タンパク質 (栄養素)

Protein (nutrient)/ja

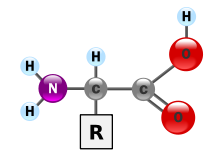

タンパク質は、人体にとって不可欠な栄養素である。体組織の構成要素の一つであり、燃料源としても機能する。燃料として、タンパク質は炭水化物と同じくらいのエネルギー密度を提供する: 1グラムあたり4kcal(17kJ)であるのに対し、脂質は1グラムあたり9kcal(37kJ)である。 栄養学的見地から見たタンパク質の最も重要な側面と特徴は、そのアミノ酸組成である。

タンパク質はアミノ酸がペプチド結合で結合したポリマー鎖である。ヒトの消化の際、タンパク質は胃の中で塩酸とプロテアーゼの作用によってより小さなポリペプチド鎖に分解される。これは、体内で生合成できない必須アミノ酸を吸収するために極めて重要である。

タンパク質-エネルギー栄養失調とその結果としての死を防ぐために、人間が食事から摂取しなければならない9つの必須アミノ酸がある。それらはフェニルアラニン、バリン、スレオニン、トリプトファン、メチオニン、ロイシン、イソロイシン、リジン、ヒスチジンである。必須アミノ酸が8種類か9種類かについては議論がある。ヒスチジンは成人では合成されないため、コンセンサスは9に傾いているようだ。人間が体内で合成できるアミノ酸は5つある。アラニン、アスパラギン酸、アスパラギン、グルタミン酸、セリンである。乳幼児の未熟児や重度の異化不全にある人など、特殊な病態生理学的条件下で合成が制限される6種類の条件付き必須アミノ酸がある。これらの6つはアルギニン、システイン、グリシン、グルタミン、プロリン、チロシンである。タンパク質の食事源としては、穀物、豆類、種子類が挙げられる、

人体におけるタンパク質の働き

タンパク質は人体の成長と維持に必要な栄養素である。水を除けば、タンパク質は体内で最も豊富な種類の分子である。タンパク質は全身の細胞に存在し、特に筋肉の主要な構造成分である。これには身体の臓器、毛髪、皮膚も含まれる。タンパク質は糖タンパク質などの膜にも使われる。アミノ酸に分解されると、核酸、補酵素、ホルモン、免疫反応、細胞修復、その他生命維持に不可欠な分子の前駆体として使われる。さらに、タンパク質は血液細胞を形成するためにも必要である。

摂取源

| カテゴリ | 畜産物の貢献 [%] |

|---|---|

| カロリー | 18

|

| タンパク質 | 37

|

| 土地利用 | 83

|

| 温室効果ガス | 58

|

| 水汚染 | 57

|

| 空気汚染 | 56

|

| 淡水取水量 | 33

|

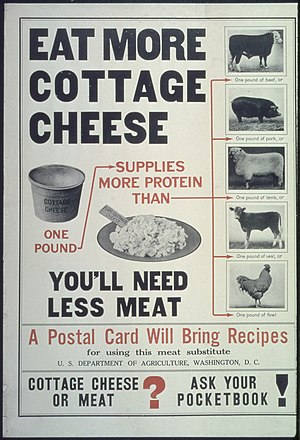

タンパク質は様々な食品に含まれている。世界的に見ると、植物性タンパク質食品は一人当たりのタンパク質供給量の60%以上を占めている。北米では、動物由来の食品がタンパク質源の約70%を占めている。昆虫は世界の多くの地域でタンパク源となっている。アフリカの一部では、食事性タンパク質の最大50%が昆虫由来である。毎日20億人以上の人が昆虫を食べていると推定されている。

肉、乳製品、卵、大豆、魚、全粒穀物、穀類がタンパク質源である。主食であり、7%以上の濃度を持つ穀類のタンパク源としては、ソバ、オート麦、ライ麦、キビ、トウモロコシ、米、小麦、ソルガムきび、アマランサス、キヌアなどがある(順不同)。タンパク質源としてジビエ肉に注目する研究もある。

植物性タンパク源には、豆類、ナッツ類、種子類、穀類、一部の野菜や果物が含まれる。タンパク質濃度が7%を超える植物性食品には、大豆、レンズ豆、インゲン豆、白インゲン豆、緑豆、ひよこ豆、ササゲ、ライマメ、キマメ、ルピナス、手裏豆、アーモンド、ブラジルナッツ、カシューナッツ、ピーカン、クルミ、綿の実、カボチャの種、麻の実、ゴマ、ヒマワリの種などがある(ただし、これらに限定されない)。

太陽光発電を利用した微生物によるタンパク質生産は、ソーラーパネルからの電力と空気中の二酸化炭素を利用して微生物用の燃料を作り、バイオリアクター槽で増殖させ、乾燥したタンパク質粉末に加工する。このプロセスは、土地、水、肥料を非常に効率的に利用する。

バランスの取れた食事をしている人には、タンパク質サプリメントは必要ない。

下の表は、タンパク質源としての食品群を示している。

| Food source | Lysine/ja | Threonine/ja | Tryptophan/ja | 含硫 アミノ酸 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Legumes/ja | 64 | 38 | 12 | 25 |

| Cereals/jaとwhole grain/ja | 31 | 32 | 12 | 37 |

| ナッツとseed/ja | 45 | 36 | 17 | 46 |

| Fruit/ja | 45 | 29 | 11 | 27 |

| Animal/ja | 85 | 44 | 12 | 38 |

Colour key:

- 各アミノ酸の密度が最も高いタンパク質源

- 各アミノ酸の密度が最も低いタンパク質源

カゼイン、ホエイ、卵、米、大豆、コオロギ粉などのプロテインパウダーは、加工・製造されたタンパク源である。

食品中の検査

食品中のタンパク質濃度の古典的な測定法は、ケルダール法とデュマ法である。これらの検査は試料中の全窒素を測定する。ほとんどの食品で窒素を含む唯一の主要成分はタンパク質である(脂肪、炭水化物、食物繊維は窒素を含まない)。窒素の量に、食品に含まれるタンパク質の種類に応じた係数をかけると、総タンパク質が求められる。この値は「粗タンパク質」含有量として知られている。正しい換算係数の使用については、特に植物由来のタンパク質製品の導入に伴い、激しい議論が交わされている。しかし、食品表示上のタンパク質は、窒素に6.25を掛けた値で計算される。ケルダール法は、AOACインターナショナルが採用している方法であるため、世界中の多くの食品標準機関で使用されているが、デュマ法もいくつかの標準機関では承認されている。

Accidental contamination and intentional adulteration of protein meals with non-protein nitrogen sources that inflate crude protein content measurements have been known to occur in the food industry for decades. To ensure food quality, purchasers of protein meals routinely conduct quality control tests designed to detect the most common non-protein nitrogen contaminants, such as urea and ammonium nitrate.

In at least one segment of the food industry, the dairy industry, some countries (at least the U.S., Australia, France and Hungary) have adopted "true protein" measurement, as opposed to crude protein measurement, as the standard for payment and testing: "True protein is a measure of only the proteins in milk, whereas crude protein is a measure of all sources of nitrogen and includes nonprotein nitrogen, such as urea, which has no food value to humans. ... Current milk-testing equipment measures peptide bonds, a direct measure of true protein." Measuring peptide bonds in grains has also been put into practice in several countries including Canada, the UK, Australia, Russia and Argentina where near-infrared reflectance (NIR) technology, a type of infrared spectroscopy is used. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) recommends that only amino acid analysis be used to determine protein in, inter alia, foods used as the sole source of nourishment, such as infant formula, but also provides: "When data on amino acids analyses are not available, determination of protein based on total N content by Kjeldahl (AOAC, 2000) or similar method ... is considered acceptable."

The testing method for protein in beef cattle feed has grown into a science over the post-war years. The standard text in the United States, Nutrient Requirements of Beef Cattle, has been through eight editions over at least seventy years. The 1996 sixth edition substituted for the fifth edition's crude protein the concept of "metabolizeable protein", which was defined around the year 2000 as "the true protein absorbed by the intestine, supplied by microbial protein and undegraded intake protein".

The limitations of the Kjeldahl method were at the heart of the Chinese protein export contamination in 2007 and the 2008 China milk scandal in which the industrial chemical melamine was added to the milk or glutens to increase the measured "protein".

Protein quality

The most important aspect and defining characteristic of protein from a nutritional standpoint is its amino acid composition. There are multiple systems which rate proteins by their usefulness to an organism based on their relative percentage of amino acids and, in some systems, the digestibility of the protein source. They include biological value, net protein utilization, and PDCAAS (Protein Digestibility Corrected Amino Acids Score) which was developed by the FDA as a modification of the Protein efficiency ratio (PER) method. The PDCAAS rating was adopted by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations/World Health Organization (FAO/WHO) in 1993 as "the preferred 'best'" method to determine protein quality. These organizations have suggested that other methods for evaluating the quality of protein are inferior. In 2013 FAO proposed changing to Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score.

Digestion

Most proteins are decomposed to single amino acids by digestion in the gastro-intestinal tract.

Digestion typically begins in the stomach when pepsinogen is converted to pepsin by the action of hydrochloric acid, and continued by trypsin and chymotrypsin in the small intestine. Before the absorption in the small intestine, most proteins are already reduced to single amino acid or peptides of several amino acids. Most peptides longer than four amino acids are not absorbed. Absorption into the intestinal absorptive cells is not the end. There, most of the peptides are broken into single amino acids.

Absorption of the amino acids and their derivatives into which dietary protein is degraded is done by the gastrointestinal tract. The absorption rates of individual amino acids are highly dependent on the protein source; for example, the digestibilities of many amino acids in humans, the difference between soy and milk proteins and between individual milk proteins, beta-lactoglobulin and casein. For milk proteins, about 50% of the ingested protein is absorbed between the stomach and the jejunum and 90% is absorbed by the time the digested food reaches the ileum. Biological value (BV) is a measure of the proportion of absorbed protein from a food which becomes incorporated into the proteins of the organism's body.

Newborn

Newborns of mammals are exceptional in protein digestion and assimilation in that they can absorb intact proteins at the small intestine. This enables passive immunity, i.e., transfer of immunoglobulins from the mother to the newborn, via milk.

Dietary requirements

Considerable debate has taken place regarding issues surrounding protein intake requirements. The amount of protein required in a person's diet is determined in large part by overall energy intake, the body's need for nitrogen and essential amino acids, body weight and composition, rate of growth in the individual, physical activity level, the individual's energy and carbohydrate intake, and the presence of illness or injury. Physical activity and exertion as well as enhanced muscular mass increase the need for protein. Requirements are also greater during childhood for growth and development, during pregnancy, or when breastfeeding in order to nourish a baby or when the body needs to recover from malnutrition or trauma or after an operation.

Dietary recommendations

According to US & Canadian Dietary Reference Intake guidelines, women aged 19–70 need to consume 46 grams of protein per day while men aged 19–70 need to consume 56 grams of protein per day to minimize risk of deficiency. These Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) were calculated based on 0.8 grams protein per kilogram body weight and average body weights of 57 kg (126 pounds) and 70 kg (154 pounds), respectively. However, this recommendation is based on structural requirements but disregards use of protein for energy metabolism. This requirement is for a normal sedentary person. In the United States, average protein consumption is higher than the RDA. According to results of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES 2013–2014), average protein consumption for women ages 20 and older was 69.8 grams and for men 98.3 grams/day.

Active people

Several studies have concluded that active people and athletes may require elevated protein intake (compared to 0.8 g/kg) due to increase in muscle mass and sweat losses, as well as need for body repair and energy source. Suggested amounts vary from 1.2 to 1.4 g/kg for those doing endurance exercise to as much as 1.6-1.8 g/kg for strength exercise and up to 2.0 g/kg/day for older people, while a proposed maximum daily protein intake would be approximately 25% of energy requirements i.e. approximately 2 to 2.5 g/kg. However, many questions still remain to be resolved.

In addition, some have suggested that athletes using restricted-calorie diets for weight loss should further increase their protein consumption, possibly to 1.8–2.0 g/kg, in order to avoid loss of lean muscle mass.

Aerobic exercise protein needs

Endurance athletes differ from strength-building athletes in that endurance athletes do not build as much muscle mass from training as strength-building athletes do. Research suggests that individuals performing endurance activity require more protein intake than sedentary individuals so that muscles broken down during endurance workouts can be repaired. Although the protein requirement for athletes still remains controversial (for instance see Lamont, Nutrition Research Reviews, pages 142 - 149, 2012), research does show that endurance athletes can benefit from increasing protein intake because the type of exercise endurance athletes participate in still alters the protein metabolism pathway. The overall protein requirement increases because of amino acid oxidation in endurance-trained athletes. Endurance athletes who exercise over a long period (2–5 hours per training session) use protein as a source of 5–10% of their total energy expended. Therefore, a slight increase in protein intake may be beneficial to endurance athletes by replacing the protein lost in energy expenditure and protein lost in repairing muscles. One review concluded that endurance athletes may increase daily protein intake to a maximum of 1.2–1.4 g per kg body weight.

Anaerobic exercise protein needs

Research also indicates that individuals performing strength training activity require more protein than sedentary individuals. Strength-training athletes may increase their daily protein intake to a maximum of 1.4–1.8 g per kg body weight to enhance muscle protein synthesis, or to make up for the loss of amino acid oxidation during exercise. Many athletes maintain a high-protein diet as part of their training. In fact, some athletes who specialize in anaerobic sports (e.g., weightlifting) believe a very high level of protein intake is necessary, and so consume high protein meals and also protein supplements.

Special populations

Protein allergies

A food allergy is an abnormal immune response to proteins in food. The signs and symptoms may range from mild to severe. They may include itchiness, swelling of the tongue, vomiting, diarrhea, hives, trouble breathing, or low blood pressure. These symptoms typically occurs within minutes to one hour after exposure. When the symptoms are severe, it is known as anaphylaxis. The following eight foods are responsible for about 90% of allergic reactions: cow's milk, eggs, wheat, shellfish, fish, peanuts, tree nuts and soy.

Chronic kidney disease

While there is no conclusive evidence that a high protein diet can cause chronic kidney disease, there is a consensus that people with this disease should decrease consumption of protein. According to one 2009 review updated in 2018, people with chronic kidney disease who reduce protein consumption have less likelihood of progressing to end stage kidney disease. Moreover, people with this disease while using a low protein diet (0.6 g/kg/d - 0.8 g/kg/d) may develop metabolic compensations that preserve kidney function, although in some people, malnutrition may occur.

Phenylketonuria

Individuals with phenylketonuria (PKU) must keep their intake of phenylalanine – an essential amino acid – extremely low to prevent a mental disability and other metabolic complications. Phenylalanine is a component of the artificial sweetener aspartame, so people with PKU need to avoid low calorie beverages and foods with this ingredient.

過剰消費

米国とカナダにおけるタンパク質の食事摂取基準に関する検討では、耐容上限摂取量、すなわちタンパク質を安全に摂取できる量の上限を設定するには十分な証拠がないと結論づけられた。

アミノ酸が必要量を超えると、肝臓はアミノ酸を取り込み、脱アミノ化する。この過程でアミノ酸の窒素はアンモニアに変換され、さらに肝臓で尿素サイクルを介して尿素に処理される。尿素の排泄は腎臓を介して行われる。アミノ酸分子の他の部分はグルコースに変換され、燃料として利用される。食物のタンパク質摂取量が周期的に多かったり少なかったりする場合、身体は「不安定なタンパク質予備軍」を使ってタンパク質摂取量の日々の変動を補うことで、タンパク質レベルを平衡に保とうとする。しかし、将来必要となるカロリーの予備としての体脂肪とは異なり、将来必要となるタンパク質の貯蔵はない。

タンパク質の過剰摂取は、硫黄アミノ酸の酸化によるpHの不均衡を補うために起こり、尿中のカルシウム排泄を増加させる可能性がある。このため、腎循環系内のカルシウムから腎結石が形成されるリスクが高くなる可能性がある。あるメタアナリシスでは、高タンパク質摂取による骨密度への悪影響はないと報告している。別のメタアナリシスでは、動物性タンパク質と植物性タンパク質の間に差はないが、タンパク質の多い食事によって収縮期血圧と拡張期血圧がわずかに低下することが報告されている。

高タンパク質食は、メタアナリシスにおいて、ベースラインのタンパク質食と比較して、3ヶ月間でさらに1.21 kgの体重減少につながることが示されている。BMIの低下やHDLコレステロールの減少という利益は、高タンパク質摂取量が総エネルギー摂取量の45%と分類された研究よりも、むしろタンパク質摂取量がわずかに増加した研究において、より強く観察された。心血管系の活動に対する有害な影響は、6ヵ月以下の短期間の食事では観察されなかった。長期的な高タンパク質食が健康な個人に及ぼす潜在的な有害影響については、ほとんどコンセンサスが得られていないため、高タンパク質摂取を減量の一形態として使用することについては注意が必要である。

2015-2020年版アメリカ人のための食事摂取基準(DGA)は、男性および10代の少年に対し、果物、野菜、その他摂取量の少ない食品の摂取量を増やすよう推奨しており、そのための手段として、タンパク質食品の摂取量を全体的に減らすことを挙げている。2015〜2020年のDGA報告書では、赤身肉と加工肉の推奨摂取量は設定されていない。報告書は、赤肉や加工肉の摂取量の減少が成人の心血管系疾患のリスク低下と相関していることを示す研究を認める一方で、これらの肉から得られる栄養素の価値にも言及している。推奨されているのは、肉やタンパク質の摂取を制限することではなく、特定の肉やタンパク質の摂取によって増加する可能性のあるナトリウム(2300 mg未満)、飽和脂肪(1日あたりの総カロリーの10%未満)、加糖(1日あたりの総カロリーの10%未満)を監視し、1日の制限値内に抑えることである。2015年のDGA報告書では、赤身肉や加工肉の摂取量を減らすよう勧告しているが、2015-2020年のDGA主要勧告では、ベジタリアンおよび非ベジタリアンの両方のタンパク源を含む、様々なタンパク質食品を摂取するよう勧告している。

タンパク質欠乏症

タンパク質欠乏・栄養不良(PEM)は、知的障害やクワシオルコルを含む様々な病気を引き起こす可能性がある。クワシオルコルの症状には、無気力、下痢、不活発、成長不全、皮膚のかさつき、脂肪肝、腹と脚の浮腫などがある。この浮腫は、リポキシゲナーゼがアラキドン酸に作用してロイコトリエンを形成することと、体液バランスおよびリポ蛋白輸送における蛋白質の正常な機能によって説明される。

PEMは小児、成人ともに世界的にかなり多くみられ、年間600万人が死亡している。先進工業国では、PEMは主に病院でみられ、疾患と関連しているか、高齢者に多くみられる。