ボディマス指数

Body mass index/ja

| ボディマス指数 (BMI) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Synonyms | Quetelet index |

| MeSH | D015992 |

| MedlinePlus | 007196 |

| LOINC | 39156-5 |

| aシリーズの一部である。 |

| 体重 |

|---|

ボディマス指数(BMI)は、人の質量(体重)と身長から導き出される値である。BMIは、体重を身長の2乗で割ったものとして定義され、kg/m2の単位で表される。質量はキログラム(kg)、身長はメートル(m)である。

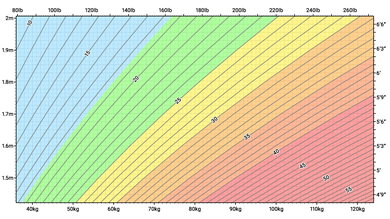

BMIは、まず体重計とスタジオメーターを用いてその構成要素を測定することによって決定することができる。掛け算と割り算は、手書きまたは電卓を使って直接行うこともできるし、ルックアップテーブル(またはチャート)を使って間接的に行うこともできる。表はBMIを質量と身長の関数として表示し、他の測定単位(計算のためにメートル単位に変換)を表示することができる。また、BMIのカテゴリーごとに等高線や色を表示することもできる。

BMIは、組織量(筋肉、脂肪、骨)と身長に基づいて人を大まかに分類するために用いられる便利な経験則である。成人の主なBMI分類は、低体重(18.5kg/m2未満)、標準体重(18.5~24.9)、過体重(25~29.9)、肥満(30以上)である。 集団の統計的測定値としてではなく、個人の健康状態を予測するために使用する場合、BMIには制限があり、特に腹部肥満、低身長、高筋肉量の個人に適用する場合、いくつかの代替のものよりも有用性が低くなることがある。

BMIが20未満でも25以上でも全死亡率が高く、20-25の範囲から離れるほどリスクは高くなる。

歴史

ベルギーの天文学者、数学者、統計学者、社会学者であるアドルフ・ケテレは、彼が「社会物理学」と呼ぶものを開発する中で、1830年から1850年の間にBMIの基礎を考案した。ケテレ自身は、当時ケテレ指数と呼ばれていたこの指数を、医学的評価の手段として使用するつもりはなかった。その代わり、この指数は彼のl'homme moyen(平均的人間)研究の一要素であった。ケテレは平均的な人間を社会的理想と考え、社会的に理想的な人間を発見する手段として肥満度を開発した。『Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research』誌のLars GrueとArvid Heibergによれば、ケテレの平均的人間の理想化は、10年後の優生学の発展において、フランシス・ガルトンによってさらに精緻化されることになる。

身長の2乗に対する人間の体重の比率を表す「体格指数」(BMI)という現代用語は、アンセル・キーズらによって1972年7月号の慢性疾患ジャーナルに発表された論文で作られた。この論文でキーズは、BMIと呼ばれるものが「完全に満足できるものではないにしても、少なくとも相対的な肥満の指標としては他の相対的な体重指数と同じくらい優れている」と主張した。

体脂肪を測定する指標への関心は、豊かな西欧社会で肥満が増加していることが観察されたことから生まれた。キーズは、BMIは集団の研究に適しており、個人の評価には不適切であると明確に判断した。それにもかかわらず、その単純さゆえに、予備診断に広く使われるようになった。ウエスト周囲径のような付加的な指標はより有用である。

BMIはkg/m2で表され、質量はキログラム、身長はメートルである。ポンドとインチを使う場合、換算係数は703 となる(kg/m2)/(lb/in2)。 (ポンドとフィートを使用する場合は、4.88の換算係数が使用される) BMIという用語が非公式に使用される場合、単位は通常省略される。

BMIは、人の太さまたはやせ具合を数値で簡単に表すことができるため、医療専門家が体重の問題を患者とより客観的に話し合うことができる。BMIは、平均的な体組成を持つ平均的な座りがちな(身体的に不活発な)集団を分類する単純な手段として使用するように設計された。そのような人々に対して、BMI値の推奨2014年現在は以下の通り: 18.5~24.9 kg/m2は最適体重、18.5未満は低体重、25~29.9は過体重、30以上は肥満を示す。痩せている男性アスリートは筋肉と脂肪の比率が高いことが多く、そのためBMIは体脂肪率に対して誤解を招くほど高くなる。

カテゴリー

BMIの一般的な使用法は、個人の体重がその人の身長の標準値からどの程度ずれているかを評価することである。体重の過不足は、部分的には体脂肪(脂肪組織)によって説明されるかもしれないが、筋肉質などの他の要因もBMIに大きく影響する(以下の議論および過体重を参照)。

WHOは、成人のBMIが18.5未満を低体重とみなし、栄養失調、摂食障害、またはその他の健康問題を示している可能性があるとし、BMIが25以上を過体重、30以上を肥満とみなしている。原則的で国際的なWHOのBMIカットオフポイント(16、17、18.5、25、30、35、40)に加えて、リスクのあるアジア人に対する4つのカットオフポイント(23、27.5、32.5、37.5)が特定された。これらのBMI値の範囲は、統計上のカテゴリーとしてのみ有効である。

| カテゴリ | BMI (kg/m2) | BMIプライム |

|---|---|---|

| 低体重(重度のやせ) | < 16.0 | < 0.64 |

| 低体重(中程度のやせ) | 16.0 – 16.9 | 0.64 – 0.67 |

| 低体重(軽度のやせ) | 17.0 – 18.4 | 0.68 – 0.73 |

| 正常範囲 | 18.5 – 24.9 | 0.74 – 0.99 |

| 過体重(肥満予備軍) | 25.0 – 29.9 | 1.00 – 1.19 |

| 肥満 (Class I) | 30.0 – 34.9 | 1.20 – 1.39 |

| 肥満 (Class II) | 35.0 – 39.9 | 1.40 – 1.59 |

| 肥満 (Class III) | ≥ 40.0 | ≥ 1.60 |

子供と青少年

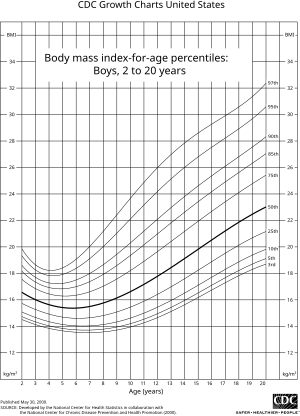

BMIは、2歳から20歳までで使用方法が異なる。BMIは成人と同じ方法で計算されるが、同じ年齢の他の子供や青少年の典型的な値と比較される。低体重と過体重の固定された基準値との比較の代わりに、BMIは同じ性別と年齢の子どものパーセンタイル値と比較される。

BMIが5パーセンタイル未満は低体重、95パーセンタイル以上は肥満とみなされる。BMIが85パーセンタイルと95パーセンタイルの間の子どもは過体重とみなされる。 2013年にイギリスで行われた調査では、12歳から16歳までの女性のBMIは、同年齢の男性よりも平均で1.0 kg/m2高かった。

国際的な差異

直線的な尺度に沿って推奨されるこれらの区別は、時代や国によって異なる可能性があり、世界的な縦断的調査を問題にしている。BMI、体脂肪率と健康リスクとの関連は、異なる集団や血統の人々によって異なっており、2型糖尿病やアテローム性動脈硬化症の心血管疾患のリスクは、WHOの過体重のカットオフポイントである25 kg/m2より低いBMIで高くなるが、観察されるリスクのカットオフは集団によって異なる。観察されたリスクのカットオフ値は、ヨーロッパ、アジア、アフリカの集団や小集団によって異なる。

====香港 香港の病院局は以下のBMI範囲の使用を推奨している:

| カテゴリ | BMI (kg/m2) |

|---|---|

| 低体重(不健康) | < 18.5 |

| 正常範囲(健康) | 18.5 – 22.9 |

| 過体重Ⅰ(リスクあり) | 23.0 – 24.9 |

| 過体重II(中等度肥満) | 25.0 – 29.9 |

| 過体重III(高度肥満) | ≥ 30.0 |

日本

日本肥満学会(JASSO)の2000年の研究によると、BMIの分類は以下のようになっている:

| カテゴリ | BMI (kg/m2) |

|---|---|

| 低体重(痩せ型) | < 18.5 |

| 標準体重 | 18.5 – 24.9 |

| 肥満(クラス1) | 25.0 – 29.9 |

| 肥満(クラス2) | 30.0 – 34.9 |

| 肥満(クラス3) | 35.0 – 39.9 |

| 肥満(クラス4) | ≥ 40.0 |

シンガポール

シンガポールでは、2005年に健康増進委員会(HPB)によってBMIカットオフ値が改訂された。これは、シンガポール人を含む多くのアジア人集団は、他国の一般的なBMI推奨値と比較して体脂肪の割合が高く、心血管疾患や糖尿病のリスクが高いという研究結果を受けたものである。BMIカットオフ値は、体重よりもむしろ健康リスクに重点を置いて提示されている。

| カテゴリ | BMI (kg/m2) | 健康リスク |

|---|---|---|

| 低体重 | < 18.5 | 栄養不足と骨粗鬆症の可能性がある。 |

| 正常 | 18.5 – 22.9 | リスクが低い(健康な範囲)。 |

| 軽度から中等度の過体重 | 23.0 – 27.4 | 心臓病、高血圧、脳卒中、糖尿病の発症リスクは中程度である。 |

| 非常に太りすぎ~肥満 | ≥ 27.5 | 心臓病、高血圧、脳卒中、糖尿病発症の高いリスク。代謝症候群。 |

イギリス

イギリスでは、NICEのガイダンスにより、2型糖尿病の予防はBMIが白人で30、アフリカ系黒人、アフリカ系カリブ人、南アジア人、中国人の集団では27.5から開始することが推奨されている。

イングランドの約150万人を対象とした大規模サンプルに基づく新たな調査によると、BMI(四捨五入)以上であれば予防の恩恵を受けられる民族グループがあることがわかった:

- 白人では30

- 黒人では28

- 英国系黒人では30をわずかに下回る

- アフリカ系黒人では29

- 黒人その他で27

- カリブ系黒人の26

- アラブ系および中国系では 27

- 南アジア系では24人

- パキスタン、インド、ネパール人で24人

- タミール人とスリランカ人で23人

- バングラデシュ人の21%である。

米国

1998年、米国国立衛生研究所は、米国の定義を世界保健機関のガイドラインに沿ったものにし、正常/過体重のカットオフをBMI 27.8(男性)および27.3(女性)からBMI 25に引き下げた。これにより、これまで健康であった約2,500万人のアメリカ人が太りすぎに再定義された。

このことは、過去20年間に太りすぎと診断されることが増加し、同時期に減量商品の売上が増加したことを部分的に説明することができる。また、WHOは、東南アジアの体型の標準/過体重の基準値をBMI23前後に引き下げることを推奨しており、さまざまな体型の臨床研究からさらなる改訂が出てくることを期待している。

2007年の調査では、アメリカ人の63%が過体重または肥満であり、26%が肥満(BMI30以上)であった。2014年には、米国の成人の37.7%が肥満で、男性は35.0%、女性は40.4%で、クラス3肥満(BMI40以上)の値は男性で7.7%、女性で9.9%だった。2015-2016年のアメリカ国民健康栄養調査によると、アメリカ人男女の71.6%がBMI25以上であった。肥満-BMI30以上-は米国成人の39.8%に見られた。

| 年齢 | パーセンテージ | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5th | 10th | 15th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 85th | 90th | 95th | |

| ≥ 20 (total) | 20.7 | 22.2 | 23.0 | 24.6 | 27.7 | 31.6 | 34.0 | 36.1 | 39.8 |

| 20–29 | 19.3 | 20.5 | 21.2 | 22.5 | 25.5 | 30.5 | 33.1 | 35.1 | 39.2 |

| 30–39 | 21.1 | 22.4 | 23.3 | 24.8 | 27.5 | 31.9 | 35.1 | 36.5 | 39.3 |

| 40–49 | 21.9 | 23.4 | 24.3 | 25.7 | 28.5 | 31.9 | 34.4 | 36.5 | 40.0 |

| 50–59 | 21.6 | 22.7 | 23.6 | 25.4 | 28.3 | 32.0 | 34.0 | 35.2 | 40.3 |

| 60–69 | 21.6 | 22.7 | 23.6 | 25.3 | 28.0 | 32.4 | 35.3 | 36.9 | 41.2 |

| 70–79 | 21.5 | 23.2 | 23.9 | 25.4 | 27.8 | 30.9 | 33.1 | 34.9 | 38.9 |

| ≥ 80 | 20.0 | 21.5 | 22.5 | 24.1 | 26.3 | 29.0 | 31.1 | 32.3 | 33.8 |

| 年齢 | パーセンテージ | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5th | 10th | 15th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 85th | 90th | 95th | |

| ≥ 20 (total) | 19.6 | 21.0 | 22.0 | 23.6 | 27.7 | 33.2 | 36.5 | 39.3 | 43.3 |

| 20–29 | 18.6 | 19.8 | 20.7 | 21.9 | 25.6 | 31.8 | 36.0 | 38.9 | 42.0 |

| 30–39 | 19.8 | 21.1 | 22.0 | 23.3 | 27.6 | 33.1 | 36.6 | 40.0 | 44.7 |

| 40–49 | 20.0 | 21.5 | 22.5 | 23.7 | 28.1 | 33.4 | 37.0 | 39.6 | 44.5 |

| 50–59 | 19.9 | 21.5 | 22.2 | 24.5 | 28.6 | 34.4 | 38.3 | 40.7 | 45.2 |

| 60–69 | 20.0 | 21.7 | 23.0 | 24.5 | 28.9 | 33.4 | 36.1 | 38.7 | 41.8 |

| 70–79 | 20.5 | 22.1 | 22.9 | 24.6 | 28.3 | 33.4 | 36.5 | 39.1 | 42.9 |

| ≥ 80 | 19.3 | 20.4 | 21.3 | 23.3 | 26.1 | 29.7 | 30.9 | 32.8 | 35.2 |

成人における高値の影響

BMIの範囲は、体重と疾病および死亡との関係に基づいている。過体重および肥満の人は、以下の疾患のリスクが高くなる:

タバコを吸ったことのない人では、体重が普通である人に比べて、過体重/肥満は死亡率を51%増加させる。

適用

公衆衛生

BMIは一般的に、一般的な質量で関連するグループ間の相関の手段として使用され、脂肪率を推定する漠然とした手段として機能することができる。BMIの二面性は、一般的な計算としては使いやすいが、そこから得られるデータがどの程度正確で適切なものであるかに限界があることである。一般に、BMIは誤差が少ないため、座りがちな人や太り過ぎの人の傾向を把握するのに適している。BMIは、WHOによって1980年代初頭以来、肥満統計を記録するための標準として使用されている。

この一般的な相関関係は、肥満やその他の様々な状態に関するコンセンサス・データとして特に有用である。というのも、このデータを使って半精密な表現を構築し、そこから解決策を規定したり、あるグループのRDAを計算したりできるからである。同様に、子どもたちの大半は座りがちであるため、これは子どもたちの成長にとってますます適切になってきている。 横断的研究では、座りがちな人がより身体的に活動的になることで、BMIを減少させることができることが示された。前向きコホート研究では、BMIのさらなる上昇を防ぐ手段として積極的な運動を支持するような、より小さな効果が見られる。

法律

フランス、イタリア、スペインでは、BMI18未満のファッションショーモデルの使用を禁止する法律が導入されている。イスラエルでは、BMI18.5未満のモデルは禁止されている。これはモデルやファッションに関心のある人々の拒食症と闘うために行われている。

健康との関係

2005年にJournal of the American Medical Association (JAMA)によって発表された研究によると、太りすぎの人の死亡率はBMIで定義された普通体重の人と同程度であり、痩せすぎや肥満の人の死亡率は高かった。

2009年にThe Lancetが発表した90万人の成人を対象とした研究によると、太りすぎの人と痩せすぎの人は、BMIで定義される標準体重の人よりも死亡率が高いことが示された。最適なBMIは22.5~25の範囲であることがわかった。アスリートの平均BMIは女性22.4、男性23.6である。

高BMIは、血清γ-グルタミルトランスペプチダーゼが高値の人においてのみ、2型糖尿病と関連する。

25万人を対象とした40の研究の分析では、BMIが「正常」な冠動脈疾患患者は、BMIが「過体重」(BMI25-29.9)の範囲にある患者よりも、心血管疾患による死亡リスクが高かった。

ある研究では、BMIは体脂肪率と一般的に良い相関関係があることを発見し、肥満は喫煙を抜いて世界第一の死因になっていることを指摘した。しかし、この研究では、体脂肪率による肥満の定義では男性の50%、女性の62%が肥満であったのに対し、BMIによる肥満の定義では男性の21%、女性の31%に過ぎず、BMIは肥満者の数を過小評価していることが判明したことも指摘している。

11,000人の被験者を最長8年間追跡調査した2010年の研究では、BMIは心臓発作、脳卒中、死亡のリスクを測る最も適切な指標ではないと結論づけられた。より適切な指標はウエスト対身長比であることが判明した。60,000人の被験者を13年間追跡した2011年の研究では、ウエスト-ヒップ比が虚血性心疾患死亡のより良い予測因子であることが判明した。

Limitations

The medical establishment and statistical community have both highlighted the limitations of BMI.

Racial and gender differences

Part of the statistical limitations of the BMI scale is the result of Quetelet's original sampling methods. As noted in his primary work, A Treatise on Man and the Development of His Faculties, the data from which Quetelet derived his formula was taken mostly from Scottish Highland soldiers and French Gendarmerie. The BMI was always designed as a metric for European men. For women, and people of non-European origin, the scale is often biased. As noted by sociologist Sabrina Strings, the BMI is largely inaccurate for black people especially, disproportionately labelling them as overweight even for healthy individuals.

Scaling

The exponent in the denominator of the formula for BMI is arbitrary. The BMI depends upon weight and the square of height. Since mass increases to the third power of linear dimensions, taller individuals with exactly the same body shape and relative composition have a larger BMI. BMI is proportional to the mass and inversely proportional to the square of the height. So, if all body dimensions double, and mass scales naturally with the cube of the height, then BMI doubles instead of remaining the same. This results in taller people having a reported BMI that is uncharacteristically high, compared to their actual body fat levels. In comparison, the Ponderal index is based on the natural scaling of mass with the third power of the height.

However, many taller people are not just "scaled up" short people but tend to have narrower frames in proportion to their height. Carl Lavie has written that "The B.M.I. tables are excellent for identifying obesity and body fat in large populations, but they are far less reliable for determining fatness in individuals."

For US adults, exponent estimates range from 1.92 to 1.96 for males and from 1.45 to 1.95 for females.

Physical characteristics

The BMI overestimates roughly 10% for a large (or tall) frame and underestimates roughly 10% for a smaller frame (short stature). In other words, people with small frames would be carrying more fat than optimal, but their BMI indicates that they are normal. Conversely, large framed (or tall) individuals may be quite healthy, with a fairly low body fat percentage, but be classified as overweight by BMI.

For example, a height/weight chart may say the ideal weight (BMI 21.5) for a 1.78-metre-tall (5 ft 10 in) man is 68 kilograms (150 lb). But if that man has a slender build (small frame), he may be overweight at 68 kg or 150 lb and should reduce by 10% to roughly 61 kg or 135 lb (BMI 19.4). In the reverse, the man with a larger frame and more solid build should increase by 10%, to roughly 75 kg or 165 lb (BMI 23.7). If one teeters on the edge of small/medium or medium/large, common sense should be used in calculating one's ideal weight. However, falling into one's ideal weight range for height and build is still not as accurate in determining health risk factors as waist-to-height ratio and actual body fat percentage.

Accurate frame size calculators use several measurements (wrist circumference, elbow width, neck circumference, and others) to determine what category an individual falls into for a given height. The BMI also fails to take into account loss of height through ageing. In this situation, BMI will increase without any corresponding increase in weight.

Muscle versus fat

Assumptions about the distribution between muscle mass and fat mass are inexact. BMI generally overestimates adiposity on those with leaner body mass (e.g., athletes) and underestimates excess adiposity on those with fattier body mass.

A study in June 2008 by Romero-Corral et al. examined 13,601 subjects from the United States' third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) and found that BMI-defined obesity (BMI ≥ 30) was present in 21% of men and 31% of women. Body fat-defined obesity was found in 50% of men and 62% of women. While BMI-defined obesity showed high specificity (95% for men and 99% for women), BMI showed poor sensitivity (36% for men and 49% for women). In other words, the BMI will be mostly correct when determining a person to be obese, but can err quite frequently when determining a person not to be. Despite this undercounting of obesity by BMI, BMI values in the intermediate BMI range of 20–30 were found to be associated with a wide range of body fat percentages. For men with a BMI of 25, about 20% have a body fat percentage below 20% and about 10% have body fat percentage above 30%.

Body composition for athletes is often better calculated using measures of body fat, as determined by such techniques as skinfold measurements or underwater weighing and the limitations of manual measurement have also led to new, alternative methods to measure obesity, such as the body volume indicator.

Variation in definitions of categories

It is not clear where on the BMI scale the threshold for overweight and obese should be set. Because of this, the standards have varied over the past few decades. Between 1980 and 2000 the U.S. Dietary Guidelines have defined overweight at a variety of levels ranging from a BMI of 24.9 to 27.1. In 1985 the National Institutes of Health (NIH) consensus conference recommended that overweight BMI be set at a BMI of 27.8 for men and 27.3 for women.

In 1998, an NIH report concluded that a BMI over 25 is overweight and a BMI over 30 is obese. In the 1990s the World Health Organization (WHO) decided that a BMI of 25 to 30 should be considered overweight and a BMI over 30 is obese, the standards the NIH set. This became the definitive guide for determining if someone is overweight.

One study found that the vast majority of people labelled 'overweight' and 'obese' according to current definitions do not in fact face any meaningful increased risk for early death. In a quantitative analysis of several studies, involving more than 600,000 men and women, the lowest mortality rates were found for people with BMIs between 23 and 29; most of the 25–30 range considered 'overweight' was not associated with higher risk.

Alternatives

Corpulence index (exponent of 3)

The corpulence index uses an exponent of 3 rather than 2. The corpulence index yields valid results even for very short and very tall people, which is a problem with BMI. For example, a 152.4 cm (5 ft 0 in) tall person at an ideal body weight of 48 kg (106 lb) gives a normal BMI of 20.74 and CI of 13.6, while a 200 cm (6 ft 7 in) tall person with a weight of 100 kg (220 lb) gives a BMI of 24.84, very close to an overweight BMI of 25, and a CI of 12.4, very close to a normal CI of 12.

New BMI (exponent of 2.5)

An exponent of 5/2 was proposed by Quetelet in the 19th century:

In general, we do not err much when we assume that during development the squares of the weight at different ages are as the fifth powers of the height

This exponent of 2.5 is used in a revised formula for Body Mass Index, proposed by Nick Trefethen, Professor of numerical analysis at the University of Oxford, which minimizes the distortions for shorter and taller individuals resulting from the use of an exponent of 2 in the traditional BMI formula:

The scaling factor of 1.3 was determined to make the proposed new BMI formula align with the traditional BMI formula for adults of average height, while the exponent of 2.5 is a compromise between the exponent of 2 in the traditional formula for BMI and the exponent of 3 that would be expected for the scaling of weight (which at constant density would theoretically scale with volume, i.e., as the cube of the height) with height. In Trefethen's analysis, an exponent of 2.5 was found to fit empirical data more closely with less distortion than either an exponent of 2 or 3.

BMI prime (exponent of 2, normalization factor)

BMI Prime, a modification of the BMI system, is the ratio of actual BMI to upper limit optimal BMI (currently defined at 25 kg/m2), i.e., the actual BMI expressed as a proportion of upper limit optimal. BMI Prime is a dimensionless number independent of units. Individuals with BMI Prime less than 0.74 are underweight; those with between 0.74 and 1.00 have optimal weight; and those at 1.00 or greater are overweight. BMI Prime is useful clinically because it shows by what ratio (e.g. 1.36) or percentage (e.g. 136%, or 36% above) a person deviates from the maximum optimal BMI.

For instance, a person with BMI 34 kg/m2 has a BMI Prime of 34/25 = 1.36, and is 36% over their upper mass limit. In South East Asian and South Chinese populations (see § international variations), BMI Prime should be calculated using an upper limit BMI of 23 in the denominator instead of 25. BMI Prime allows easy comparison between populations whose upper-limit optimal BMI values differ.

Waist circumference

Waist circumference is a good indicator of visceral fat, which poses more health risks than fat elsewhere. According to the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), waist circumference in excess of 1,020 mm (40 in) for men and 880 mm (35 in) for (non-pregnant) women is considered to imply a high risk for type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease CVD. Waist circumference can be a better indicator of obesity-related disease risk than BMI. For example, this is the case in populations of Asian descent and older people. 940 mm (37 in) for men and 800 mm (31 in) for women has been stated to pose "higher risk", with the NIH figures "even higher".

Waist-to-hip circumference ratio has also been used, but has been found to be no better than waist circumference alone, and more complicated to measure.

A related indicator is waist circumference divided by height. The values indicating increased risk are: greater than 0.5 for people under 40 years of age, 0.5 to 0.6 for people aged 40–50, and greater than 0.6 for people over 50 years of age.

Surface-based body shape index

The Surface-based Body Shape Index (SBSI) is far more rigorous and is based upon four key measurements: the body surface area (BSA), vertical trunk circumference (VTC), waist circumference (WC) and height (H). Data on 11,808 subjects from the National Health and Human Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) 1999–2004, showed that SBSI outperformed BMI, waist circumference, and A Body Shape Index (ABSI), an alternative to BMI.

A simplified, dimensionless form of SBSI, known as SBSI*, has also been developed.

Modified body mass index

Within some medical contexts, such as familial amyloid polyneuropathy, serum albumin is factored in to produce a modified body mass index (mBMI). The mBMI can be obtained by multiplying the BMI by serum albumin, in grams per litre.

こちらも参照

- Allometry/ja

- Body water/ja

- History of anthropometry/ja

- List of countries by body mass index/ja

- Obesity paradox/ja

- Relative Fat Mass/ja

- Somatotype and constitutional psychology/ja

さらに読む

- Ferrera LA, ed. (2006). Focus on Body Mass Index And Health Research. New York: Nova Science. ISBN 978-1-59454-963-2.

- Samaras TT, ed. (2007). Human Body Size and the Laws of Scaling: Physiological, Performance, Growth, Longevity and Ecological Ramifications. New York: Nova Science. ISBN 978-1-60021-408-0.

- Sothern MS, Gordon ST, von Almen TK, eds. (19 April 2016). Handbook of Pediatric Obesity: Clinical Management (Illustrated ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-1911-7.

外部リンク

- 米国国立保健統計センター:

- "BMI Growth Charts for children and young adults". US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 31 January 2019.

- "BMI calculator ages 20 and older". US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 21 July 2021.