漢方薬

| 下記シリーズの一部分 |

| History of science and technology in China/ja |

|---|

|

| この記事は、下記シリーズの一部分 |

| Alternative medicine/ja |

|---|

|

漢方(簡体字:中药学、繁体字:中藥学、ピンイン:zhōngyào xué)とは、中国伝統医学(TCM)における治療の大部分を占める漢方治療の理論である。Nature誌の社説は、中医学を「疑似科学に満ちている」と評し、中医学が多くの治療法を提供できていない最も明白な理由は、その治療法の大半が論理的な作用機序を持っていないからだと述べている。

本草学という言葉は誤解を招きやすいが、植物成分が圧倒的に多く使用されている一方で、動物性、人体性、鉱物性のものも利用されており、その中には有毒なものもある。黄帝内経では、それらは毒藥(ピンイン:dúyào)と呼ばれ、毒素、毒、薬を意味する。ポール・U・ウンシュルドは、これはギリシャ語のpharmakonと語源が似ていると指摘し、「薬学的」という言葉を使っている。したがって、药(ピンイン:yào)の訳語としては、(薬草の代わりに)「薬用」という用語が通常好まれる。

伝統的な漢方治療の有効性に関する研究は質が低く、しばしばバイアスに汚染されており、有効性に関する厳密な証拠はほとんどない。潜在的に有毒な漢方薬の数々には懸念がある。

歴史

中国の薬草は何世紀にもわたって使用されてきた。最も古い文献の中には、紀元前168年に封印された『馬王堆』から発見された写本『52の病気のためのレシピ』に代表される、特定の病気に対する処方のリストがある。

伝統的に認められている最初の漢方医は、紀元前2800年頃に生きたとされる神話の神のような人物、神農( Shénnóng、神农)である。彼は何百種類もの薬草を味わい、薬草や毒草に関する知識を農民に教えたと言われている。彼が著した『神農本草経』は、中国最古の漢方薬の本とされている。365種の根、草、木、毛皮、動物、石を3種類の生薬に分類している:

- 「上薬」カテゴリーには、複数の病気に有効な生薬が含まれ、身体のバランスを維持・回復させる働きがほとんどである。副作用はほとんどない。

- トニックとブースターで構成されるカテゴリーで、その摂取は長期化してはならない。

- 通常、少量しか服用せず、特定の病気の治療のみに使用する物質のカテゴリーである。

「神農本草経』の原文は失われてしまったが、現存する翻訳がある。本当の成立年代は前漢末(紀元前1世紀)と考えられている。

『寒損病雑病論』は、張仲景が漢代末期の196年から220年にかけて編纂した。薬物処方に重点を置き、陰陽五行と薬物療法を組み合わせた最初の医学書である。この処方はまた、症状を臨床的に有用な「パターン」(zheng, 證)に分類し、治療の対象とした中国最古の医学書でもある。時代とともに何度も変遷を経て、現在では2種類の書物として流通している: 『冷え症論』と『金匱要略』は、11世紀の宋代に別々に編集された。

7世紀の唐代に編纂された漢方医学書[[:en:Yaoxing Lun|药性论; 藥性論; 'Treatise on the Nature of Medicinal Herbs']]のように、後世の書物も増補された。

数世紀にわたり、治療における重点の変化があった。『内経素問』の第74章を含む一節は、王冰(Wáng Bīng)が765年の版で追加したものである。そこにはこう書かれている: 主病之謂君,佐君之謂臣,應臣之謂使,非上下三品之謂也、 君主を補佐する者を大臣と呼び、大臣に従う者を特使(補佐官)と呼び、上下の三品(資質)を呼ばない。 「この最後の部分は、これらの三人の支配者は、先に述べた三階級の臣下ではないことを述べていると解釈される。この章は特に、より強引なアプローチを概説している。その後、張子和[張子漳漳、別名張叢珍](1156-1228)は、頓服の使いすぎを批判する「攻撃派」を創始したとされている。

これらの後世の著作の中で最も重要なものは、李時珍が明代に編纂した『本草綱目(Bencao Gangmu)』であろう。

漢方薬の使用は、中世に西アジアやイスラム諸国で流行した。それらは東洋から西洋へとシルクロードを通じて取引された。シナモン、ジンジャー、ルバーブ、ナツメグ、キュベブは、中世イスラムの医学者であるラゼス(854-925 CE)、ハーリー・アッバース(930-994 CE)、アヴィセンナ(980-1037 CE)によって漢方薬として言及されている。また、中国医学とイスラム医学におけるこれらのハーブの臨床使用には複数の類似点があった。

原材料

中国ではおよそ13,000種類の薬草が使用されており、古代の文献には100,000種類以上の薬膳レシピが記録されている。植物の成分やエキスが圧倒的に多く使われている。1941年に出版された古典的な『伝統薬物ハンドブック』には、517種類の薬物が記載されているが、そのうち動物の部位は45種類、鉱物は30種類に過ぎない。薬として使われる多くの植物については、生育に適した場所や地域だけでなく、植え付けや収穫の時期についても詳細な指示が伝えられている。

牛の胆石のように、薬として使われる動物の部位の中には、かなり奇妙なものもある。

さらに『本草綱目』には、骨、爪、毛、フケ、耳垢、歯の不純物、糞、尿、汗、臓器など、人体に由来する35種類の伝統的な漢方薬の使用が記されているが、そのほとんどはすでに使用されていない。

調整法

煎じ薬

一般的に、一回分の薬草は約9~18種類の物質の煎じ薬として調製される。その中には主薬となるものもあれば、副薬となるものもある。副薬の中でも、最大で3つのカテゴリーに分けることができる。いくつかの成分は、主成分の毒性や副作用を打ち消すために加えられる。その上、薬によっては触媒として他の物質の使用を必要とする。

中国特許薬

中国特許薬(中成药;中成藥;zhōngchéng yào)は、伝統的な漢方薬の一種である。標準化されたハーブ処方である。古来、丸薬は数種類の薬草やその他の成分を組み合わせて作られ、それらを乾燥させて粉にしたものであった。その後、結合剤と混ぜ合わせ、手作業で丸薬にした。結合剤は伝統的に蜂蜜だった。しかし、現代のティーピルは、ステンレス製の抽出器で抽出され、使用するハーブによって水煎じか水-アルコール煎じになる。必要な成分を保つため、低温(摂氏100度以下)で抽出される。抽出された液体はさらに濃縮され、ハーブの原料の1つである生のハーブパウダーが混合され、ハーブの生地が形成される。この生地を機械で細かく裁断し、滑らかで安定した外観にするために少量の賦形剤を加え、紡いで錠剤にする。

これらの医薬品は、伝統的な意味での特許は取得していない。処方の独占権は誰にもない。その代わり、「特許」は処方の標準化を意味する。中国では、同じ名前の中国特許薬はすべて同じ成分比率で、法律で定められた中国薬局方に従って製造される。しかし、欧米諸国では、同じ名称の特許医薬品の成分比率にばらつきがあったり、まったく異なる成分であったりすることもある。

いくつかの漢方薬の製造業者は、米国や欧州の市場で自社製品を薬物として販売するため、FDAの臨床試験を進めている。

漢方エキス

漢方エキスは、薬草の煎じ薬を粒状または粉末状に凝縮したものである。漢方エキスは特許薬と同様、患者にとって服用しやすく便利である。業界の抽出基準は5:1であり、これは原料5ポンドに対して1ポンドの漢方エキスが得られることを意味する。

分類

伝統的な漢方薬を分類する方法はいくつかある:

- 四气; 四氣; sìqì

- 五味; wǔwèi

- 经络; 經絡; jīngluò

- 具体的な機能。

四気

四気とは、熱性、温性、涼性、寒性、中性である。熱性・温性の薬草は寒性の病気に、涼性・寒性の薬草は熱性の病気に用いられる。

五味

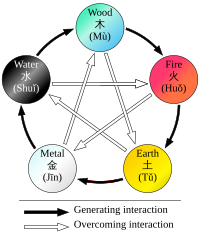

五味とは、辛味、甘味、苦味、酸味、塩味のことである。また、物質は複数の味を持つこともあれば、何も持たない(すなわち淡白な味)こともある。五味はそれぞれ臓腑のひとつに対応し、臓腑は五相のひとつに対応する: 塩味は「下方に排出し、硬い塊を軟らかくする」、甘味は「補い、調和し、潤す」、辛味は「発汗を促し、気血に作用する」、酸味は「収斂(涩; 澀)の性質がある」、苦味は「熱を排出し、腸を浄化し、湿を除去する」と考えられている。

特定の機能

これらのカテゴリーには主に以下が含まれる:

- 体の表面の邪気の解放と解消

- 熱を取り除く

- 排水または沈殿

- 風による湿気の発散

- 湿気を変える

- 水の移動を促進し、湿気を浸透させる。

- 体内を暖める

- 気を整える。

- 食品を拡散させる。

- 虫を出す。

- 止血する。

- 血を速め、#Xueうっ血を取り除く。

- 痰を化し、咳を止め、喘鳴を静める。

- 心を鎮める。

- 肝を静めて風を除く、または肝を静めて風を除く。

- 開口

- 補気:補気、補血、補陰、補陽を含む。

- 収縮を促す、または固定し、収縮させる。

- 嘔吐を誘発する。

- 外用物質

命名法

多くのハーブは、その独特な外観から名前を得ている。そのような名前の例には、ニウシ(牛膝、Radix cyathulae seu achyranthis)があり、「牛の膝」とも呼ばれ、大きな関節が牛の膝に似ているかのようである。また、白木耳(雲耳、Fructificatio tremellae fuciformis)は「白い木耳」とも呼ばれ、白くて耳のような形状をしている。グウジ(狗脊、Rhizoma cibotii)は「犬の背骨」とも呼ばれ、犬の背骨に似ている。

Color

Color is not only a valuable means of identifying herbs, but in many cases also provides information about the therapeutic attributes of the herb. For example, yellow herbs are referred to as huang (yellow) or jin (gold). Huang Bai (Cortex Phellodendri) means 'yellow fir," and Jin Yin Hua (Flos Lonicerae) has the label 'golden silver flower."

Smell and taste

Unique flavors define specific names for some substances. Gan means 'sweet,' so Gan Cao (Radix glycyrrhizae) is 'sweet herb," an adequate description for the licorice root. "Ku" means bitter, thus Ku Shen (Sophorae flavescentis) translates as 'bitter herb.'

Geographic location

The locations or provinces in which herbs are grown often figure into herb names. For example, Bei Sha Shen (Radix glehniae) is grown and harvested in northern China, whereas Nan Sha Shen (Radix adenophorae) originated in southern China. And the Chinese words for north and south are respectively bei and nan.

Chuan Bei Mu (Bulbus fritillariae cirrhosae) and Chuan Niu Xi (Radix cyathulae) are both found in Sichuan province, as the character "chuan" indicates in their names.

Function

Some herbs, like Fang Feng (Radix Saposhnikoviae), literally 'prevent wind," prevents or treats wind-related illnesses. Xu Duan (Radix Dipsaci), literally 'restore the broken,' effectively treats torn soft tissues and broken bones.

Country of origin

Many herbs indigenous to other countries have been incorporated into the Chinese materia medica. Xi Yang Shen (Radix panacis quinquefolii), imported from North American crops, translates as 'western ginseng," while Dong Yang Shen (Radix ginseng Japonica), grown in and imported from North Asian countries, is 'eastern ginseng.'

Toxicity

From the earliest records regarding the use of medicinals to today, the toxicity of certain substances has been described in all Chinese materia medica. Since TCM has become more popular in the Western world, there are increasing concerns about the potential toxicity of many traditional Chinese medicinals including plants, animal parts and minerals. For most medicinals, efficacy and toxicity testing are based on traditional knowledge rather than laboratory analysis. The toxicity in some cases could be confirmed by modern research (i.e., in scorpion); in some cases it could not (i.e., in Curculigo). Further, ingredients may have different names in different locales or in historical texts, and different preparations may have similar names for the same reason, which can create inconsistencies and confusion in the creation of medicinals, with the possible danger of poisoning. Edzard Ernst "concluded that adverse effects of herbal medicines are an important albeit neglected subject in dermatology, which deserves further systematic investigation." Research suggests that the toxic heavy metals and undeclared drugs found in Chinese herbal medicines might be a serious health issue.

Substances known to be potentially dangerous include aconite, secretions from the Asiatic toad, powdered centipede, the Chinese beetle (Mylabris phalerata, Ban mao), and certain fungi. There are health problems associated with Aristolochia. Toxic effects are also frequent with Aconitum. To avoid its toxic adverse effects Xanthium sibiricum must be processed. Hepatotoxicity has been reported with products containing Reynoutria multiflora (synonym Polygonum multiflorum), glycyrrhizin, Senecio and Symphytum. The evidence suggests that hepatotoxic herbs also include Dictamnus dasycarpus, Astragalus membranaceous, and Paeonia lactiflora; although there is no evidence that they cause liver damage. Contrary to popular belief, Ganoderma lucidum mushroom extract, as an adjuvant for cancer immunotherapy, appears to have the potential for toxicity.

Also, adulteration of some herbal medicine preparations with conventional drugs which may cause serious adverse effects, such as corticosteroids, phenylbutazone, phenytoin, and glibenclamide, has been reported.

However, many adverse reactions are due to misuse or abuse of Chinese medicine. For example, the misuse of the dietary supplement Ephedra (containing ephedrine) can lead to adverse events including gastrointestinal problems as well as sudden death from cardiomyopathy. Products adulterated with pharmaceuticals for weight loss or erectile dysfunction are one of the main concerns. Chinese herbal medicine has been a major cause of acute liver failure in China.

Most Chinese herbs are safe but some have shown not to be. Reports have shown products being contaminated with drugs, toxins, or false reporting of ingredients. Some herbs used in TCM may also react with drugs, have side effects, or be dangerous to people with certain medical conditions.

Efficacy

Only a few trials exist that are considered to have adequate methodology by scientific standards. Proof of effectiveness is poorly documented or absent. A 2016 Cochrane review found "insufficient evidence that Chinese Herbal Medicines were any more or less effective than placebo or Hormonal Therapy" for the relief of menopause related symptoms. A 2012 Cochrane review found no difference in decreased mortality for SARS patients when Chinese herbs were used alongside Western medicine versus Western medicine exclusively. A 2010 Cochrane review found there is not enough robust evidence to support the effectiveness of traditional Chinese medicine herbs to stop the bleeding from haemorrhoids. A 2008 Cochrane review found promising evidence for the use of Chinese herbal medicine in relieving painful menstruation, compared to conventional medicine such as NSAIDs and the oral contraceptive pill, but the findings are of low methodological quality. A 2012 Cochrane review found weak evidence suggesting that some Chinese medicinal herbs have a similar effect at preventing and treating influenza as antiviral medication. Due to the poor quality of these medical studies, there is insufficient evidence to support or dismiss the use of Chinese medicinal herbs for the treatment of influenza. There is a need for larger and higher quality randomized clinical trials to determine how effective Chinese herbal medicine is for treating people with influenza. A 2005 Cochrane review found that although the evidence was weak for the use of any single herb, there was low quality evidence that some Chinese medicinal herbs may be effective for the treatment of acute pancreatitis.

Successful results have been scarce: artemisinin is one of few examples, as effective treatment for malaria derived from Artemisia annua, which is traditionally used to treat fever. Chinese herbology is largely pseudoscience, with no valid mechanism of action for the majority of its treatments.

Ecological impacts

The traditional practice of using (by now) endangered species is controversial within TCM. Modern Materia Medicas such as Bensky, Clavey and Stoger's comprehensive Chinese herbal text discuss substances derived from endangered species in an appendix, emphasizing alternatives.

Parts of endangered species used as TCM drugs include tiger bones and rhinoceros horn. Poachers supply the black market with such substances, and the black market in rhinoceros horn, for example, has reduced the world's rhino population by more than 90 percent over the past 40 years. Concerns have also arisen over the use of turtle plastron and seahorses.

TCM recognizes bear bile as a medicinal. In 1988, the Chinese Ministry of Health started controlling bile production, which previously used bears killed before winter. Now bears are fitted with a sort of permanent catheter, which is more profitable than killing the bears. More than 12,000 asiatic black bears are held in "bear farms", where they suffer cruel conditions while being held in tiny cages. The catheter leads through a permanent hole in the abdomen directly to the gall bladder, which can cause severe pain. Increased international attention has mostly stopped the use of bile outside of China; gallbladders from butchered cattle (牛胆; 牛膽; niú dǎn) are recommended as a substitute for this ingredient.

Collecting American ginseng to assist the Asian traditional medicine trade has made ginseng the most harvested wild plant in North America for the last two centuries, which eventually led to a listing on CITES Appendix II.

Herbs in use

Chinese herbology is a pseudoscientific practice with potentially unreliable product quality, safety hazards or misleading health advice. There are regulatory bodies, such as China GMP (Good Manufacturing Process) of herbal products. However, there have been notable cases of an absence of quality control during herbal product preparation. There is a lack of high-quality scientific research on herbology practices and product effectiveness for anti-disease activity. In the herbal sources listed below, there is little or no evidence for efficacy or proof of safety across consumer age groups and disease conditions for which they are intended.

There are over 300 herbs in common use. Some of the most commonly used herbs are Ginseng (人参; 人參; rénshēn), wolfberry (枸杞子; gǒuqǐzǐ), dong quai (Angelica sinensis, 当归; 當歸; dāngguī), astragalus (黄耆; 黃耆; huángqí), atractylodes (白术; 白朮; báizhú), bupleurum (柴胡; cháihú), cinnamon (cinnamon twigs (桂枝; guìzhī) and cinnamon bark (肉桂; ròuguì)), coptis (黄连; 黃連; huánglián), ginger (姜; 薑; jiāng), hoelen (茯苓; fúlíng), licorice (甘草; gāncǎo), ephedra sinica (麻黄; 麻黃; máhuáng), peony (white: 白芍; báisháo and reddish: 赤芍; chìsháo), rehmannia (地黄; 地黃; dìhuáng), rhubarb (大黄; 大黃; dàhuáng), and salvia (丹参; 丹參; dānshēn).

50 fundamental herbs

In Chinese herbology, there are 50 "fundamental" herbs, as given in the reference text, although these herbs are not universally recognized as such in other texts. The herbs are:

| Binomial nomenclature | Chinese name | English common name (when available) |

|---|---|---|

| Agastache rugosa, Pogostemon cablin | huò xiāng (藿香) | Korean mint, Patchouli |

| Alangium chinense | bā jiǎo fēng (八角枫) | Chinese Alangium root |

| Anemone chinensis (syn. Pulsatilla chinensis) | bái tóu weng (白头翁) | Chinese anemone |

| Anisodus tanguticus | shān làng dàng (山莨菪) | (trans.) Mountain henbane |

| Ardisia japonica | zǐ jīn niú (紫金牛) | Marlberry |

| Aster tataricus | zǐ wǎn (紫菀) | Tatar aster, Tartar aster |

| Astragalus propinquus (syn. Astragalus membranaceus) | huáng qí (黄芪) or běi qí (北芪) | Mongolian milkvetch |

| Camellia sinensis | chá shù (茶树) or chá yè (茶叶) | Tea plant |

| Cannabis sativa | dà má (大麻) | Cannabis |

| Carthamus tinctorius | hóng huā (红花) | Safflower |

| Cinnamomum cassia | ròu gùi (肉桂) | Cassia, Chinese cinnamon |

| Cissampelos pareira | xí shēng téng (锡生藤) or (亞乎奴) | Velvet leaf |

| Coptis chinensis | duǎn è huáng lián (短萼黄连) | Chinese goldthread |

| Corydalis yanhusuo | yán hú suǒ (延胡索) | Chinese poppy of Yan Hu Sou |

| Croton tiglium | bā dòu (巴豆) | Purging croton |

| Daphne genkwa | yuán huā (芫花) | Lilac daphne |

| Datura metel | yáng jīn huā (洋金花) | Devil's trumpet |

| Datura stramonium | zǐ huā màn tuó luó (紫花曼陀萝) | Jimson weed |

| Dendrobium nobile | shí hú (石斛) or shí hú lán (石斛兰) | Noble dendrobium |

| Dichroa febrifuga | cháng shān (常山) | Blue evergreen hydrangea, Chinese quinine |

| Ephedra sinica | cǎo má huáng (草麻黄) | Chinese ephedra |

| Eucommia ulmoides | dù zhòng (杜仲) | Hardy rubber tree |

| Euphorbia pekinensis | dà jǐ (大戟) | Peking spurge |

| Flueggea suffruticosa (formerly Securinega suffruticosa) | yī yè qiū (一叶秋) | |

| Forsythia suspensa | liánqiáo (连翘) | Weeping forsythia |

| Gentiana loureiroi | dì dīng (地丁) | |

| Gleditsia sinensis | zào jiá (皂荚) | Chinese honeylocust |

| Glycyrrhiza uralensis | gān cǎo (甘草) | Licorice |

| Hydnocarpus anthelminticus (syn. H. anthelminthica) | dà fēng zǐ (大风子) | Chaulmoogra tree |

| Ilex purpurea | dōngqīng (冬青) | Purple holly |

| Leonurus japonicus | yì mǔ cǎo (益母草) | Chinese motherwort |

| Ligusticum wallichii | chuān xiōng (川芎) | Szechwan lovage |

| Lobelia chinensis | bàn biān lián (半边莲) | Creeping lobelia |

| Phellodendron amurense | huáng bǎi (黄柏) | Amur cork tree |

| Platycladus orientalis (formerly Thuja orientalis) | cè bǎi (侧柏) | Chinese arborvitae |

| Pseudolarix amabilis | jīn qián sōng (金钱松) | Golden larch |

| Psilopeganum sinense | shān má huáng (山麻黄) | Naked rue |

| Pueraria lobata | gé gēn (葛根) | Kudzu |

| Rauvolfia serpentina | shégēnmù (蛇根木), cóng shégēnmù (從蛇根木) or yìndù shé mù (印度蛇木) | Sarpagandha, Indian snakeroot |

| Rehmannia glutinosa | dìhuáng (地黄) | Chinese foxglove |

| Rheum officinale | yào yòng dà huáng (药用大黄) | Chinese or Eastern rhubarb |

| Rhododendron qinghaiense | Qīng hǎi dù juān (青海杜鹃) | |

| Saussurea costus | yún mù xiāng (云木香) | Costus root |

| Schisandra chinensis | wǔ wèi zi (五味子) | Chinese magnolia vine |

| Scutellaria baicalensis | huáng qín (黄芩) | Baikal skullcap |

| Stemona tuberosa | bǎi bù (百部) | |

| Stephania tetrandra | fáng jǐ (防己) | Stephania root |

| Styphnolobium japonicum (formerly Sophora japonica) | huái (槐), huái shù (槐树), or huái huā (槐花) | Pagoda tree |

| Trichosanthes kirilowii | guā lóu (栝楼) | Chinese cucumber |

| Wikstroemia indica | liāo gē wáng (了哥王) | Indian stringbush |

Other Chinese herbs

In addition to the above, many other Chinese herbs and other substances are in common use, and these include:

- Akebia quinata (木通)

- Arisaema heterophyllum (胆南星)

- Chenpi (sun-dried tangerine (mandarin) peel) (陳皮)

- Clematis (威灵仙)

- Concretio silicea bambusae (天竺黄)

- Cordyceps sinensis (冬虫夏草)

- Curcuma (郁金)

- Dalbergia odorifera (降香)

- Myrrh (没药)

- Frankincense (乳香)

- Persicaria (桃仁)

- Patchouli' (广藿香)

- Polygonum (虎杖)

- Sparganium (三棱)

- Zedoary (Curcuma zedoaria) (莪朮)

See also

- Chinese classic herbal formula

- Chinese ophthalmology

- Compendium of Materia Medica

- Hallucinogenic plants in Chinese herbals

- Herbalism, for the use of medicinal herbs in other traditions.

- Japanese star anise

- Jiuhuang Bencao

- Kampo (traditional Japanese medicine)

- Li Shizhen

- Pharmacognosy

- Star anise

- Traditional Chinese medicine

- Traditional Korean medicine

- Traditional Vietnamese medicine

- Yaoxing Lun

References

- Chen, John K.; Chen, Tina T. (2004). Chinese Medical Herbology and Pharmacology. ISBN 0-9740635-0-9.

- Chen, John K.; Chen, Tina T. (2009). Pocket Atlas of Chinese Medicine. ISBN 978-0-9740635-7-7.

- Ergil, M.; et al. (2009). Pocket Atlas of Chinese Medicine. Thieme. ISBN 978-3-13-141611-7.

- Foster, S.; Yue, C. (1992). Herbal emissaries: bringing Chinese herbs to the West. Healing Arts Press. ISBN 978-0-89281-349-0.

- Kiessler, Malte (2005). Traditionelle Chinesische Innere Medizin (in German). Elsevier, Urban & Fischer. ISBN 978-3-437-57220-3.

- Goldschmidt, Asaf (2009). The Evolution of Chinese Medicine: Song Dynasty, 960-1200. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-42655-8.

- Sivin, Nathan (1987). Traditional Medicine in Contemporary China. Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies, University of Michigan. ISBN 978-0-89264-074-4.

- Unschuld, Paul U. (1985). Medicine in China: A History of Ideas. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05023-5.

- Xu, L.; Wang, W. (2002). Chinese materia medica: combinations and applications (1st ed.). Donica Publishing. ISBN 978-1-901149-02-9.

External links

Quotations related to Traditional Chinese medicine at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Traditional Chinese medicine at Wikiquote