Cheese/ja: Difference between revisions

Created page with "1860年代には、大量生産されたレンネットの始まりがあり、世紀の変わり目には、科学者たちは純粋な微生物培養物を生産していた。それ以前は、チーズ製造に使用されるバクテリアは環境からもたらされるか、以前の製造ロットのホエーを再利用したものであった。" |

No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

1860年代には、大量生産されたレンネットの始まりがあり、世紀の変わり目には、科学者たちは純粋な微生物培養物を生産していた。それ以前は、チーズ製造に使用されるバクテリアは環境からもたらされるか、以前の製造ロットのホエーを再利用したものであった。 | 1860年代には、大量生産されたレンネットの始まりがあり、世紀の変わり目には、科学者たちは純粋な微生物培養物を生産していた。それ以前は、チーズ製造に使用されるバクテリアは環境からもたらされるか、以前の製造ロットのホエーを再利用したものであった。 | ||

工場で製造されるチーズは、[[:ja:第二次世界大戦の|第二次世界大戦の]]時代に伝統的なチーズ製造を追い越し、それ以来、アメリカやヨーロッパではほとんどのチーズが工場で製造されるようになった。 2012年までに、チーズは世界中のスーパーマーケットで最も[[:ja:万引き|万引き]]された商品のひとつとなった。 | |||

工場で製造されるチーズは、[[:ja:第二次世界大戦の|第二次世界大戦の]] | |||

== 生産 == | |||

= | |||

{{Infobox agricultural production|plant=cheese|country6={{NLD}}|world=23.3|country10={{RUS}}|amount10=0.48|country9={{EGY}}|amount9=0.53|country8={{CAN}}|amount8=0.60|country7={{POL}}|amount7=0.77|amount6=0.95|amount1=9.83|country5={{ITA}}|amount5=1.30|country4={{FRA}}|amount4=1.61|country3={{GER}}|amount3=2.56|country2={{USA}}|amount2=6.16|country1={{EU}} (UK not included)|year=2019}}2014年の全乳チーズの世界生産量は1,870万トンで、米国が世界全体の29%(540万トン)を占め、次いでドイツ、フランス、イタリアが主要生産国となっている(表)。 | |||

{{Infobox agricultural production|plant=cheese|country6={{NLD}}|world=23.3|country10={{RUS}}|amount10=0.48|country9={{EGY}}|amount9=0.53|country8={{CAN}}|amount8=0.60|country7={{POL}}|amount7=0.77|amount6=0.95|amount1=9.83|country5={{ITA}}|amount5=1.30|country4={{FRA}}|amount4=1.61|country3={{GER}}|amount3=2.56|country2={{USA}}|amount2=6.16|country1={{EU}} (UK not included)|year=2019}} | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | <div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | ||

Revision as of 16:52, 28 June 2023

チーズは、乳タンパク質であるカゼインが凝固してできる乳製品で、様々な食感を持つ。乳(通常、牛、水牛、山羊、羊の乳)のタンパク質と脂肪から構成されている。製造時には、通常、牛乳を酸性にし、レンネットの酵素または同様の活性を持つ細菌の酵素を加えて、カゼインを凝固させる。その後、固形の凝乳が液体のホエーから分離され、プレスされて完成したチーズになる。チーズの中には、表皮や全体に芳香性のカビがあるものもある。

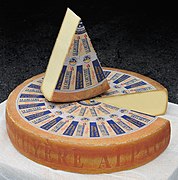

1000以上のチーズの種類が存在し、様々な国で生産されている。そのスタイル、テクスチャー、フレーバーは、乳の産地(動物の飼料を含む)、低温殺菌の有無、バター脂肪分、バクテリアやカビ、加工、そして熟成期間によって異なる。ハーブやスパイス、ウッドスモークなどを香味料として使用することもある。多くのチーズの黄色から赤色は、アナトを添加することによって生み出される。その他、黒胡椒、ニンニク、チャイブ、クランベリーなど、チーズに添加される成分もある。チーズ専門店(チーズの専門販売業者)は、チーズの選択、購入、入荷、保管、熟成に関する専門知識を有している場合がある。

一部のチーズでは、酢やレモン汁などの酸を加えることでミルクを凝固させる。ほとんどのチーズは、乳糖を乳酸に変えるバクテリアによって、より低い程度に酸性化され、レンネットを加えることで凝乳が完了する。レンネットに代わるベジタリアン用のものもあり、そのほとんどはムコール・ミーヘイという菌の発酵によって作られるが、その他にもシナノキ科の様々な種から抽出されたものもある。酪農地帯に近いチーズメーカーは、より新鮮で低価格の牛乳を手に入れることができ、輸送コストも抑えられるというメリットがある。

チーズは、持ち運びしやすく、賞味期限が長く、脂肪、タンパク質、カルシウム、リンを多く含むことから重宝されている。チーズの賞味期限はチーズの種類によって異なるが、牛乳よりもコンパクトで、賞味期限が長い。パルメザンチーズなどのハードチーズは、ブリーチーズや山羊乳チーズなどのソフトチーズよりも長持ちする。特に保護用の外皮に包まれたチーズは賞味期限が長いため、市場が好調な時に販売することができる。ブロック状のチーズの真空包装や、二酸化炭素と窒素の混合ガスによるプラスチック袋のガス充填は、21世紀のチーズの保管と大量流通に利用されている。

語源

チーズの語源はラテン語のcaseusで、現代語のcaseinもここから来ている。最も古い語源は、「発酵する、酸っぱくなる」を意味する原始インド・ヨーロッパ語族の語根*kwat-である。それがcīeseやcēse(古英語)やchese'(中英語)を生んだ。同様の単語は他の西ゲルマン諸語に共通する。西フリジア語のtsiis、オランダ語のkaas、ドイツ語の Käse、古高ドイツ語のchāsiはすべて、西ゲルマン語の*kāsīから再構築されたもので、ラテン語からの初期の借用語である。

オンライン語源辞典によれば、チーズの語源は以下の通りである:

古英語の cyse (西サクソン語)、 cese (アングリア語) ... 西ゲルマン語 *kasjus (古サクソン語 kasi, 古高ドイツ語 chasi, ドイツ語 Käse, 中オランダ語 case, オランダ語 kaasの語源である), ラテン語の caseus [for] "cheese" (イタリア語 cacio, スペイン語 queso, アイルランド後 caise, ウェールズ語 cawsの語源)に由来する。

オンライン後現時点は、この語の起源を次のように述べている:

おそらくPIE語源 *kwat- "発酵する、酸っぱくなる" (Prakrit chasi "buttermilk;" 古教会スラヴ語kvasu "発酵; 発酵飲料," kyselu "酸っぱい" -kyseti "酸っぱくなる" チェコ語 kysati "酸っぱくなる、腐る" サンスクリット語 kvathati "沸騰する、染みる" ゴート語 hwaþjan "泡")が語源であろう。fromageとも比較される。古ノルド語の ostr、デンマーク語の ost, スウェーデン語の ost は、ラテン語のius "スープ、ソース、ジュース"に関連している。

ローマ人がWhen the Romans began to make hard cheeses for their 軍団兵用のハードチーズを作り始めた時新しい単語が使われ始めた: formaticumは、caseus formatus、つまり"成形されたチーズ(molded cheese)" (カビが生えた(moldy)ではなく"成形された(formed)"の意)に由来する。フランス語のfromage、標準イタリア語の formaggio、 カタルーニャ語の formatge、 ブルトン語の fourmaj、オック語の fromatge (または formatge)は、この単語から派生したものである。ロマンス諸語のうち、スペイン語、ポルトガル語、ルーマニア語、トスカーナ語、南イタリア語の方言では、caseusに由来する単語が使われている (例えばqueso, queijo, caș, caso)。チーズ(cheese)という言葉自体が成形された 形成されたという意味で使われることもある。 ヘッドチーズは、この意味で使われている。また チーズ(cheese)という言葉は、名詞、動詞、形容詞として、多くの比喩的な表現に使われる (例えば、"the big cheese", "to be cheesed off", "cheesy lyrics"など)。

歴史

起源

チーズの起源は記録された歴史よりも古い。ヨーロッパ、中央アジア、中東など、どこでチーズ作りが始まったかを示す決定的な証拠はない。チーズ製造の起源を示す最も古い年代は、羊が初めて家畜化された紀元前8000年頃とされている。古来、動物の皮や膨らんだ内臓は、さまざまな食材の保存容器となっていたことから、チーズの製造工程は、動物の胃から作られた容器に牛乳を保存し、胃のレンネットによって牛乳が凝乳やホエーに変化することで偶然発見された可能性が高い。この方法で牛乳を保存していたアラブの商人がチーズを発見したという伝説がある。

考古学的記録におけるチーズ製造の最古の証拠は紀元前5500年にさかのぼり、現在のポーランドのクヤヴィアで発見されたもので、乳脂肪分子を塗ったストレーナーが見つかっている。

チーズ作りは、これとは別に、凝乳を圧搾して塩漬けにして保存することから始まったのかもしれない。動物の胃の中でチーズを作ると、凝乳がより固まり、きめが整うという観察から、意図的にレンネットを加えるようになったのかもしれない。エジプトのチーズに関する初期の考古学的証拠は、紀元前2000年頃のエジプト人の墓の壁画から見つかっている。2018年の科学論文では、紀元前約1200年(現在より3200年前)の世界最古のチーズが古代エジプトの墓から発見されたと述べられている。

最古のチーズはおそらくかなり酸っぱく塩辛いもので、素朴なカッテージチーズや、砕けやすく風味豊かなギリシャのチーズ、フェタに似た食感だった。中東よりも気候が涼しいヨーロッパで生産されたチーズは、保存に必要な塩分が少なかった。塩分と酸味が少ないため、チーズは有用な微生物やカビにとって適した環境となり、熟成したチーズにそれぞれの風味を与えるようになった。これまでに発見された最古の保存チーズは、中国の新疆ウイグル自治区にあるタクラマカン砂漠で発見されたもので、紀元前1615年(現在から3600年前)のものである。

古代ギリシャとローマ

古代ギリシャ神話では、アリスタイオスがチーズを発見したとされている。ホメロスのオデュッセイア(紀元前8世紀)には、キュクロプスが羊やヤギの乳のチーズを作り、貯蔵していたことが描かれている(サミュエル・バトラー訳):

私たちはすぐに彼の洞窟にたどり着いたが、彼は羊飼いに出かけていたので、中に入って目につくものをすべて調べた。彼のチーズ棚にはチーズが積まれ、小屋には入りきらないほどの子羊や子供がいた...。

そして、雌羊と子山羊の乳を搾り、それぞれに子供を産ませた。彼は乳の半分を凝固させ、籐の濾し器に入れて脇に置いた。

コルメラのDe Re Rustica(紀元65年頃)には、レンネット凝固、凝乳の圧搾、塩漬け、熟成を含むチーズ製造工程が詳述されている。長老プリニウスによれば、ローマ帝国が誕生する頃には、チーズ製造は洗練された事業になっていたという。プリニウスはまた、ヘルウェティイ族が生産していたスブリンツに似た硬いチーズ、カゼウス・ヘルヴェティコス(Caseus Helveticus)についても触れている。プリニウスの博物誌(紀元77年)は、一章(XI, 97)を割いて、帝国初期のローマ人が楽しんでいたチーズの多様性について述べている。彼は、最高のチーズはニーム近郊の村で作られるが、日持ちがしないため、新鮮なうちに食べなければならないと述べている。アルプスやアペニン山脈のチーズは、当時も現在と同じように、その種類の多さが際立っていた。リグーリア地方のチーズは、そのほとんどが羊の乳から作られていた。山羊乳のチーズはローマでは最近の嗜好品で、燻製にすることでガリアの似たようなチーズの薬っぽい味よりも改善された。海外産のチーズでは、プリニウスは小アジアのビティニアのチーズを好んだ。

ローマ帝国後のヨーロッパ

ローマ帝国時代の人々が、新しく定住するようになった馴染みのない隣人たちと出会い、彼ら独自のチーズ作りの伝統や家畜の群れ、チーズとは関係のない言葉を持ち込むようになると、ヨーロッパのチーズはさらに多様化し、さまざまな土地で独自の伝統や製品が生まれた。長距離交易が途絶えると、見知らぬチーズに出会うのは旅行者だけとなった: シャルルマーニュが初めて食用の白いチーズに出会ったのは、ノトケルの皇帝の生涯で構成された逸話のひとつである。

ブリティッシュ・チーズ・ボードによれば、イギリスにはおよそ700種類のチーズがあり、フランスとイタリアにはそれぞれ400種類ほどある(フランスのことわざでは、フランスには1年中毎日違うチーズがあるとされ、シャルル・ド・ゴールはかつて「246種類ものチーズがある国をどうやって統治するのか」と尋ねたことがある)。それでも、ヨーロッパにおけるチーズ芸術の進歩は、ローマ崩壊後の数世紀の間、遅々として進まなかった。今日人気のあるチーズの多くは、1500年頃のチェダー、1597年のパルメザン、1697年のゴーダ、1791年のカマンベールなど、中世後期以降に初めて記録されたものである。

1546年、ジョン・ヘイウッドの箴言は、「月は緑のチーズでできている」と主張した(グリーンはここで、現在多くの人が考えているように、色ではなく、新しい、あるいは未熟成であることを指しているのかもしれない)。NASAは2006年のエイプリルフールにこの神話を利用した。

現代

ヨーロッパ文化とともにチーズが近代的に広まるまで、チーズは東アジア文化圏やコロンブス以前のアメリカ大陸ではほとんど見られず、地中海以南のアフリカでも限られた地域でしか使われていなかった。主に、ヨーロッパ、中東、インド亜大陸、およびそれらの文化の影響を受けた地域にのみ広まり、普及していた。 しかし、最初にヨーロッパ帝国主義が広まり、後にヨーロッパ系アメリカ人の文化や食文化が広まるにつれて、チーズは徐々に世界中に知られるようになり、ますます人気が高まっていった。

1815年にスイスで最初のチーズ工業生産工場が開設されたが、大規模な生産が本格的に成功したのはアメリカが最初である。1851年、ニューヨーク州ローマの酪農家ジェシー・ウィリアムズが、近隣の農場の牛乳を使い、組み立て式でチーズを作り始めたのだ。これにより、チェダー・チーズは米国初の工業用食品のひとつとなった。数十年のうちに、このような商業的酪農組合が何百も存在するようになった。

1860年代には、大量生産されたレンネットの始まりがあり、世紀の変わり目には、科学者たちは純粋な微生物培養物を生産していた。それ以前は、チーズ製造に使用されるバクテリアは環境からもたらされるか、以前の製造ロットのホエーを再利用したものであった。

工場で製造されるチーズは、第二次世界大戦の時代に伝統的なチーズ製造を追い越し、それ以来、アメリカやヨーロッパではほとんどのチーズが工場で製造されるようになった。 2012年までに、チーズは世界中のスーパーマーケットで最も万引きされた商品のひとつとなった。

生産

| Top cheese producers | |

|---|---|

| in 2019 | |

| Numbers in million tonnes | |

| 1. | 9.83 |

| 2. | 6.16 |

| 3. | 2.56 |

| 4. | 1.61 |

| 5. | 1.30 |

| 6. | 0.95 |

| 7. | 0.77 |

| 8. | 0.60 |

| 9. | 0.53 |

| 10. | 0.48 |

| World total | 23.3 |

| Source: UN Food and Agriculture Organization | |

2014年の全乳チーズの世界生産量は1,870万トンで、米国が世界全体の29%(540万トン)を占め、次いでドイツ、フランス、イタリアが主要生産国となっている(表)。

Other 2014 world totals for processed cheese include:

- from skimmed cow milk, 2.4 million tonnes (leading country, Germany, 845,500 tonnes)

- from goat milk, 523,040 tonnes (leading country, South Sudan, 110,750 tonnes)

- from sheep milk, 680,302 tonnes (leading country, Greece, 125,000 tonnes)

- from buffalo milk, 282,127 tonnes (leading country, Egypt, 254,000 tonnes)

During 2015, Germany, France, Netherlands and Italy exported 10–14% of their produced cheese. The United States was a marginal exporter (5.3% of total cow milk production), as most of its output was for the domestic market.

The carbon footprint of a kilogram of cheese ranges from 6 to 12 kg of CO2eq, depending on the amount of milk used; thus it is generally lower than beef or lamb but higher than other foods.

Consumption

France, Iceland, Finland, Denmark and Germany were the highest consumers of cheese in 2014, averaging 25 kg (55 lb) per person per annum.

Processing

Curdling

A required step in cheesemaking is separating the milk into solid curds and liquid whey. Usually this is done by acidifying (souring) the milk and adding rennet. The acidification can be accomplished directly by the addition of an acid, such as vinegar, in a few cases (paneer, queso fresco). More commonly starter bacteria are employed instead which convert milk sugars into lactic acid. The same bacteria (and the enzymes they produce) also play a large role in the eventual flavor of aged cheeses. Most cheeses are made with starter bacteria from the Lactococcus, Lactobacillus, or Streptococcus genera. Swiss starter cultures also include Propionibacter shermani, which produces propionic acid and carbon dioxide gas bubbles during aging, giving Swiss cheese or Emmental its holes (called "eyes").

Some fresh cheeses are curdled only by acidity, but most cheeses also use rennet. Rennet sets the cheese into a strong and rubbery gel compared to the fragile curds produced by acidic coagulation alone. It also allows curdling at a lower acidity—important because flavor-making bacteria are inhibited in high-acidity environments. In general, softer, smaller, fresher cheeses are curdled with a greater proportion of acid to rennet than harder, larger, longer-aged varieties.

While rennet was traditionally produced via extraction from the inner mucosa of the fourth stomach chamber of slaughtered young, unweaned calves, most rennet used today in cheesemaking is produced recombinantly. The majority of the applied chymosin is retained in the whey and, at most, may be present in cheese in trace quantities. In ripe cheese, the type and provenance of chymosin used in production cannot be determined.

Curd processing

At this point, the cheese has set into a very moist gel. Some soft cheeses are now essentially complete: they are drained, salted, and packaged. For most of the rest, the curd is cut into small cubes. This allows water to drain from the individual pieces of curd.

Some hard cheeses are then heated to temperatures in the range of 35–55 °C (95–131 °F). This forces more whey from the cut curd. It also changes the taste of the finished cheese, affecting both the bacterial culture and the milk chemistry. Cheeses that are heated to the higher temperatures are usually made with thermophilic starter bacteria that survive this step—either Lactobacilli or Streptococci.

Salt has roles in cheese besides adding a salty flavor. It preserves cheese from spoiling, draws moisture from the curd, and firms cheese's texture in an interaction with its proteins. Some cheeses are salted from the outside with dry salt or brine washes. Most cheeses have the salt mixed directly into the curds.

Other techniques influence a cheese's texture and flavor. Some examples are:

- Stretching: (Mozzarella, Provolone) the curd is stretched and kneaded in hot water, developing a stringy, fibrous body.

- Cheddaring: (Cheddar, other English cheeses) the cut curd is repeatedly piled up, pushing more moisture away. The curd is also mixed (or milled) for a long time, taking the sharp edges off the cut curd pieces and influencing the final product's texture.

- Washing: (Edam, Gouda, Colby) the curd is washed in warm water, lowering its acidity and making for a milder-tasting cheese.

Most cheeses achieve their final shape when the curds are pressed into a mold or form. The harder the cheese, the more pressure is applied. The pressure drives out moisture—the molds are designed to allow water to escape—and unifies the curds into a single solid body.

Ripening

A newborn cheese is usually salty yet bland in flavor and, for harder varieties, rubbery in texture. These qualities are sometimes enjoyed—cheese curds are eaten on their own—but normally cheeses are left to rest under controlled conditions. This aging period (also called ripening, or, from the French, affinage) lasts from a few days to several years. As a cheese ages, microbes and enzymes transform texture and intensify flavor. This transformation is largely a result of the breakdown of casein proteins and milkfat into a complex mix of amino acids, amines, and fatty acids.

Some cheeses have additional bacteria or molds intentionally introduced before or during aging. In traditional cheesemaking, these microbes might be already present in the aging room; they are allowed to settle and grow on the stored cheeses. More often today, prepared cultures are used, giving more consistent results and putting fewer constraints on the environment where the cheese ages. These cheeses include soft ripened cheeses such as Brie and Camembert, blue cheeses such as Roquefort, Stilton, Gorgonzola, and rind-washed cheeses such as Limburger.

Types

There are many types of cheese, with around 500 different varieties recognized by the International Dairy Federation, more than 400 identified by Walter and Hargrove, more than 500 by Burkhalter, and more than 1,000 by Sandine and Elliker. The varieties may be grouped or classified into types according to criteria such as length of ageing, texture, methods of making, fat content, animal milk, country or region of origin, etc.—with these criteria either being used singly or in combination, but with no single method being universally used. The method most commonly and traditionally used is based on moisture content, which is then further discriminated by fat content and curing or ripening methods. Some attempts have been made to rationalise the classification of cheese—a scheme was proposed by Pieter Walstra which uses the primary and secondary starter combined with moisture content, and Walter and Hargrove suggested classifying by production methods which produces 18 types, which are then further grouped by moisture content.

-

Brie cheese

-

Maccagno cheese

-

Bergader Almkase cheese

-

Sheep milk cheese from Poland

-

Devil's Gulch cheese

-

Saint-Julien aux noix

-

Bavaria blu cheese

-

Tentation du Vercors

-

Météorite fromage

-

Österkron blue cheese

-

Isle of Mull Cheese

-

Zacharie cheese

-

Diverse Sauermilchkäse sour cheese

-

Brie de Nangis

-

Rouelle du Tarn

Cooking and eating

At refrigerator temperatures, the fat in a piece of cheese is as hard as unsoftened butter, and its protein structure is stiff as well. Flavor and odor compounds are less easily liberated when cold. For improvements in flavor and texture, it is widely advised that cheeses be allowed to warm up to room temperature before eating. If the cheese is further warmed, to 26–32 °C (79–90 °F), the fats will begin to "sweat out" as they go beyond soft to fully liquid.

Above room temperatures, most hard cheeses melt. Rennet-curdled cheeses have a gel-like protein matrix that is broken down by heat. When enough protein bonds are broken, the cheese itself turns from a solid to a viscous liquid. Soft, high-moisture cheeses will melt at around 55 °C (131 °F), while hard, low-moisture cheeses such as Parmesan remain solid until they reach about 82 °C (180 °F). Acid-set cheeses, including halloumi, paneer, some whey cheeses and many varieties of fresh goat cheese, have a protein structure that remains intact at high temperatures. When cooked, these cheeses just get firmer as water evaporates.

Some cheeses, like raclette, melt smoothly; many tend to become stringy or suffer from a separation of their fats. Many of these can be coaxed into melting smoothly in the presence of acids or starch. Fondue, with wine providing the acidity, is a good example of a smoothly melted cheese dish. Elastic stringiness is a quality that is sometimes enjoyed, in dishes including pizza and Welsh rarebit. Even a melted cheese eventually turns solid again, after enough moisture is cooked off. The saying "you can't melt cheese twice" (meaning "some things can only be done once") refers to the fact that oils leach out during the first melting and are gone, leaving the non-meltable solids behind.

As its temperature continues to rise, cheese will brown and eventually burn. Browned, partially burned cheese has a particular distinct flavor of its own and is frequently used in cooking (e.g., sprinkling atop items before baking them).

A cheeseboard (or cheese course) may be served at the end of a meal before or following dessert, or replacing the last course. The British tradition is to have cheese after dessert, accompanied by sweet wines like Port. In France, cheese is consumed before dessert, with robust red wine. A cheeseboard typically has contrasting cheeses with accompaniments, such as crackers, biscuits, grapes, nuts, celery or chutney. A typical cheeseboard may contain four to six cheeses, for example: Mature Cheddar or Comté (hard: cow's milk cheeses); Brie or Camembert (soft: cow's milk); a blue cheese such as Stilton (hard: cow's milk), Roquefort (medium: ewe's milk) or Bleu d'Auvergne (medium-soft cow's milk); a soft/medium-soft goat's cheese (e.g. Sainte-Maure de Touraine, Pantysgawn, Crottin de Chavignol). A cheeseboard 70 feet (21 m) long was used to feature the variety of cheeses manufactured in Wisconsin, where the state legislature recognizes a "cheesehead" hat as a state symbol.

Nutrition and health

The nutritional value of cheese varies widely. Cottage cheese may consist of 4% fat and 11% protein while some whey cheeses are 15% fat and 11% protein, and triple-crème cheeses are 36% fat and 7% protein. In general, cheese is a rich source (20% or more of the Daily Value, DV) of calcium, protein, phosphorus, sodium and saturated fat. A 28-gram (one ounce) serving of cheddar cheese contains about 7 grams (0.25 oz) of protein and 202 milligrams of calcium. Nutritionally, cheese is essentially concentrated milk, but altered by the culturing and aging processes: it takes about 200 grams (7.1 oz) of milk to provide that much protein, and 150 grams (5.3 oz) to equal the calcium, though values for water-soluble vitamins and minerals can vary widely.

| Water | Protein | Fat | Carbs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swiss | 37.1 | 26.9 | 27.8 | 5.4 |

| Feta | 55.2 | 14.2 | 21.3 | 4.1 |

| Cheddar | 36.8 | 24.9 | 33.1 | 1.3 |

| Mozzarella | 50 | 22.2 | 22.4 | 2.2 |

| Cottage | 80 | 11.1 | 4.3 | 3.4 |

| A | B1 | B2 | B3 | B5 | B6 | B9 | B12 | C | D | E | K | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swiss | 17 | 4 | 17 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 56 | 0 | 11 | 2 | 3 |

| Feta | 8 | 10 | 50 | 5 | 10 | 21 | 8 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Cheddar | 20 | 2 | 22 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 14 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| Mozzarella | 14 | 2 | 17 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 38 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Cottage | 3 | 2 | 10 | 0 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cl | Ca | Fe | Mg | P | K | Na | Zn | Cu | Mn | Se | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swiss | 2.8 | 79 | 10 | 1 | 57 | 2 | 8 | 29 | 2 | 0 | 26 |

| Feta | 2.2 | 49 | 4 | 5 | 34 | 2 | 46 | 19 | 2 | 1 | 21 |

| Cheddar | 3 | 72 | 4 | 7 | 51 | 3 | 26 | 21 | 2 | 1 | 20 |

| Mozzarella | 2.8 | 51 | 2 | 5 | 35 | 2 | 26 | 19 | 1 | 1 | 24 |

| Cottage | 3.3 | 8 | 0 | 2 | 16 | 3 | 15 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 14 |

Nutrient data from SELF.com. Abbreviations: Cl = Choline; Ca = Calcium; Fe = Iron; Mg = Magnesium; P = Phosphorus; K = Potassium; Na = Sodium; Zn = Zinc; Cu = Copper; Mn = Manganese; Se = Selenium.

Cardiovascular disease

National health organizations, such as the American Heart Association, Association of UK Dietitians|British Dietetic Association|Association of UK Dietitians, British National Health Service, and Mayo Clinic, among others, recommend that cheese consumption be minimized, replaced in snacks and meals by plant foods, or restricted to low-fat cheeses to reduce caloric intake and blood levels of LDL fat, which is a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases. There is no high-quality clinical evidence that cheese consumption lowers the risk of cardiovascular diseases.

Pasteurization

A number of food safety agencies around the world have warned of the risks of raw-milk cheeses. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration states that soft raw-milk cheeses can cause "serious infectious diseases including listeriosis, brucellosis, salmonellosis and tuberculosis". It is U.S. law since 1944 that all raw-milk cheeses (including imports since 1951) must be aged at least 60 days. Australia has a wide ban on raw-milk cheeses as well, though in recent years exceptions have been made for Swiss Gruyère, Emmental and Sbrinz, and for French Roquefort. There is a trend for cheeses to be pasteurized even when not required by law.

Pregnant women may face an additional risk from cheese; the U.S. Centers for Disease Control has warned pregnant women against eating soft-ripened cheeses and blue-veined cheeses, due to the listeria risk, which can cause miscarriage or harm the fetus.

Cultural attitudes

Although cheese is a vital source of nutrition in many regions of the world and it is extensively consumed in others, its use is not universal.

Cheese is rarely found in Southeast and East Asian cuisines, presumably for historical reasons as dairy farming has historically been rare in these regions, due in part to low rates of lactase persistence. Paneer (pronounced [pəniːr]) is a fresh cheese common in North India and Pakistan. It is an unaged, non-melting soft cheese made by curdling milk with a fruit- or vegetable-derived acid, such as lemon juice. Its acid-set form (cheese curd), before pressing, is called chhena. In Nepal, the Dairy Development Corporation commercially manufactures cheese made from yak milk and a hard cheese made from either cow or yak milk known as chhurpi. Bhutan also produces a similar cheese called Datshi which is a staple in most Bhutanese curries. The national dish of Bhutan, ema datshi, is made from homemade yak or mare milk cheese and hot peppers. In Yunnan, China, several ethnic minority groups produce Rushan and Rubing from cow's milk. Cheese consumption may be increasing in China, with annual sales doubling from 1996 to 2003 (to a still small 30 million U.S. dollars a year). Certain kinds of Chinese preserved bean curd are sometimes misleadingly referred to in English as "Chinese cheese" because of their texture and strong flavor.

Strict followers of the dietary laws of Islam and Judaism must avoid cheeses made with rennet from animals not slaughtered in a manner adhering to halal or kosher laws. Both faiths allow cheese made with vegetable-based rennet or with rennet made from animals that were processed in a halal or kosher manner. Many less orthodox Jews also believe that rennet undergoes enough processing to change its nature entirely and do not consider it to ever violate kosher law (see Cheese and kashrut). As cheese is a dairy food, under kosher rules it cannot be eaten in the same meal with any meat.

Rennet derived from animal slaughter, and thus cheese made with animal-derived rennet, is not vegetarian. Most widely available vegetarian cheeses are made using rennet produced by fermentation of the fungus Mucor miehei. Vegans and other dairy-avoiding vegetarians do not eat conventional cheese, but some vegetable-based cheese substitutes (soy or almond) are used as substitutes.

Collecting cheese labels is called "tyrosemiophilia".

Odorous cheeses

Even in cultures with long cheese traditions, consumers may perceive some cheeses that are especially pungent-smelling, or mold-bearing varieties such as Limburger or Roquefort, as unpalatable. Such cheeses are an acquired taste because they are processed using molds or microbiological cultures, allowing odor and flavor molecules to resemble those in rotten foods. One author stated: "An aversion to the odor of decay has the obvious biological value of steering us away from possible food poisoning, so it is no wonder that an animal food that gives off whiffs of shoes and soil and the stable takes some getting used to".

Effect on sleep

There is some support from studies that dairy products can help with insomnia.

Scientists have debated how cheese might affect sleep. An antithetical folk belief that cheese eaten close to bedtime can cause nightmares may have arisen from the Charles Dickens novella A Christmas Carol, in which Ebenezer Scrooge attributes his visions of Jacob Marley to the cheese he ate. This belief can also be found in folklore that predates this story. The theory has been disproven multiple times, although night cheese may cause vivid dreams or otherwise disrupt sleep due to its high saturated fat content, according to studies by the British Cheese Board. Other studies indicate it may actually make people dream less.

比喩的な表現

In the 19th century, "cheese" was used as a figurative way of saying "the proper thing"; this usage comes from Urdu cheez "a thing", from Persian cheez, from Old Persian...ciš-ciy [which means] "something". The term "cheese" in this sense was "[p]icked up by [colonial] British in India by 1818 and [was also] used in the sense of "a big thing", for example in the expression "he's the real cheez". The expression "big cheese" was attested in use in 1914 to mean an "important person"; this is likely "American English in origin". The expression "to cut a big cheese" was used to mean "to look important"; this figurative expression referred to the huge wheels of cheese displayed by cheese retailers as a publicity stunt. The phrase "cut the cheese" also became an American slang term meaning to flatulate. The word "cheese" has also had the meaning of "an ignorant, stupid person".

Other figurative meanings involve the word "cheese" used as a verb. To "cheese" is recorded as meaning to "stop (what one is doing), run off", in 1812 (this was "thieves' slang"). To be "cheesed off" means to be annoyed. The expression "say 'cheese'" in a photograph-taking context (when the photographer wants the people to smile for the photo), which means "smile", dates from 1930 (the word was probably chosen because the "ee" encourages people to make a smile). The verb "cheese" was used as slang for "be quiet" in the early 19th century in Britain. The fictional "...notion that the moon is made of green cheese as a type of a ridiculous assertion is from 1520s". The figurative expression "to make cheeses" is an 1830s phrase referring to schoolgirls who amuse themselves by "...wheeling rapidly so one's petticoats blew out in a circle then dropping down so they came to rest inflated and resembling a wheel of cheese". In video game slang "to cheese it" means to win a game by using a strategy that requires minimal skill and knowledge or that exploits a glitch or flaw in game design.

The adjective "cheesy" has two meanings. The first is literal, and means "cheese-like"; this definition is attested to from the late 14th century (e.g., "a cheesy substance oozed from the broken jar"). In the late 19th century, medical writers used the term "cheesy" in a more literal sense, "to describe morbid substances found in tumors, decaying flesh, etc." The adjective also has a figurative sense, meaning "cheap, inferior"; this use "... is attested from 1896, perhaps originally U.S. student slang". In the late 19th century in British slang, "cheesy" meant "fine, showy"; this use is attested to in the 1850s. In writing lyrics for pop music, rock music or musical theatre, "cheesy" is a pejorative term which means "blatantly artificial" (OED).

See also

Bibliography

- Ensrud, Barbara (1981). The Pocket Guide to Cheese. Sydney: Lansdowne Press. ISBN 978-0-7018-1483-0.

- Jenkins, Steven (1996). Cheese Primer. Workman Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-89480-762-6.

- Mellgren, James (2003). "2003 Specialty Cheese Manual, Part II: Knowing the Family of Cheese". Archived from the original on June 24, 2003. Retrieved October 12, 2005.

Further reading

- Layton, T.A. (1967) The ... Guide to Cheese and Cheese Cookery. London: Wine and Food Society (reissued by the Cookery Book Club, 1971)

- Buckingham, Cheyenne (May 1, 2019). "Is It Bad to Eat Cheese With Mold On It?". Eat This, Not That!.

External links

- Cheese.com – includes an extensive database of different types of cheese.

- Classification of cheese – why is one cheese type different from another?

| この記事は、クリエイティブ・コモンズ・表示・継承ライセンス3.0のもとで公表されたウィキペディアの項目Cheeseを翻訳して二次利用しています。 |