological evidence of mediaeval saffron consumption in Scandinavia comes from the wreck of the royal Danish-Norwegian flagship, Gribshunden. The ship sank in 1495 while on a diplomatic mission to Sweden. Excavations in 2021 revealed concentrations of saffron threads and small "pucks" of compressed saffron powder, along with fresh ginger, cloves, and pepper. Surprisingly, the saffron retained its distinctive odour even after more than 500 years of submersion in the Baltic Sea.

The Essex town of Saffron Walden, named for its new specialty crop, emerged as a prime saffron growing and trading centre in the 16th and 17th centuries but cultivation there was abandoned; saffron was re-introduced around 2013 as well as other parts of the UK (Cheshire).

The Americas

Europeans introduced saffron to the Americas when immigrant members of the Schwenkfelder Church left Europe with a trunk containing its corms. Church members had grown it widely in Europe. By 1730, the Pennsylvania Dutch cultivated saffron throughout eastern Pennsylvania. Spanish colonies in the Caribbean bought large amounts of this new American saffron, and high demand ensured that saffron's list price on the Philadelphia commodities exchange was equal to gold. Trade with the Caribbean later collapsed in the aftermath of the War of 1812, when many saffron-bearing merchant vessels were destroyed. Yet the Pennsylvania Dutch continued to grow lesser amounts of saffron for local trade and use in their cakes, noodles, and chicken or trout dishes. American saffron cultivation survives into modern times, mainly in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania.

Afghanistan

Saffron has a long history in Afghanistan, with cultivation believed to date back to before Alexander the Great's conquest of the Persian Empire. Due to prolonged droughts, conflict, and shifts in agricultural focus, saffron farming declined for centuries. Cultivation resumed in the early 2000s as an alternative to opium poppy farming, supported by international organizations and the Afghan government. According to Afghanistan’s Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation, and Livestock, production increased from 20 metric tons in 2022 to 46 metric tons in 2024. Key export markets include India, Europe, and the United States, where Afghan saffron is prized for its high quality.

Saffron cultivation contributes significantly to Afghanistan’s economy, supporting thousands of farmers, particularly women. Over 80% of the saffron workforce consists of women, who primarily handle harvesting and processing. The sector has provided employment opportunities for over 40,000 people, playing a role in agricultural sustainability and rural development.

Afghan saffron is known for its deep red color, strong aroma, and high crocin content, a compound that determines color intensity. It has been ranked among the highest quality saffron varieties in recent years with a 310 Crocin color quality based on ISO 3632.2 standards.

ギャラリー

-

クロッカスの花、早咲き

-

クロッカスの栽培

外部リンク

| この記事は、クリエイティブ・コモンズ・表示・継承ライセンス3.0のもとで公表されたウィキペディアの項目Saffron(3 September 2025, at 15:38編集記事参照)を翻訳して二次利用しています。 |