Climate change mitigation/ja: Difference between revisions

Created page with "新しい原子炉の建設には現在約10年かかり、これは風力発電や太陽光発電の導入拡大よりもはるかに長い。そして、この期間は信用リスクを生じさせる。しかし、中国では原子力がはるかに安価である可能性がある。中国は相当数の新しい発電所を建設している。2019年時点で、原子力の廃棄物処分の長期費用を計算から除外した場合、原子力発電所の寿..." |

No edit summary |

||

| (144 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 116: | Line 116: | ||

新しい原子炉の建設には現在約10年かかり、これは風力発電や太陽光発電の導入拡大よりもはるかに長い。そして、この期間は信用リスクを生じさせる。しかし、中国では原子力がはるかに安価である可能性がある。中国は相当数の新しい発電所を建設している。2019年時点で、原子力の廃棄物処分の長期費用を計算から除外した場合、原子力発電所の寿命延長費用は他の発電技術と競争力がある。また、原子力事故に対する十分な財政保険も存在しない。 | 新しい原子炉の建設には現在約10年かかり、これは風力発電や太陽光発電の導入拡大よりもはるかに長い。そして、この期間は信用リスクを生じさせる。しかし、中国では原子力がはるかに安価である可能性がある。中国は相当数の新しい発電所を建設している。2019年時点で、原子力の廃棄物処分の長期費用を計算から除外した場合、原子力発電所の寿命延長費用は他の発電技術と競争力がある。また、原子力事故に対する十分な財政保険も存在しない。 | ||

=== 石炭を天然ガスに置き換える === | |||

{{excerpt|sustainable energy/ja#化石燃料の転換と緩和策|paragraphs=1-2|file=no}} | |||

{{excerpt|sustainable energy# | |||

==需要削減== | |||

== | {{Further/ja|:en:Individual action on climate change}} | ||

{{Further|Individual action on climate change}} | 温室効果ガス排出を引き起こす製品やサービスへの需要を減らすことは、気候変動の緩和に役立つ。一つは、[[:en:Individual action on climate change|行動や文化の変化]]によって需要を減らすことである。例えば、食事を変えること、特に食肉消費を減らすという決定は、[[:en:Individual action on climate change|個人が気候変動と闘うための効果的な行動]]である。もう一つは、公共交通機関ネットワークの整備など、インフラを改善することによって需要を減らすことである。最後に、最終用途技術の変化によってエネルギー需要を減らすことができる。例えば、断熱性の良い家は、断熱性の悪い家よりも排出量が少ない。 | ||

製品やサービスへの需要を減らす緩和策は、人々が自身の[[:en:carbon footprint|炭素排出量]]を削減するための個人的な選択をするのに役立つ。これは交通手段や食品の選択において当てはまる。したがって、これらの緩和策には需要削減に焦点を当てた多くの社会側面があり、それゆえ「需要側」の「緩和行動」である。例えば、社会経済的地位が高い人々は、低い人々よりも多くの温室効果ガス排出量を引き起こすことが多い。もし彼らが排出量を削減し、グリーン政策を推進すれば、これらの人々は低炭素ライフスタイルのロールモデルになる可能性がある。しかし、消費者には意識や知覚されたリスクなど、多くの心理的変数が影響を与える。 | |||

政府の政策は、需要側の気候変動緩和策を支援することも、妨げることもあり得ます。例えば、公共政策は、[[:en:circular economy|循環経済]]の概念を推進することで気候変動緩和を支援できます。温室効果ガス排出量の削減は、[[:en:sharing economy|シェアリングエコノミー]]とも関連している。 | |||

経済成長と排出量の相関関係については議論がある。経済成長が必ずしも排出量の増加を意味するわけではなくなってきているようだ。 | |||

2024年に『ネイチャー・クライメート・チェンジ』誌に掲載された論文は、気候変動緩和戦略に行動科学を統合することの重要性を強調している。 | |||

この論文では、温室効果ガス排出量削減に向けた個人および集団の行動を改善するための6つの主要な提言が示されている。これには、研究における障壁の克服、学際的な協力の促進、実践的な行動志向型ソリューションの推進などが含まれる。 | |||

これらの洞察は、気候変動への対処において、行動科学が技術的・政策的措置と並んで極めて重要な役割を果たすことを示唆している。 | |||

===エネルギー保全と効率=== | |||

=== | {{Main/ja|:en:Energy conservation|:en:Efficient energy use}} | ||

{{Main| | 2018年には、世界の一次エネルギー需要が161,000テラワット時(TWh)を超えた。これは、電力、輸送、暖房の全てを含み、その際の損失も考慮した数値である。 | ||

特に輸送と電力生産において、化石燃料の利用効率は50%未満と低い。発電所や車両のモーターからは大量の熱が無駄に排出されている。実際に消費されたエネルギー量は大幅に少なく、116,000 TWhにとどまっている。 | |||

[[:en:Energy conservation|エネルギー保全]]とは、[[:en:Energy consumption|エネルギー消費量]]を減らすために、エネルギーサービスの使用量を減らす努力である。一つの方法は、[[:en:Efficient energy use|エネルギーをより効率的に利用する]]ことである。これは、同じサービスを生産するために、以前よりも少ないエネルギーを使用することを意味する。もう一つの方法は、使用するサービスの量を減らすことである。これの例としては、運転を減らすことなどが挙げられる。エネルギー保全は、持続可能なエネルギーのヒエラルキーの頂点に位置する。消費者が無駄や損失を減らすことで、エネルギーを保全できる。技術のアップグレード、および運用と保守の改善は、全体的な効率改善につながる。 | |||

[[Energy conservation]] | |||

[[:en:Efficient energy use|エネルギー効率]](または「エネルギー効率化」)とは、製品やサービスを提供するために必要なエネルギー量を削減するプロセスである。[[:en:Energy-efficient building|建物のエネルギー効率]](「グリーンビルディング」)、工業プロセス、および輸送の改善は、2050年までに世界のエネルギー需要を3分の1削減できる可能性がある。これは、温室効果ガスの世界的排出量を削減するのに役立つだろう。例えば、建物を断熱することで、熱的快適性を達成および維持するために必要な暖房および冷房エネルギーの使用量を減らすことができる。エネルギー効率の改善は、一般により効率的な技術や生産プロセスを採用することによって達成される。もう一つの方法は、一般的に受け入れられている方法を用いてエネルギー損失を減らすことである。 | |||

[[Efficient energy use]] | |||

===ライフスタイルの変化=== | |||

[[File:2019 Carbon dioxide emissions by income group - Oxfam data.svg|thumb|upright=1.2|この円グラフは、所得グループごとの総排出量と、各所得グループ内での一人当たりの排出量の両方を示している。例えば、所得が最も高い10%の層は炭素排出量の半分を占めており、その構成員は所得規模の下位半分に属する構成員の一人当たり排出量の平均5倍以上を排出している。]] | |||

[[File:2019 Carbon dioxide emissions by income group - Oxfam data.svg|thumb|upright=1.2| | |||

[[:en:Individual action on climate change|気候変動に関する個人の行動]]は、多くの分野における個人的な選択を含みうる。これらには、食事、旅行、家庭でのエネルギー使用、商品やサービスの消費、家族構成などが含まれる。自身の[[:en:carbon footprint|炭素排出量]]を削減したいと願う人々は、[[:en:frequent flying|頻繁な飛行機利用]]やガソリン車の回避、主に[[plant-based diet/ja|植物ベースの食事]]を摂ること、子どもの数を減らすこと、衣類や電気製品を長く使うことなど、影響の大きい行動をとることができる。これらのアプローチは、高消費型のライフスタイルを持つ高所得国の国民にとってより現実的である。当然ながら、電気自動車のような選択肢が利用できないため、低所得層の人々がこれらの変化を起こすことはより困難である。気候変動の原因としては、人口増加よりも過剰消費の方がより大きな責任がある。高消費型のライフスタイルは環境への影響が大きく、最も裕福な10%の人々がライフスタイルに起因する総排出量の約半分を排出している。 | |||

[[Individual action on climate change]] | |||

=== 食生活の変更 === | |||

= | {{main/ja|Low-carbon diet/ja|Plant-based diet/ja}} | ||

{{main|Low-carbon diet|Plant-based diet}} | |||

一部の科学者によると、食肉と乳製品を避けることが、個人が環境負荷を減らす最も大きな方法であるという。菜食主義の食事が広く採用されれば、食品関連の温室効果ガス排出量を2050年までに63%削減できる可能性がある。中国は2016年に新しい食事ガイドラインを導入し、肉の消費量を50%削減し、それによって2030年までに年間1ギガトン(Gt)の温室効果ガス排出量を削減することを目指している。全体として、食品は消費ベースの温室効果ガス排出量の中で最大の割合を占めている。それは世界の[[:en:carbon footprint|カーボンフットプリント]]の約20%を占めている。全人為起源の温室効果ガス排出量のほぼ15%は、家畜部門に起因するとされている。 | |||

[[plant-based diets/ja|植物性食生活]]への移行は、気候変動の緩和に大きく貢献する。 特に、食肉消費を減らすことは、メタン排出量の削減に役立つ。もし高所得国が植物性食生活に切り替えた場合、畜産に利用されている広大な土地を[[:en:Restoration ecology|自然の状態に戻す]]ことが可能になる。これにより、今世紀末までに1000億トンの{{CO2}}を隔離できる可能性がある。 | |||

包括的な分析によると、植物性食生活は排出量、水質汚染、土地利用を大幅に(75%も)削減する一方で、野生生物の破壊と水の使用量も減らすことが明らかになっている。 | |||

[[File:GHG by diet groups.svg|thumb|right| | [[File:GHG by diet groups.svg|thumb|right|食事グループ別(Nat Food 4, 565–574, 2023)英国市民55,504人の環境フットプリント]] | ||

=== 家族の規模 === | |||

== | {{Further/ja|:en:Individual action on climate change#Family size}}[[File:World population (UN).svg|thumb|right|upright=1.35|1950年以降、世界人口は3倍になった。]] | ||

{{Further|Individual action on climate change#Family size}}[[File:World population (UN).svg|thumb|right|upright=1.35| | [[:en:Projections of population growth|人口増加]]は、ほとんどの地域、特にアフリカにおいて温室効果ガス排出量の増加をもたらしている。しかし、経済成長は人口増加よりも大きな影響を与える。所得の増加、消費と食事パターンの変化、そして人口増加は、土地やその他の天然資源に圧力をかける。これにより、温室効果ガス排出量が増加し、炭素吸収源が減少する。一部の学者は、人口増加を抑制するための人道主義的な政策は、化石燃料の使用を終わらせ、持続可能な消費を奨励する政策とともに、広範な気候変動対策の一部であるべきだと主張している。女性の教育と[[:en:Sexual and reproductive health|性と生殖に関する健康]]、特に家族計画の進歩は、人口増加の削減に貢献できる。 | ||

==炭素吸収源の保全と強化== | |||

[[File:Carbon Dioxide Partitioning.svg|thumb|upright=1.35|right|[[:en:Global Carbon Project#Global Carbon Budget|2020年グローバル・カーボン・バジェット]]によると、{{CO2}}排出量の約58%は、植物の成長、土壌吸収、海洋吸収を含む[[:en:carbon sink|炭素吸収源]]によって吸収されている。]] | |||

[[File:Carbon Dioxide Partitioning.svg|thumb|upright=1.35|right| | {{Main/ja|Carbon dioxide removal|:en:Carbon sequestration|:en:Carbon sink}} | ||

{{Main|Carbon dioxide removal|Carbon sequestration|Carbon sink}} | |||

重要な緩和策の一つは、「[[:en:carbon sink|炭素吸収源]]の保全と強化」である。これは、地球の自然な[[:en:carbon sink|炭素吸収源]]を管理し、大気からCO<sub>2</sub>を除去し、それを永続的に貯蔵する能力を維持または増加させることを指す。科学者たちはこのプロセスを[[:en:carbon sequestration|炭素隔離]]とも呼ぶ。気候変動緩和の文脈において、IPCCは「吸収源(シンク)」を「大気から温室効果ガス、エアロゾル、または温室効果ガスの前駆体を除去するあらゆるプロセス、活動、メカニズム」と定義している。世界的に、最も重要な2つの炭素吸収源は植生と海洋である。 | |||

[[:en:ecosystem|生態系]]の炭素隔離能力を高めるためには、農業と林業において変化が必要である。例としては、[[:en:deforestation|森林伐採]]を防ぎ、[[:en:reforestation|再植林]]によって自然生態系を復元することなどが挙げられる。地球温暖化を1.5℃に制限するシナリオは通常、21世紀にわたる[[:en:Carbon dioxide removal|二酸化炭素除去方法]]の大規模な使用を予測している。これらの技術への過度な依存とその環境影響について懸念がある。しかし、生態系の復元と土地利用転換の削減は、2030年までに最も排出量を削減できる緩和ツールの一つである。 | |||

陸上ベースの緩和策は、2022年のIPCCの緩和に関する報告書で「AFOLU緩和策」と呼ばれている。この略語は「農業、林業、その他の土地利用」を意味する。同報告書は、森林と生態系に関する関連活動からの経済的緩和可能性を次のように説明している。「森林およびその他の生態系(沿岸湿地、泥炭地、サバンナ、草原)の保全、管理の改善、および復元」。熱帯地域における森林伐採の削減には高い緩和可能性が見られる。これらの活動の経済的潜在力は、年間4.2〜7.4ギガトン(GtCO<sub>2</sub>-eq)と推定されている。 | |||

=== 森林 === | |||

== | {{Further/ja|:en:Carbon sequestration#Forestry|:en:Deforestation and climate change|:en:Reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation}} | ||

{{Further|Carbon sequestration#Forestry|Deforestation and climate change|Reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation}} | |||

====保全==== | |||

=== | {{Main/ja|:en:Deforestation#Control|:en:Proforestation|:en:Wildfire#Prevention}} | ||

{{Main|Deforestation#Control|Proforestation|Wildfire#Prevention}} | |||

[[File:Shennongjia virgin forest.jpg|thumb|先住民に[[:en:land rights|土地の権利]]を移転することは、森林を効率的に保全すると主張されている。]] | |||

[[File:Shennongjia virgin forest.jpg|thumb| | 2007年に発表された[[:en:Stern Review|スターン・レビュー]]は、森林破壊を抑制することが温室効果ガス排出量を削減するための非常に費用対効果の高い方法であると述べた。森林破壊の約95%は熱帯地域で発生しており、農業のための土地開墾が主な原因の一つである。一つの森林保全戦略は、土地に対する権利を公共所有から先住民に移転することである。土地の譲許はしばしば強力な採掘会社に与えられる。人間を排除し、さらには立ち退かせる[[:en:fortress conservation|要塞型保全]]と呼ばれる保全戦略は、しばしば土地のさらなる搾取につながる。これは、原住民が生き残るために採掘会社で働くようになるためである。 | ||

[[:en:Proforestation|プロフォレステーション]]は、森林がその生態学的潜在能力を最大限に発揮できるよう促進することである。放棄された農地に再成長した[[:en:secondary forest|二次林]]は、元の[[:en:old-growth forest|原生林]]よりも生物多様性が低いことが判明しており、これは緩和戦略となる。原生林はこれらの新しい森林よりも60%多くの炭素を貯蔵する。戦略には、[[:en:Rewilding (conservation biology)|リワイルディング]]や[[:en:wildlife corridor|野生生物回廊]]の設置が含まれる。 | |||

[[Proforestation]] | |||

====植林、再植林および砂漠化の防止==== | |||

= | {{Seealso/ja|:en:Desertification#Countermeasures}} | ||

{{Seealso|Desertification#Countermeasures}} | |||

[[:en:Afforestation|植林]]とは、以前に樹木がなかった場所に木を植えることである。最大4000万ヘクタール(Mha)(6300 x 6300 km)をカバーする新規植林のシナリオは、2100年までに900ギガトン以上の炭素(2300ギガトン{{CO2}})の累積炭素貯蔵を示唆している。しかし、これらの植林は、その規模があまりに大きいため、ほとんどの自然生態系を排除したり、食料生産を減少させたりすることになるため、積極的な排出削減の実行可能な代替策ではない。[[:en:Trillion Tree Campaign|一兆本の木キャンペーン]]はその一例である。しかし、生物多様性の保全も重要であり、例えば、すべての草地が森林への転換に適しているわけではない。草地は、[[:en:carbon sink|炭素吸収源]]から[[:en:carbon source|炭素排出源]]にさえ変わりうる。[[File:Coppice stool.jpg|thumb|right|長年森林伐採されてきた地域でも、既存の根や切り株を再生させる方が、植林よりも効率的であると主張されている。地元住民による樹木の法的所有権の欠如が、再成長を妨げる最大の障害である。]] | |||

[[Afforestation]] | |||

[[:en:Reforestation|再植林]]とは、既存の荒廃した森林や最近まで森林であった場所に再び木を植えることである。再植林は、年間少なくとも1ギガトンCO<sub>2</sub>を削減でき、その推定費用は1トンCO<sub>2</sub>あたり5〜15ドルである。世界中の劣化した森林すべてを復元すれば、約205ギガトン炭素(750ギガトンCO<sub>2</sub>)を吸収できる可能性がある。集約農業と都市化の進展に伴い、放棄された農地の量が増加している。一部の推定では、伐採された[[:en:old-growth forest|原生林]]1エーカーあたり、50エーカー以上の新しい[[:en:secondary forest|二次林]]が成長している。一部の国では、放棄された農地での再成長を促進することで、数年分の排出量を相殺できる可能性がある。 | |||

[[Reforestation]] | |||

新しい木を植えることは費用がかかり、リスクの高い投資となることがある。例えば、サヘル地域で植えられた木の約80%は2年以内に枯れてしまう。再植林は、植林よりも高い炭素貯蔵の可能性を秘めている。長年森林伐採されてきた地域でさえ、生きた根や切り株の「地下の森」が残っている。在来種の自然な発芽を助けることは、新しい木を植えるよりも安価であり、生存率も高い。これには、成長を促進するための[[:en:pruning|剪定]]や[[:en:coppicing|萌芽更新]]が含まれる。これはまた、薪炭材も提供し、そうでなければ森林破壊の主要な原因となる。このような[[:en:farmer-managed natural regeneration|農家主導型自然再生]]と呼ばれる慣行は何世紀も前から行われているが、実施における最大の障害は、樹木の所有権が国家にあることである。国家はしばしば材木権を企業に売却するため、地元住民は苗木を負債と見なし、引き抜いてしまう。マリやニジェールのような国での地元住民への法的援助や財産法の変更は、大きな変化をもたらした。科学者たちはこれらをアフリカにおける最大の肯定的な環境変革であると評している。法律が変わっていないナイジェリアのより不毛な土地との国境は、宇宙からでも識別可能である。 | |||

[[:en:Rangeland|放牧地]]は世界の土地の半分以上を占め、陸上炭素の35%を隔離できる可能性がある。牧畜民とは、しばしば[[:en:extensive farming|囲いのない放牧地]]で餌をとり移動する家畜の群れと共に移動する人々である。そのような土地は通常、他の種類の食料を栽培することができない。放牧地は大型の野生動物の群れと共進化してきたが、その多くは減少または絶滅しており、牧畜民の家畜の群れがそのような野生動物の群れに取って代わり、それによって生態系の維持に役立っている。しかし、広大な地域を広範囲にわたって移動する家畜の群れの動きは、政府によってますます制限されている。政府はしばしば、より収益性の高い用途のために土地に排他的な権利を与え、牧畜民をより囲まれた空間に制限している。これにより、土地の過放牧や砂漠化、そして[[:en:nomadic conflict|遊牧民の紛争]]が生じている。 | |||

[[Rangeland]] | |||

===土壌=== | |||

=== | {{Further/ja|:en:Carbon sequestration#Agriculture|:en:Carbon farming|}} | ||

{{Further|Carbon sequestration#Agriculture|Carbon farming|}} | |||

土壌炭素を増加させる多くの方法がある。これは複雑で、測定と計算が困難である。一つの利点は、例えば[[:en:Bioenergy with carbon capture and storage|BECCS]]や[[:en:afforestation|植林]]よりも、これらの方法におけるトレードオフが少ないことである。 | |||

< | 世界的に、健全な土壌を保護し、土壌炭素スポンジを回復させることで、年間76億トンの二酸化炭素を大気から除去できる可能性がある。これは米国の年間排出量よりも多い。樹木は地上で成長しながらCO<sub>2</sub>を捕捉し、地下により大量の炭素を[[:en:Plant root exudates|分泌]]する。樹木は土壌炭素スポンジの形成に貢献する。地表で形成された炭素は、木材が燃焼すると直ちにCO<sub>2</sub>として放出される。枯れ木が手付かずのまま残された場合、分解が進むにつれて炭素の一部のみが大気中に戻る。 | ||

</ | |||

農業は土壌炭素を枯渇させ、土壌を生命を維持できない状態にする可能性がある。しかし、[[:en:conservation farming|保全農業]]は土壌中の炭素を保護し、時間をかけて損傷を修復できる。被覆作物の農法は炭素農業の一形態である。土壌中の炭素隔離を高める方法には、[[:en:no-till farming|不耕起栽培]]、残渣マルチング、輪作などがある。科学者たちは、土壌有機炭素を増加させるためのヨーロッパの土壌に対する最良の管理方法を記述している。これらは、耕作地から牧草地への転換、藁の投入、耕うんの削減、耕うんの削減と藁の投入の組み合わせ、[[:en:Ley farming|休閑作物]]システム、被覆作物である。 | |||

もう一つの緩和策は、[[:en:biochar|バイオ炭]]の生産と土壌への貯蔵である。これはバイオマスの熱分解後に残る固形物質である。バイオ炭の生産は、バイオマスからの炭素の半分を大気中に放出するかCCSで捕捉し、残りの半分を安定したバイオ炭中に保持する。それは土壌中で数千年持続できる。バイオ炭は[[:en:acidic soil|酸性土壌]]の[[:en:soil fertility|土壌肥沃度]]を高め、[[:en:agricultural productivity|農業生産性]]を向上させる可能性がある。バイオ炭の生産中には熱が放出され、これは[[:en:bioenergy|バイオエネルギー]]として利用できる。 | |||

=== 湿地 === | |||

== | {{Further/ja|:en:Carbon sequestration#Wetlands|:en:Wetland#Climate change mitigation}} | ||

{{Further|Carbon sequestration#Wetlands|Wetland#Climate change mitigation}} | |||

湿地の復元は重要な緩和策である。限られた土地面積で中程度から高い緩和潜在力があり、トレードオフとコストが低い。湿地は気候変動に関して2つの重要な機能を果たす。それらは[[:en:Carbon sink|炭素を隔離]]し、光合成によって二酸化炭素を固体の植物材料に変換する。また、水を貯蔵し、調節する。湿地は世界的に年間約4500万トンの炭素を貯蔵している。 | |||

一部の[[:en:Wetland methane emissions|湿地はメタン排出の重要な発生源]]である。また、一部は亜酸化窒素も排出する。泥炭地は世界的に陸地の表面のわずか3%を占めるに過ぎない。しかし、最大550ギガトン(Gt)の炭素を貯蔵している。これは全ての土壌炭素の42%を占め、世界の森林を含む他の全ての植生タイプに貯蔵されている炭素を超えている。泥炭地への脅威には、農業のための土地の排水が含まれる。もう一つの脅威は、木材を伐採することであり、木々は泥炭地を保持し固定するのに役立つ。さらに、泥炭はしばしば堆肥として販売される。泥炭地の排水路を塞ぎ、自然植生が回復するのを許すことで、劣化した泥炭地を復元することが可能である。 | |||

[[:en:Mangrove|マングローブ]]、[[:en:salt marsh|塩性湿地]]、[[:en:seagrass|アマモ]]は、海洋の植生生息地の大部分を構成している。それらは陸上の植物バイオマスのわずか0.05%に過ぎない。しかし、熱帯林よりも40倍速く炭素を貯蔵する。[[:en:Bottom trawling|底引き網漁]]、沿岸開発のための[[:en:dredging|浚渫]]、[[:en:fertiliser runoff|肥料流出]]は沿岸生息地を損傷させている。特筆すべきことに、過去2世紀で世界の[[:en:oyster reef|カキ礁]]の85%が除去された。カキ礁は水を浄化し、他の種の繁殖を助ける。これにより、その地域のバイオマスが増加する。さらに、カキ礁はハリケーンの波の力を弱めることで気候変動の影響を緩和する。また、海面上昇による[[浸食]]も軽減する。沿岸湿地の復元は、内陸湿地の復元よりも費用対効果が高いと考えられている。 | |||

[[Mangrove]] | |||

=== 深海 === | |||

== | {{Further/ja|:en:Carbon sequestration#Sequestration techniques in oceans|:en:Ocean acidification#Technologies to remove carbon dioxide from the ocean|:en:Blue carbon}} | ||

{{Further|Carbon sequestration#Sequestration techniques in oceans|Ocean acidification#Technologies to remove carbon dioxide from the ocean|Blue carbon}} | |||

これらの選択肢は、海洋貯留層が貯蔵できる炭素に焦点を当てている。これには、[[:en:ocean fertilization|海洋肥沃化]]、[[:en:ocean alkalinity enhancement|海洋アルカリ化促進]]、または[[:en:enhanced weathering|強化風化]]が含まれる。IPCCは2022年に、海洋ベースの緩和策は現在、限定的な展開可能性しか持たないと判断した。しかし、将来の緩和潜在力は大きいと評価した。合計で、海洋ベースの方法は年間1〜100ギガトンのCO<sub>2</sub>を除去できる可能性があると判断した。そのコストは1トンCO<sub>2</sub>あたり40〜500米ドル程度である。これらの選択肢のほとんどは、[[:en:ocean acidification|海洋酸性化]]の削減にも役立つ可能性がある。これは、大気中のCO<sub>2</sub>濃度増加によって引き起こされるpH値の低下である。 | |||

[[:en:whale|クジラ]]の個体数回復は緩和において役割を果たす可能性がある。なぜならクジラは海洋の[[:en:nutrient recycling|栄養塩循環]]において重要な役割を果たすからである。これは、クジラの液体糞が海洋表面に留まる「[[:en:whale pump|クジラポンプ]]」と呼ばれるものを通じて起こる。[[:en:Phytoplankton|植物プランクトン]]は太陽光を利用して光合成を行うために海洋表面近くに生息しており、糞中の多くの炭素、窒素、鉄に依存している。植物プランクトンが[[:en:marine food chain|海洋食物連鎖]]の[[:en:Primary production|基盤]]を形成するため、これにより海洋[[バイオマス]]が増加し、それに伴い海洋に隔離される炭素量も増加する。 | |||

ブルーカーボン管理は、海洋ベースの生物学的[[:en:carbon dioxide removal|二酸化炭素除去]](CDR)のもう一つのタイプである。これは陸上および海洋ベースの対策を含むことができる。この用語は通常、潮汐湿地、[[:en:mangrove|マングローブ]]、[[:en:seagrass|アマモ]]が炭素隔離において果たす役割を指す。これらの取り組みの一部は、海洋炭素の大部分が保持されている深海でも行うことができる。これらの生態系は気候変動緩和に貢献できるだけでなく、[[:en:ecosystem-based adaptation|生態系ベースの適応]]にも貢献する。逆に、ブルーカーボン生態系が劣化または失われると、炭素が大気中に放出される。ブルーカーボン潜在力の開発への関心が高まっている。科学者たちは、場合によってはこれらのタイプの生態系が陸上林よりもはるかに多くの炭素を単位面積あたり除去することを発見している。しかし、炭素除去ソリューションとしてのブルーカーボンの長期的な有効性については議論が続いている。 | |||

===強化風化=== | |||

== | {{Main/ja|:en:Enhanced weathering}} | ||

{{Main|Enhanced weathering}} | |||

強化風化は、年間20億から40億トンのCO2を除去できる可能性を秘めた技術である。このプロセスは、天然の[[:en:weathering|風化]]を加速させることを目的としている。 | |||

具体的には、[[:en:basalt|玄武岩]]のような細かく砕かれた[[:en:Silicate mineral|ケイ酸塩鉱物]]を地表に散布する。これにより、岩石、水、空気の間の化学反応が促進される。この反応を通じて、大気中の[[:en:Carbon dioxide removal|二酸化炭素が除去]]され、最終的に固体の[[:en:carbonate mineral|炭酸塩鉱物]]または海洋の[[:en:alkalinity|アルカリ度]]として永久的に貯蔵される。 | |||

== CO<sub>2</sub>を回収・貯蔵するその他の方法{{Anchor|:en:Other methods to capture and store CO2}} == | |||

{{Main/ja|:en:Direct air capture|:en:Carbon capture and storage|:en:Bioenergy with carbon capture and storage}} | |||

{{Main|Direct air capture|Carbon capture and storage|Bioenergy with carbon capture and storage}} | |||

[[File:Carbon sequestration-2009-10-07.svg|thumb|upright=1.35|大規模な点源、例えば天然ガスの燃焼からの二酸化炭素排出の陸上および地質学的隔離を示す模式図]] | |||

[[File:Carbon sequestration-2009-10-07.svg|thumb|upright=1.35| | |||

大気中の二酸化炭素(CO<sub>2</sub>)を除去する伝統的な陸上ベースの方法に加えて、他の技術も開発中である。これらはCO<sub>2</sub>排出量を削減し、既存の大気中CO<sub>2</sub>濃度を低下させる可能性がある。[[:en:Carbon capture and storage|炭素回収・貯留]](CCS)は、セメント工場や[[:en:Bioenergy with carbon capture and storage|バイオマス]]発電所などの大規模な[[:en:Point source pollution|点源]]からCO<sub>2</sub>を回収し、大気中に放出せずに安全に貯蔵することで気候変動を緩和する方法である。IPCCは、CCSなしでは地球温暖化を食い止めるコストが倍増すると推定している。 | |||

</ | |||

< | 太陽放射管理とともに検討されている最も有望な二酸化炭素除去方法の中でも、バイオ炭土壌改良はすでに商業的に展開されている。研究によると、バイオ炭に含まれる炭素は土壌中で数世紀にわたって安定しており、年間ギガトンのCO<sub>2</sub>を除去する持続的な潜在力がある。専門家の評価では、バイオ炭によるCO<sub>2</sub>除去の正味費用は1トンあたり30〜120米ドルである。市場データによると、2023年に供給された耐久性のある炭素除去クレジットの94%がバイオ炭によるものであり、現在の拡張性を示している。一方、成層圏エーロゾル注入(SAI)は、成層圏に硫酸塩エーロゾルを散布することで地球の温度を迅速に低下させる可能性がある。しかし、気候変動に関連する規模での展開には、新しい高高度航空機の設計と認証が必要であり、そのプロセスには10年以上かかると推定され、冷却温度1度あたり年間約180億米ドルの継続的な運用コストがかかる。モデルはSAIが地球の平均気温を低下させることを確認しているが、オゾン層破壊、地域的な降水パターンの変化、プログラムが中断された場合の突然の「[[:en:termination shock|終端ショック]]」による温暖化のリスクなど、潜在的な副作用がある。これらの全身的なリスクはバイオ炭の展開にはない。 | ||

[[:en:Bioenergy with carbon capture and storage|バイオエネルギーと炭素回収・貯蔵]](BECCS)は、CCSの潜在能力を拡張し、大気中CO<sub>2</sub>濃度を低下させることを目的としている。このプロセスは、バイオエネルギーのために栽培されたバイオマスを使用する。バイオマスは、燃焼、発酵、または熱分解によるバイオマスの消費を通じて、電力、熱、バイオ燃料などの有用な形態のエネルギーを生成する。このプロセスは、バイオマスが成長する際に大気から取り込まれたCO<sub>2</sub>を回収する。その後、地下に貯蔵するか、バイオ炭として土地に適用する。これにより、[[:en:Carbon dioxide removal|大気から効果的に除去]]される。これはBECCSを[[:en:Negative emissions technology|負の排出技術]](NET)にする。 | |||

[[Bioenergy with carbon capture and storage]] | |||

科学者たちは2018年にBECCSからの負の排出量の潜在的な範囲を年間0〜22ギガトンと推定した。2022年時点で、BECCSは年間約200万トンのCO<sub>2</sub>を回収していた。バイオマスのコストと入手可能性がBECCSの広範な展開を制限している。BECCSは現在、[[:en:Integrated assessment modelling|統合評価モデル]](IAM)など、IPCCプロセスに関連するモデリングにおいて、2050年以降の気候目標達成の大部分を占めている。しかし、生物多様性の損失のリスクがあるため、多くの科学者は懐疑的である。 | |||

[[:en:Direct air capture|直接空気回収]]は、周囲の空気から直接CO<sub>2</sub>を回収するプロセスである。これは、点源から炭素を回収するCCSとは対照的である。それは、[[:en:Carbon sequestration|隔離]]、[[:en:Carbon capture and utilization|利用]]、または[[:en:carbon-neutral fuel|カーボンニュートラル燃料]]や[[:en:windgas|ウィンドガス]]の生産のために濃縮されたCO<sub>2</sub>の流れを生成する。 | |||

[[Direct air capture]] | |||

</ | |||

== セクター別緩和{{Anchor|Mitigation by sector}} == | |||

== Mitigation by sector == | {{See also/ja|:en:Greenhouse gas emissions#Emissions by sector}} | ||

{{See also|Greenhouse gas emissions#Emissions by sector}} | {{Imageright| | ||

{{multiple image | {{multiple image | ||

| total_width | | total_width = 500 | ||

| image1 | | image1 = Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Economic Sector.svg | ||

| caption1 | | caption1 = 直接排出と間接排出を考慮すると、産業は世界の排出量の中で最も高い割合を占めるセクターである。 | ||

| image2 | | image2 = Global GHG Emissions by Sector 2016.png | ||

| caption2 | | caption2 = 2016年におけるセクター別の世界の温室効果ガス排出量。パーセンテージは、すべての京都議定書対象温室効果ガスの推定世界排出量から、CO<sub>2</sub>換算量(GtCO<sub>2</sub>e)に変換して計算されている。 | ||

}} | }}}} | ||

=== 建物 === | |||

=== | {{Further/ja|:en:Energy-efficient buildings|:en:Sustainable architecture|:en:Green building|:en:Low-energy house|:enAir conditioning paradox}} | ||

{{Further|Energy-efficient buildings|Sustainable architecture|Green building|Low-energy house| | |||

建築部門は世界のエネルギー関連{{CO2}}排出量の23%を占める。エネルギーの約半分は暖房と給湯に使われている。建物の断熱は、一次エネルギー需要を大幅に削減できる。[[:en:Heat pump|ヒートポンプ]]の負荷は、変動性再生可能エネルギー源を系統に統合するためのデマンドレスポンスに参加できる柔軟な資源も提供する可能性がある。[[:en:Solar water heating|太陽熱温水器]]は熱エネルギーを直接利用する。充足策には、世帯のニーズの変化に応じてより小さな家に移ること、空間の複合利用、機器の共有利用などがある。計画者や土木工学者は、パッシブソーラー建築設計、低エネルギー建築、またはゼロエネルギー建築技術を使用して新しい建物を建設できる。さらに、都市部の開発において、より明るい色で反射率の高い材料を使用することで、よりエネルギー効率良く冷房できる建物を設計することが可能である。 | |||

ヒートポンプは建物を効率的に暖房し、空調によって冷房する。現代のヒートポンプは通常、消費される電気エネルギーの約3〜5倍の熱エネルギーを輸送する。その量は成績係数と外気温に依存する。 | |||

冷凍と空調は、化石燃料ベースのエネルギー生産とフッ素化ガスの使用によって引き起こされる世界の{{CO2}}排出量の約10%を占める。パッシブクーリング建築設計や[[:en:passive daytime radiative cooling|受動型日中放射冷却]]表面などの代替冷却システムは、空調の使用を削減できる。暑く乾燥した気候の郊外や都市は、日中放射冷却により冷房からのエネルギー消費を大幅に削減できる。 | |||

< | 貧しい国々での熱の上昇と機器の普及により、冷房のためのエネルギー消費量は大幅に増加する可能性が高い。世界で最も暑い地域に住む28億人のうち、現在エアコンを所有しているのはわずか8%に過ぎないが、米国と日本では90%の人が所有している。エネルギー効率の改善と、空調のための電力の脱炭素化を、超汚染性の冷媒からの転換と組み合わせることで、世界は今後40年間で累積的に最大210〜460 GtCO<sub>2</sub>-eqの温室効果ガス排出量を回避できる可能性がある。冷却部門における再生可能エネルギーへの移行には2つの利点がある。日中にピークを迎える太陽エネルギー生産は冷却に必要な負荷と一致し、さらに、冷却は電力系統における負荷管理の大きな可能性を秘めている。 | ||

</ | |||

=== 都市計画 === | |||

{{Main/ja|:en:Climate change and cities}} | |||

{{Main|Climate change and cities}} | |||

[[File:BikesInAmsterdam 2004 SeanMcClean.jpg|right|thumb|[[:en:Bicycle|自転車]]は[[:en:carbon footprint|カーボンフットプリント]]がほとんどない。]] | |||

[[File:BikesInAmsterdam 2004 SeanMcClean.jpg|right|thumb|[[Bicycle]] | |||

都市は2020年に、商品やサービスの生産と消費から発生するCO<sub>2</sub>と{{CH4}}を合わせて28ギガトン(GtCO<sub>2</sub>-eq)排出した。[[:en:Climate-smart city|気候スマートな]]都市計画は、移動距離を減らすために[[:en:urban sprawl|都市の無秩序な拡大]]を抑制することを目指している。これにより、輸送からの排出量が削減されます。歩行可能性と[[:en:cycling infrastructure|自転車インフラ]]を改善して自動車から切り替えることは、国全体の経済にとって有益である。 | |||

[[:en:Urban forestry|都市林業]]、湖、その他のブルー・グリーンインフラは、冷房のエネルギー需要を削減することで、直接的および間接的に排出量を削減できる。[[:en:municipal solid waste|都市固形廃棄物]]からのメタン排出量は、分別、[[:en:compost|堆肥化]]、リサイクルによって削減できる。 | |||

[[Urban forestry]] | |||

=== 輸送 === | |||

=== | {{Main/ja|:en:Sustainable transport|:en:Phase-out of fossil fuel vehicles}} | ||

{{Main|Sustainable transport|Phase-out of fossil fuel vehicles}} | |||

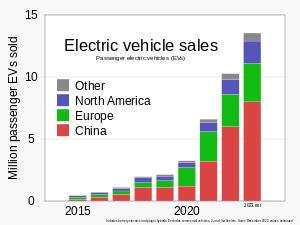

[[File:2015- Passenger electric vehicle (EV) annual sales - BloombergNEF.svg|thumb|電気自動車(EV)の販売は、温室効果ガスを排出するガソリン車からの移行傾向を示している。]] | |||

[[File:2015- Passenger electric vehicle (EV) annual sales - BloombergNEF.svg|thumb| | [[輸送]]は世界の排出量の15%を占めている。公共交通機関、低炭素貨物輸送、および[[:en:cycling|自転車]]の利用を増やすことは、輸送の脱炭素化の重要な要素である。 | ||

[[:en:Electric vehicle|電気自動車]]と環境に優しい鉄道は、化石燃料の消費を削減するのに役立つ。ほとんどの場合、電気鉄道は航空輸送やトラック輸送よりも効率的である。その他の効率化手段には、公共交通機関の改善、スマートモビリティ、カーシェアリング、[[:en:hybrid vehicle|電気ハイブリッド車]]などがある。乗用車の化石燃料は排出量取引に含めることができる。さらに、自動車に支配された輸送システムから、低炭素の先進的な公共交通システムへと移行することが重要である。 | |||

[[Electric vehicle]] | |||

重量があり大型の自家用車(自動車など)は、移動に多くのエネルギーを必要とし、都市空間を大きく占める。これらを代替するいくつかの交通手段が利用可能である。欧州連合は[[:en:European Green Deal|欧州グリーンディール]]の一環としてスマートモビリティを位置づけている。[[:en:Smart city|スマートシティ]]においても、スマートモビリティは重要である。[[File:Societe de transport de Montreal bus 36-902 - 08.jpg|thumb|モントリオールの[[:en:Battery electric bus|電気バス]]]] | |||

世界銀行は、低所得国が電気バスを購入するのを支援している。購入価格はディーゼルバスよりも高いが、運行コストの低さや、空気がきれいになることによる健康改善が、この高い価格を相殺することができる。 | |||

2050年までに、走行中の自動車の4分の1から4分の3が電気自動車になると予測されている。水素は、バッテリーだけでは重すぎる場合、長距離の大型貨物トラックの解決策となる可能性がある。 | |||

==== 船舶 ==== | |||

= | {{Further/ja|:en:Environmental effects of shipping#Greenhouse gas emissions}} | ||

{{Further|Environmental effects of shipping#Greenhouse gas emissions}} | |||

海運業界では、[[:en: liquefied natural gas|液化天然ガス]](LNG)を船舶用燃料として使用することが、排出規制によって推進されている。船舶運航者は、[[:en:heavy fuel oil|重油]]からより高価な石油系燃料に切り替えるか、高価な排ガス処理技術を導入するか、[[:en:Marine LNG Engine|LNGエンジン]]に切り替える必要がある。メタンがエンジンを通して未燃焼のまま漏れるメタンすべりは、LNGの利点を低下させる。世界最大のコンテナ輸送会社であり船舶運航会社であるマースクは、LNGのような移行期の燃料への投資における[[:en:stranded asset|座礁資産]]について警告している。同社は、グリーンアンモニアを将来の好ましい燃料タイプの一つとして挙げている。同社は、カーボンニュートラルなメタノールで稼働する初のカーボンニュートラルな船舶を2023年までに就航させると発表した。クルーズ客船運航会社は、部分的に[[:en:hydrogen-powered ship|水素動力船]]を試験運用している。 | |||

ハイブリッドおよび全電動フェリーは短距離に適している。ノルウェーの目標は、2025年までに全電動船隊とすることである。 | |||

==== 航空輸送 ==== | |||

==== | {{Further/ja|:en:environmental impact of aviation}} | ||

{{Further|environmental impact of aviation}} | [[File:CO2 emissions fraction of Aviation (%25).png|thumb|1940年から2018年の間に、航空からの[[:en:CO2 emissions|CO<sub>2</sub>排出量]]は、全CO<sub>2</sub>排出量の0.7%から2.65%に増加した。]] | ||

[[File:CO2 emissions fraction of Aviation (%25).png|thumb| | |||

ジェット旅客機は、二酸化炭素、窒素酸化物、[[:en:Condensation trails|飛行機雲]]、粒子状物質を排出することで気候変動に寄与している。それらの放射強制力は、{{CO2}}単独の場合の1.3〜1.4倍と推定されており、誘発される巻雲は含まれていない。2018年には、世界の商業運航が全CO2排出量の2.4%を生成した。 | |||

航空業界は燃費効率を向上させてきたが、航空輸送量が増加したため、総排出量は増加している。2020年までに、航空排出量は2005年よりも70%高く、2050年までに300%増加する可能性がある。 | |||

航空の環境フットプリントは、[[:en:fuel economy in aircraft|航空機の燃料効率]]を向上させることで削減できる。窒素酸化物、粒子状物質、飛行機雲による非{{CO2}}気候影響を低減するために、飛行ルートを最適化することも役立つ。[[:en:Aviation biofuel|航空バイオ燃料]]、[[:en:carbon emission trading|炭素排出権取引]]、[[:en:carbon offsetting|炭素オフセット]](191カ国が参加するICAOの[[:en:Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation|国際航空のためのカーボンオフセットおよび削減スキーム]](CORSIA)の一部)は、CO2排出量を削減できる。[[:en:Short-haul flight ban|短距離飛行禁止]]、鉄道接続、個人的な選択、[[:en:aviation taxation and subsidies|航空機への課税と補助金]]は、フライト数を減らすことにつながる。[[:en:Hybrid electric aircraft|ハイブリッド電気航空機]]や[[:en:electric aircraft|電気航空機]]、または[[:en:hydrogen-powered aircraft|水素動力航空機]]が化石燃料動力航空機に取って代わる可能性がある。 | |||

専門家は、航空からの排出量が、少なくとも2040年まではほとんどの予測で増加すると予想している。これらは現在、{{CO2}}換算で180Mt、または輸送排出量の11%に相当する。航空バイオ燃料と水素は、今後数年間でごく一部のフライトしかカバーできない。専門家は、ハイブリッド駆動航空機が2030年以降に商業地域定期便を開始すると予想している。バッテリー駆動航空機は2035年以降に市場に投入される可能性が高い。CORSIAの下では、運航会社は2019年レベルを超える排出量をカバーするために[[:en:carbon offset|炭素オフセット]]を購入できる。CORSIAは2027年から義務化される。 | |||

===農業、林業、土地利用=== | |||

[[File:Environmental-impact-of-food-by-life-cycle-stage.png|thumb|upright=1.35|異なる食品のサプライチェーン全体における温室効果ガス排出量。緩和の観点から推奨される食品と推奨されない食品を示している。]] | |||

[[File:Environmental-impact-of-food-by-life-cycle-stage.png|thumb|upright=1.35| | {{See also/ja|:en:Greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture|:en:Environmental impact of meat production|:en:Sustainable agriculture}} | ||

{{See also|Greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture|Environmental impact of meat production| | |||

温室効果ガス排出量のほぼ20%は農業と林業部門から発生している。これらの排出量を大幅に削減するには、農業部門への年間投資額を2030年までに2600億ドルに増やす必要がある。これらの投資による潜在的利益は2030年までに4.3兆ドルと推定されており、16対1という実質的な経済的リターンをもたらす。 | |||

フードシステムにおける緩和策は、4つのカテゴリーに分けられる。これらは需要側の変化、生態系保護、農場での緩和、および[[:en:supply chains|サプライチェーン]]における緩和である。需要側では、[[:en:food waste|食品廃棄物]]を制限することが食品排出量を削減する効果的な方法である。[[:en:plant-based diets|植物ベースの食事]]など、動物性食品への依存度が低い食事への変更も効果的である。 | |||

世界のメタン排出量の21%を占める牛は、地球温暖化の主要な要因である。熱帯雨林が伐採され、土地が放牧用に転換されると、その影響はさらに大きくなる。ブラジルでは、牛肉1kgの生産により最大335kgのCO<sub>2</sub>換算排出量が生じる可能性がある。 | |||

他の家畜、糞尿管理、稲作も、農業における化石燃料燃焼に加えて温室効果ガスを排出する。 | |||

家畜からの温室効果ガス排出量を削減するための重要な緩和策には、遺伝子選抜、[[:en:Methanotroph|メタン酸化細菌]]の第一胃への導入、飼料の変更、放牧管理などがある。その他の選択肢としては、[[ruminant/ja|反芻動物]]を含まない代替品、例えば[[milk substitute/ja|植物性ミルク]]や[[meat analogue/ja|代替肉]]への食事の変更がある。家禽のような非反芻動物の家畜は、はるかに少ない温室効果ガスを排出する。 | |||

稲作におけるメタン排出量は、水管理の改善、乾燥種まきと一度の排水の組み合わせ、または[[:en:alternate wetting and drying|間断灌漑]]を実行することによって削減可能である。これにより、湛水と比較して最大90%の排出量削減が可能となり、収量も増加する。 | |||

[[nutrient management/ja|栄養管理]]を通じて[[Fertilizer/ja#Nitrogen_fertilizers|窒素肥料]]の使用を削減することで、2020年から2050年までに2.77〜11.48ギガトンの二酸化炭素に相当する亜酸化窒素排出量を回避できる可能性がある。 | |||

=== 産業 === | |||

{{Pie chart | {{Pie chart | ||

| caption= | | caption= 2023年国毎の[[:en:List of countries by carbon dioxide emissions|二酸化炭素排出量]] | ||

| other = yes | | other = yes | ||

| label1 = | | label1 = 中国 | ||

| value1 = 31.8 | color1=#E33 | | value1 = 31.8 | color1=#E33 | ||

| label2 = | | label2 = 米国 | ||

| value2 = 14.4 | color2=#1A9 | | value2 = 14.4 | color2=#1A9 | ||

| label3 = | | label3 = EU | ||

| value3 = 4.9 | color3=#36A | | value3 = 4.9 | color3=#36A | ||

| label4 = | | label4 = インド | ||

| value4 = 9.5 | color4=#CC5 | | value4 = 9.5 | color4=#CC5 | ||

| label5 = | | label5 = ロシア | ||

| value5 = 5.8 | color5=#E72 | | value5 = 5.8 | color5=#E72 | ||

| label6 = | | label6 = 日本 | ||

| value6 = 3.5 | color6=#928 | | value6 = 3.5 | color6=#928 | ||

}} | }} | ||

直接排出と間接排出を含めると、産業は[[温室効果ガス]]の最大の排出源である。[[:en:Electrification|電化]]は産業からの排出量を削減できる。電力が選択肢とならない[[:en:energy-intensive industries|エネルギー多消費産業]]においては、[[:en:Green hydrogen|グリーン水素]]が主要な役割を果たすことができる。さらなる緩和策としては、鉄鋼業やセメント産業がより汚染の少ない生産プロセスに切り替えることが挙げられる。排出原単位を削減するために製品をより少ない材料で作ることができ、産業プロセスをより効率的にすることもできる。最後に、[[:en:circular economy|循環経済]]の措置は新規材料の必要性を減らす。これは、それらの材料の採掘や収集から放出されていたであろう排出量も削減する。 | |||

セメント生産の脱炭素化には新しい技術が必要であり、したがってイノベーションへの投資が必要である。しかし、緩和のための技術はまだ成熟していない。そのため、少なくとも短期的にはCCSが必要となるだろう。 | |||

もう一つの大きなカーボンフットプリントを持つセクターは鉄鋼業であり、世界の排出量の約7%を占めている。排出量は、[[:en:electric arc furnaces|電弧炉]]を使用してスクラップ鋼を溶融しリサイクルすることで削減できる。排出なしでバージンスチールを生産するには、[[:en:blast furnace|高炉]]を水素[[:en:direct reduced iron|直接還元鉄]]と[[:en:electric arc furnace|電弧炉]]に置き換えることができる。あるいは、炭素回収・貯留ソリューションを使用することも可能である。 | |||

石炭、天然ガス、石油の生産には、しばしば重大なメタン漏洩が伴う。2020年代初頭、一部の政府はこの問題の規模を認識し、規制を導入した。油井やガス井、処理施設における[[:en:Methane leaks|メタン漏洩]]は、ガスを国際的に容易に取引できる国では費用対効果の高い解決策である。イランやトルクメニスタンなどガスが安価な国では漏洩が発生している。そのほとんどは、古い部品の交換や定常的なフレアリングの防止によって止めることができる。[[:en:Coalbed methane|炭層メタン]]は、炭鉱が閉鎖された後でも漏洩し続ける可能性がある。しかし、それは排水や換気システムによって回収することができる。化石燃料企業は、メタン漏洩に対処するための財政的インセンティブを常に持っているわけではない。 | |||

== コベネフィット == | |||

= | 気候変動緩和のコベネフィットは、「付随的便益」とも呼ばれ、科学文献では当初、温室効果ガス排出量の削減がいかに大気質を改善し、その結果、人間の健康に良い影響を与えるかについて記述した研究が主流であった。コベネフィット研究の範囲は、その経済的、社会的、生態学的、政治的意味合いにまで拡大した。 | ||

気候緩和および[[:en:climate change adaptation|適応策]]から生じるポジティブな二次的効果は、1990年代から研究で言及されてきた。IPCCは2001年に初めてコベネフィットの役割に言及し、その後の第4次および第5次評価サイクルでは、労働環境の改善、廃棄物の削減、健康上の利益、設備投資の削減を強調した。 | |||

IPCCは2007年に「温室効果ガス緩和のコベネフィットは、政策立案者が行う分析において重要な決定基準となりうるが、しばしば無視されている」と指摘し、コベネフィットは「企業や意思決定者によって、定量化、貨幣化、あるいは特定さえされていない」と付け加えた。コベネフィットを適切に考慮することで、「緩和行動のタイミングとレベルに関する政策決定に大いに影響を与える」ことができ、「国民経済と技術革新に大きな利益がある」可能性がある。 | |||

英国における気候変動対策の分析では、公衆衛生上の利益が、気候変動対策から得られる総利益の主要な構成要素であることが判明した。 | |||

=== 雇用と経済発展 === | |||

== | {{See also/ja|:en:Renewable energy#Market and industry trends}} | ||

{{See also|Renewable energy#Market and industry trends}} | コベネフィットは、雇用、産業発展、国家のエネルギー独立性、および[[自家消費]]に良い影響を与える可能性がある。再生可能エネルギーの導入は、雇用機会を育成できる。国や導入シナリオにもよるが、石炭火力発電所を再生可能エネルギーに置き換えることで、平均MWあたりの雇用数を2倍以上に増やすことができる。特に太陽エネルギーと風力エネルギーへの再生可能エネルギーへの投資は、生産の価値を高めることができる。エネルギー輸入に依存している国々は、再生可能エネルギーを導入することでエネルギー独立性を高め、供給安定性を確保できる。再生可能エネルギーからの国内エネルギー生産は化石燃料輸入の需要を低下させ、年間の経済的節約を拡大する。 | ||

欧州委員会は、2030年までに水素生産で18万人、太陽光発電で6万6千人の熟練労働者の不足を予測している。 | |||

=== エネルギー安全保障 === | |||

再生可能エネルギーのシェアを高めることは、さらに[[:en:energy security|エネルギー安全保障]]を高めることにつながる。農村部におけるエネルギーアクセスや農村部の生計改善など、社会経済的コベネフィットが分析されている。完全に電化されていない農村部は、[[:en:renewable energy|再生可能エネルギー]]の導入から恩恵を受けることができる。太陽光発電によるミニグリッドは、経済的に存続可能で、費用対効果が高く、停電の回数を減らすことができる。エネルギーの信頼性には追加的な社会的な影響がある。安定した電力は教育の質を向上させる。 | |||

国際エネルギー機関([[:en:International Energy Agency|IEA]])は[[:en:Efficient energy use|エネルギー効率]]の「多重便益アプローチ」を明示し、国際再生可能エネルギー機関([[:en:International Renewable Energy Agency|IRENA]])は再生可能エネルギー部門のコベネフィットのリストを具体化した。 | |||

===健康と福祉=== | |||

== | {{Further/ja|:en:Effects of climate change on human health#Benefits from climate change mitigation and adaptation}} | ||

{{Further|Effects of climate change on human health#Benefits from climate change mitigation and adaptation}} | {{See also/ja|:en:Health and environmental impact of the coal industry|:en:Health and environmental impact of the petroleum industry}} | ||

{{See also|Health and environmental impact of the coal industry|Health and environmental impact of the petroleum industry}} | |||

気候変動緩和による健康上の利益は大きい。潜在的な対策は、気候変動による将来の健康影響を緩和するだけでなく、直接的に健康を改善することもできる。気候変動緩和は、[[:en:air pollution|大気汚染]]の削減など、様々な健康上のコベネフィットと相互に関連している。化石燃料燃焼によって発生する大気汚染は、地球温暖化の主要な要因であると同時に、年間多数の死者の原因でもある。一部の推定では、2018年には{{tooltip|2=これの再評価と、死亡者数ではなく死亡への寄与という観点からの死亡率影響のより繊細な評価が必要かもしれない|870万人}}もの過剰死があったとされる。2023年の研究では、心臓発作、脳卒中、慢性閉塞性肺疾患などの病気を引き起こすことで、2019年時点で化石燃料が毎年500万人以上の命を奪っていると推定されている。[[:en:Particulate pollution|粒子状大気汚染]]が圧倒的に多くの死者を出し、次いで[[:en:ground-level ozone|地上オゾン]]が続く。 | |||

緩和政策は、赤身肉の少ないより健康的な食事、より活動的なライフスタイル、都市の緑地への接触機会の増加なども促進できる。都市の緑地へのアクセスはメンタルヘルスにも利益をもたらす。[[:en:Green infrastructure|グリーンインフラ]]と[[:en:Blue space|ブルーインフラ]]の利用増加は、[[都市のヒートアイランド現象]]を軽減できる。これにより、人々の[[:en:Hyperthermia|熱ストレス]]が軽減される。 | |||

===気候変動適応=== | |||

== | {{Further/ja|:en:Climate change adaptation#Co-benefits with mitigation}} | ||

{{Further|Climate change adaptation#Co-benefits with mitigation}} | 一部の緩和策は、[[:en:climate change adaptiation|気候変動適応]]の分野でコベネフィットを持つ。これは、例えば多くの[[:en:Nature-based Solutions|自然を活用した解決策]]の場合に当てはまる。都市の文脈での例としては、緩和と適応の両方の利益を提供する都市のグリーン・ブルーインフラが含まれる。これは、[[:en:Urban forestry|都市林]]や街路樹、[[:en:green roof|緑化屋根]]、[[:en:Green wall|壁面緑化]]、[[:en:urban agriculture|都市農業]]などの形をとることができる。緩和は、炭素吸収源の保全と拡大、および建物のエネルギー使用量の削減によって達成される。適応の利益は、例えば熱ストレスの軽減や洪水リスクの軽減によってもたらされる。 | ||

[[File:Carbon taxes and emission trading worldwide.svg|alt=世界中の炭素税と排出権取引|thumb|upright=1.35|世界における排出量取引と炭素税 (2019) | |||

[[File:Carbon taxes and emission trading worldwide.svg|alt= | {{Legend|#009a3e|[[:en:Carbon emission trading|排出量取引]]実施済みまたは予定}} | ||

{{Legend|#009a3e|[[Carbon emission trading]] | {{Legend|#323b90|[[:en:Carbon tax|炭素税]]実施済みまたは予定}} | ||

{{Legend|#323b90|[[Carbon tax]] | {{Legend|#fbba00|[[:en:Carbon emission trading|排出量取引]]または[[:en:carbon tax|炭素税]]検討中}}]] | ||

{{Legend|#fbba00|[[Carbon emission trading]] | |||

== 負の副作用{{Anchor|Negative side effects}} == | |||

== Negative side effects == | 緩和策は、負の副作用とリスクを伴うこともある。農業と林業において、緩和策は生物多様性や生態系の機能に影響を与える可能性がある。再生可能エネルギーにおいては、金属や鉱物の採掘が保護地域への脅威を増加させる可能性がある。太陽光パネルや電子廃棄物のリサイクル方法に関する研究も行われている。これにより、材料の供給源が確保され、採掘の必要がなくなるだろう。 | ||

学者たちは、緩和策のリスクと負の副作用に関する議論が、行き詰まりや、行動を起こす上での克服不可能な障壁があるという感覚につながる可能性があることを発見した。 | |||

== 費用と資金 == | |||

= | {{Main/ja|:en:Economics of climate change mitigation#Assessing costs and benefits|:en:Economic analysis of climate change}} | ||

{{Main|Economics of climate change mitigation#Assessing costs and benefits|Economic analysis of climate change}} | |||

気候変動の影響緩和費用は、いくつかの要因によって変動する。一つはベースラインであり、これは代替の緩和シナリオと比較される参照シナリオである。その他には、費用がどのようにモデル化されるか、および将来の政府政策に関する仮定がある。特定の地域における緩和の費用推定は、将来その地域に許容される排出量の量、ならびに介入のタイミングに依存する。 | |||

緩和費用は、排出量がどのように、そしていつ削減されるかによって異なる。早期の周到な計画的行動は、費用を最小限に抑えるだろう。世界的に見ると、温暖化を2℃未満に抑えることによる利益は費用を上回るとされており、[[:en:The Economist|エコノミスト]]によれば、それは手頃な費用である。 | |||

経済学者たちは、気候変動緩和の費用をGDPの1%から2%と推定している。これは多額ではあるが、政府が[[苦境にある化石燃料産業]]に提供している補助金よりははるかに少ない。[[:en:International Monetary Fund|国際通貨基金]]はこれを年間5兆ドル以上と推定している。 | |||

別の推定では、気候変動緩和と適応のための資金フローは年間8000億ドル以上になるだろうと述べている。これらの財政的要件は、2030年までに年間4兆ドルを超えると予測されている。 | |||

世界的に見て、温暖化を2℃に制限することは、経済的費用よりも高い経済的利益をもたらす可能性がある。緩和の経済的影響は、政策設計と[[:en:international cooperation|国際協力]]のレベルに応じて、地域や家計間で大きく異なる。世界的な協力の遅れは、地域全体、特に現在比較的炭素集約度が高い地域において、政策コストを増加る。統一的な炭素価値を持つ経路は、より炭素集約的な地域、化石燃料輸出国、および貧しい地域でより高い緩和費用を示す。GDPや金銭的用語で表現された集計的な定量化は、貧しい国の家計への経済的影響を過小評価している。福利と幸福に対する実際の影響は、比較的に大きい。 | |||

[[:en:Cost–benefit analysis|費用便益分析]]は、気候変動緩和全体を分析するには不適切かもしれない。しかし、1.5℃目標と2℃目標の違いを分析するには依然として有用である。排出量を削減するコストを推定する方法の一つは、潜在的な技術的および生産の変化の可能性のあるコストを考慮することである。政策立案者は、様々な方法の[[:en:marginal abatement costs|限界削減費用]]を比較して、時間の経過に伴う可能な削減のコストと量を評価できる。様々な措置の限界削減費用は、国、セクター、および時間によって異なる。 | |||

[[Cost–benefit analysis]] | |||

輸入のみに対する[[:en:Eco-tariff|エコ関税]]は、世界的な輸出の[[:en:Competition (economics)|競争力]]の低下と[[:en:deindustrialisation|脱工業化]]に貢献する。 | |||

[[Eco-tariff]] | |||

=== 気候変動の影響によるコストの回避 === | |||

== | {{See also/ja|:en:Economic impacts of climate change}} | ||

{{See also|Economic impacts of climate change}} | |||

[[:en:effects of climate change|気候変動の影響]]を限定することで、気候変動によるコストの一部を回避することが可能である。[[:en:Stern Review|スターン・レビュー]]によると、行動しない場合、現在そして未来永劫、毎年世界のGDPの少なくとも5%に相当する損失を被る可能性がある。より広範なリスクと影響を含めると、これはGDPの20%以上になることもある。しかし、気候変動を緩和するコストは、GDPの約2%に過ぎない。また、温室効果ガス排出量の大幅な削減を遅らせることは、財政的な観点からも得策ではないかもしれない。 | |||

緩和策は、しばしばコストと温室効果ガス削減の可能性という観点から評価される。しかし、これは人間の幸福に対する直接的な影響を考慮していない。 | |||

=== 排出量削減コストの配分 === | |||

=== | 温暖化を2℃以下に抑えるために必要な速度と規模での緩和は、深い経済的・構造的変化を伴う。これらは、地域、所得階級、部門間で複数の種類の分配上の懸念を引き起こす。 | ||

排出量削減の責任をどのように配分するかについては、様々な提案がなされてきた。これらには、[[:en:egalitarianism|平等主義]]、最低限の消費水準に基づく[[:en:basic needs|基本的ニーズ]]、比例原則、そして[[:en:Polluter pays principle|汚染者負担原則]]が含まれる。具体的な提案の一つに「一人当たり均等配分」がある。このアプローチには2つのカテゴリーがある。最初のカテゴリーでは、排出量が国家人口に応じて配分される。2番目のカテゴリーでは、排出量が歴史的または累積的な排出量を考慮しようとする方法で配分される。 | |||

===融資=== | |||

{{main/ja|:en:Climate finance|Economics of climate change mitigation#Finance}} | |||

{{main|Climate finance|Economics of climate change mitigation#Finance}} | |||

経済発展と炭素排出量削減を両立させるために、開発途上国は特に財政的・技術的な支援を必要としている。 | |||

IPCCは、このような支援を加速させることで、気候変動に対する財政的・経済的脆弱性における不平等を解決できるとも指摘しています。この目標を達成する一つの方法として、京都議定書の[[:en:Clean Development Mechanism|クリーン開発メカニズム]](CDM)が挙げられる。 | |||

< | <span id="Policies"></span> | ||

== Policies == | == 政策{{Anchor|Policies}} == | ||

=== 国家政策 === | |||

=== | [[File:Total CO2 emissions by country in 2017 vs per capita emissions (top 40 countries).svg|thumb|中国は世界のCO<sub>2</sub>排出量で首位、米国が2位だが、一人当たりでは米国が中国をかなり上回っている(2017年データ)。]] | ||

[[File:Total CO2 emissions by country in 2017 vs per capita emissions (top 40 countries).svg|thumb| | 気候変動緩和策は、個人や国家の社会経済的地位に大きく複雑な影響を与えうる。これは正負両方の場合がある。政策を適切に設計し、包摂的にすることが重要である。そうしないと、気候変動緩和策が貧困世帯に高い財政的負担を課す可能性がある。 | ||

< | 1998年から2022年の間に実施された1,500件の気候政策介入について評価が行われた。この介入は41カ国、6大陸にわたり、2019年時点で世界の総排出量の81%を占めていた。評価の結果、大幅な排出量削減をもたらした63件の成功した介入が判明した。これらの介入によって回避された総CO<sub>2</sub>排出量は0.6億トンから1.8億メトリックトンであった。この研究は4.5%以上の排出量削減をもたらした介入に焦点を当てたが、研究者たちはパリ協定が要求する削減量を満たすには年間230億メトリックトンが必要であると指摘した。一般的に、炭素価格は[[:en:Developed country|先進国]]で最も効果的であることが判明し、規制は[[:en:Developing country|開発途上国]]で最も効果的であることが判明した。補完的な政策ミックスは相乗効果の恩恵を受け、孤立した政策の実施よりも効果的な介入であることがほとんどであった。 | ||

OECDは、国家レベルでの実施に適した48種類の異なる気候緩和政策を認識している。これらは大きく3つのタイプに分類できる:「市場ベース」の手段、「非市場ベース」の手段、および「その他の」政策である。 | |||

* 「'''その他の'''」政策には、「独立した気候諮問機関の設立」が含まれる。 | |||

* ''' | * 「'''非市場ベース'''」の政策には、「規制基準の導入または強化」が含まれる。これらは技術または性能基準を定めるものである。これらは情報の非対称性という市場の失敗に対処するのに効果的である。 | ||

* ''' | *「'''市場ベース'''」の政策の中で、炭素価格が最も効果的であることが判明しており(少なくとも先進国では)、後述の専用の節がある。気候変動緩和のための追加の「市場ベース」の政策手段には以下が含まれる。 | ||

* | 「排出税」これらはしばしば、国内の排出者に対し、大気中に排出するCO<sub>2</sub>1トンあたり固定料金または税金を支払うことを要求する。化石燃料採掘からのメタン排出も時折課税される。しかし、農業からのメタンと亜酸化窒素は通常課税されない。 | ||

<br />「有害な補助金の撤廃」多くの国が排出に影響を与える活動に補助金を提供している。例えば、多くの国で多額の化石燃料補助金が存在する。[[:en:Fossil fuel phase-out#Phase-out of fossil fuel subsidies|化石燃料補助金の段階的廃止]]は、気候危機に対処するために極めて重要である。しかし、抗議運動や貧困層をさらに貧しくすることを避けるために、慎重に行われる必要がある。 | |||

<br /> | <br />「有益な補助金の創設」補助金や財政的インセンティブの創設。一例は、潮流発電など、まだ商業的に実行可能ではないクリーンな発電を支援するためのエネルギー補助金である。 | ||

<br /> | <br />「[[:en:Tradable permits|排出権取引制度]]」[[:en:carbon emission trading|排出権取引制度]]は排出量を制限できる。 | ||

<br /> | |||

==== カーボンプライシング ==== | |||

==== | {{Main/ja|:en:Carbon price}} | ||

{{Main|Carbon price}} | |||

[[File:ETS-allowance-prices.svg|thumb|upright=1.35|炭素排出権取引 – 2008年からの排出枠価格]] | |||

[[File:ETS-allowance-prices.svg|thumb|upright=1.35| | 温室効果ガス排出に追加費用を課すことで、化石燃料の競争力を低下させ、低炭素エネルギー源への投資を加速させることができる。固定された[[炭素税]]を課す、または動的な[[:en:carbon emission trading|炭素排出権取引]](ETS)システムに参加する国が増加している。2021年には、世界の温室効果ガス排出量の21%以上が炭素価格によってカバーされた。これは、[[:en:Chinese national carbon trading scheme|中国全国炭素排出権取引スキーム]]の導入により、以前よりも大幅な増加である。 | ||

< | 排出量取引制度は、特定の削減目標に対して排出枠を制限する可能性を提供する。しかし、排出枠の過剰供給により、ほとんどのETSは低価格水準の10ドル前後にとどまり、影響は小さい。これには、2021年に7ドル/トンCO<sub>2</sub>で始まった中国のETSも含まれる。唯一の例外は[[:en:European Union Emission Trading Scheme|欧州連合排出量取引制度]]であり、ここでは価格が2018年に上昇し始め、2022年には約80ユーロ/トンCO<sub>2</sub>に達した。これにより、[[:en:emission intensity|排出原単位]]にもよるが、石炭火力発電で約0.04ユーロ/KWh、ガス火力発電で約0.02ユーロ/KWhの追加費用が発生する。エネルギー要件が高く排出量の多い産業は、しばしば非常に低いエネルギー税しか支払わないか、全く支払わないことが多い。 | ||

これは国家スキームの一部であることが多いが、[[:en:carbon offsets and credits|炭素オフセットとクレジット]]は、国際市場のような自主的な市場の一部となることもできる。特に、アラブ首長国連邦の[[:en:Blue Carbon (company)|Blueカーボン]]社は、炭素クレジットと引き換えに、イギリスに匹敵する面積の土地を保全するために所有権を購入した。 | |||

=== 国際協定 === | |||

{{Main/ja|:en:Politics of climate change}} | |||

{{Main|Politics of climate change}} | |||

{{See also/ja|:en:Climate change#Policies and politics|:en:Climate change mitigation framework}} | |||

{{See also|Climate change#Policies and politics|Climate change mitigation framework}} | |||

[[:en:International cooperation|国際協力]]は、気候変動対策にとって「極めて重要な推進力」であると考えられている。ほとんど全ての国が国際連合[[:en:United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change|気候変動枠組条約]](UNFCCC)の締約国である。UNFCCCの究極の目的は、温室効果ガスの大気中濃度を、気候システムに対する危険な人為的干渉を防ぐ水準で安定させることである。 | |||

[[International cooperation]] | |||

[[:en:Montreal Protocol|モントリオール議定書]]は、その本来の目的ではありませんでしたが、気候変動緩和の取り組みに恩恵をもたらしました。この国際条約は、[[:en:Chlorofluorocarbon|CFC]]などの[[:en:ozone-depleting substance|オゾン層破壊物質]]の排出量を削減することに成功した。 | |||

==== パリ協定 ==== | |||

= | [[File:ParisAgreement.svg|thumb|[[Paris Agreement/ja#Parties and signatories|パリ協定の署名国(黄)と締約国(青)]]]] | ||

[[File:ParisAgreement.svg|thumb|[[Paris Agreement#Parties and signatories| | {{excerpt|Paris Agreement/ja|paragraphs=2|file=no}} | ||

{{excerpt|Paris Agreement|paragraphs= | |||

==歴史{{Anchor|History}}== | |||

== History == | {{See also/ja|:en:Climate change mitigation framework|:en:History of climate change policy and politics|:en:Kyoto Protocol#Chronology|Paris Agreement/ja#Development}} | ||

{{See also|Climate change mitigation framework|History of climate change policy and politics|Kyoto Protocol#Chronology|Paris Agreement#Development}} | 歴史的に、気候変動に対処する努力は多国間レベルで行われてきた。これらは、国際連合[[:en:United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change|気候変動枠組条約]](UNFCCC)の下で、国連におけるコンセンサス決定に達する試みを含んでいる。これは、世界的な公共問題に対してできるだけ多くの国際政府を行動に参加させるという、歴史的に支配的なアプローチである。1987年の[[:en:Montreal Protocol|モントリオール議定書]]は、このアプローチが機能しうるという先例である。しかし、一部の批評家は、UNFCCCのコンセンサスアプローチのみを利用するトップダウン型枠組みは非効果的だと述べている。彼らはボトムアップ型ガバナンスの対案を提示している。同時に、これはUNFCCCへの重点を軽減するだろう。 | ||

1997年に採択されたUNFCCCの[[:en:Kyoto Protocol|京都議定書]]は、「付属書I」国に対する法的拘束力のある排出削減コミットメントを定めた。議定書は、付属書I国が排出削減コミットメントを達成するために使用できる3つの国際政策手段(「[[:en:Flexibility mechanisms|柔軟性メカニズム]]」)を定義した。バシュマコフによると、これらの手段の使用は、付属書I国が排出削減コミットメントを達成するためのコストを大幅に削減できる可能性がある。 | |||

2015年に締結された[[Paris Agreement/ja|パリ協定]]は、2020年に期限切れとなった[[Kyoto Protocol|京都議定書]]の後継である。[[:en:List of Kyoto Protocol signatories|京都議定書を批准した国々]]は、二酸化炭素および他の5つの[[温室効果ガス]]の排出量を削減するか、これらのガスの排出量を維持または増加させる場合は[[:en:carbon emissions trading|炭素排出権取引]]を行うことをコミットした。 | |||

2015年、UNFCCCの「構造化専門家対話」は、「一部の地域や脆弱な生態系では、1.5℃を超える温暖化でも高いリスクが予測される」という結論に達した。最も貧しい国々や太平洋の島嶼国家の強い外交的声と相まって、この専門家の知見は、2015年の[[:en:2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference|パリ気候会議]]の決定を推進する原動力となり、既存の2℃目標に加えてこの1.5℃の長期目標を掲げることになった。 | |||

==障壁{{Anchor|Barriers}}== | |||

== Barriers == | {{See also/ja|:en:Economic analysis of climate change#Economic barriers to addressing climate change mitigation|:en:Climate change denial|:en:Public opinion on climate change|:en:Sustainability#Barriers}} | ||

{{See also|Economic analysis of climate change#Economic barriers to addressing climate change mitigation|Climate change denial|Public opinion on climate change|Sustainability#Barriers}} | [[File:A typology of climate delay discourses.png|thumb|気候変動緩和策を遅らせることを目的とした言説の類型論]] | ||

[[File:A typology of climate delay discourses.png|thumb| | [[File:Distribution of committed CO2 emissions from developed fossil fuel reserves.jpg|thumb|upright=1.35|開発済み化石燃料埋蔵量からの確定済み{{CO2}}排出量の分布]] | ||

[[File:Distribution of committed CO2 emissions from developed fossil fuel reserves.jpg|thumb|upright=1.35| | |||

気候変動緩和策を達成するには、個人、制度、市場の障壁が存在する。これらは、さまざまな緩和策、地域、社会によって異なる。 | |||

[[:en:Carbon accounting|二酸化炭素除去の会計]]に関する困難は、経済的障壁となりうる。これはBECCS([[:en:bioenergy with carbon capture and storage|バイオエネルギーと炭素回収・貯留]])に当てはまる。企業がとる戦略も障壁となりうるが、脱炭素化を加速させることもできる。 | |||

社会を脱炭素化するためには、国家が主導的な役割を果たす必要がある。これは、大規模な調整努力が必要だからである。この強力な政府の役割は、社会凝集性、政治的安定性、信頼がある場合にのみうまく機能する。 | |||

陸上ベースの緩和策にとって、金融は大きな障壁である。その他の障壁としては、文化的価値観、ガバナンス、説明責任、制度的能力が挙げられる。 | |||

発展途上国は、緩和に関してさらなる障壁に直面している。 | |||

* 2020年代初頭に資本コストが増加した。利用可能な資本と資金の不足は、発展途上国では一般的である。規制基準の欠如と相まって、この障壁は非効率な設備の拡散を助長している。 | |||

* | * これらの国の多くには、財政的および[[:en:Capacity building|能力]]の障壁も存在する。 | ||

* | |||

ある研究では、気候関連研究への総資金のわずか0.12%しか気候変動緩和の社会科学に向けられていないと推定されている。はるかに多くの資金が気候変動に関する自然科学研究に向けられている。また、気候変動の影響とその適応に関する研究にもかなりの金額が費やされている。 | |||

< | <span id="Society_and_culture"></span> | ||

== Society and culture | ==社会と文化== | ||

{{Anchor|Society and culture}} | |||

===コミットメントを[[divestment|売却]]する=== | |||

[[File:Climate investment is stalling, but more firms plan to invest, with firms in low-carbon sectors taking the lead.jpg|thumb|upright=1.35|気候変動緩和策への投資を計画している企業が増加しており、特に低炭素セクターの企業が主導している。]] | |||

[[File:Climate investment is stalling, but more firms plan to invest, with firms in low-carbon sectors taking the lead.jpg|thumb|upright=1.35| | 8兆米ドル相当の投資を持つ1000以上の組織が、[[:en:fossil fuel divestment|化石燃料からの投資撤退]]をコミットしている。社会的責任投資ファンドは、投資家が高い[[:en:environmental, social and corporate governance|環境・社会・企業統治]](ESG)基準を満たすファンドに投資することを可能にする。 | ||

=== COVID-19パンデミックの影響 === | |||

=== | {{Main/ja|:en:Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the environment#Climate change}} | ||

{{Main|Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the environment#Climate change}} | |||

[[:en:COVID-19 pandemic|COVID-19パンデミック]]は、一部の政府が気候変動対策から、少なくとも一時的に焦点を移す原因となった。この環境政策への障害は、グリーンエネルギー技術への投資減速の一因となった可能性がある。COVID-19による経済活動の停滞も、この影響をさらに大きくした。 | |||

2020年には、世界の二酸化炭素排出量が6.4%、つまり23億トン減少した。しかし、パンデミック中に多くの国が制限を解除し始めると、温室効果ガス排出量はその後反発した。パンデミック政策の直接的な影響は、気候変動に対する長期的な影響としてはごくわずかであった。 | |||

==国別の事例{{Anchor|Examples by country}}== | |||

== Examples by country == | {{Imageright| | ||

{{multiple image | {{multiple image | ||

| total_width | | total_width = 450 | ||

| image1 | | image1 = 20210626 Variwide chart of greenhouse gas emissions per capita by country.svg | ||

| caption1 | | caption1 = 排出量の多い国々における一人当たりの温室効果ガス排出量。中国は年間総二酸化炭素排出量が最も多いものの、米国やその他の少数の高排出国は、一人当たり排出量で中国を上回っている。 | ||

| image2 | | image2 = 2021 Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions per person versus GDP per person - scatter plot.svg | ||

| caption2 | | caption2 = 裕福な[[:en:Developed country|(先進国)]]は、貧しい[[:en:Developing country|(発展途上国)]]よりも一人当たりのCO2排出量が多い。排出量は一人当たりの[[:en:Gross domestic product|GDP]]にほぼ比例するが、一人当たりの平均GDPが約1万ドルを超えると増加率は減少する。 | ||

}} | }}}} | ||

=== 米国 === | === 米国 === | ||

Latest revision as of 09:50, 19 July 2025

気候変動緩和策(または脱炭素化)は、温室効果ガスを大気中で制限し、気候変動の原因を排除するための行動である。気候変動緩和策には、エネルギーを節約することや、化石燃料を持続可能なエネルギーに置き換えることが含まれる。二次的な緩和戦略には、土地利用の変化や、大気からの二酸化炭素(CO2)除去がある。現在の気候変動緩和政策は不十分であり、2100年までに約2.7℃の地球温暖化をもたらすだろう。これは、2015年のパリ協定が目標とする2℃未満への地球温暖化抑制を大幅に上回る。

太陽エネルギーと風力発電は、他の再生可能エネルギーの選択肢と比較して、最も低いコストで化石燃料を代替できる。日照と風の利用可能性は変動するため、電力網のアップグレードが必要となる場合がある。例えば、様々な電源をまとめるための長距離送電の利用が挙げられる。エネルギー貯蔵も電力出力を均等化するために使用でき、電力生成が低い場合にはデマンドマネジメントによって電力使用を制限できる。クリーンに生成された電力は、通常、輸送機関の動力源、建物の暖房、産業プロセスの稼働において化石燃料を代替できる。航空やセメント生産など、特定のプロセスは脱炭素化がより困難である。このような状況では、炭素回収・貯留(CCS)が正味排出量を削減する選択肢となりうるが、CCS技術を備えた化石燃料発電所は、現在のところ高コストの気候変動緩和策である。

農業や森林破壊といった人間の土地利用の変化は、気候変動の約4分の1を引き起こしている。これらの変化は、植物によって吸収されるCO

2の量や、有機物が腐敗または燃焼して CO

2を放出する量に影響を与える。これらの変化は速い炭素循環の一部である一方、化石燃料は遅い炭素循環の一部として地中に埋蔵されていたCO2を放出する。メタンは、腐敗する有機物や家畜、化石燃料の採掘によって生成される短命の温室効果ガスである。土地利用の変化は、降水パターンや地表の反射率にも影響を与える可能性がある。農業からの排出量を削減するには、食品ロスと廃棄物を減らすこと、より植物ベースの食事(低炭素食とも呼ばれる)に切り替えること、そして農業プロセスを改善することが可能である。

様々な政策が気候変動緩和を促進しうる。炭素価格設定システムが導入されており、それはCO2排出量を課税するか、あるいは総排出量に上限を設け、排出枠を取引するかのいずれかである。化石燃料補助金は、クリーンエネルギー補助金を有利にする形で廃止でき、エネルギー効率対策の導入や電力源への転換に対するインセンティブが提供される。もう一つの問題は、新しいクリーンエネルギー源の建設や送電網の変更を行う際に生じる環境上の異論を克服することである。温室効果ガス排出量の削減または大気からの温室効果ガスの除去による気候変動の抑制は、日射管理(または太陽地球工学)のような気候技術によって補完されうる。補完的な気候変動対策には、気候変動活動が含まれ、政治的および文化的側面に焦点が当てられている。

定義と範囲

| Part of a series on |

| Climate change mitigation |

|---|

気候変動緩和は、生態系を維持して人間文明を保全することを目指している。これには温室効果ガス排出量の大幅な削減が必要である。気候変動に関する政府間パネル(IPCC)は、(気候変動の)「緩和」を「排出を削減するか、温室効果ガスの吸収源を強化するための人間による介入」と定義している。

様々な気候変動緩和策を並行して進めることが可能である。これは、地球温暖化を1.5度または2度に制限するための単一の道筋が存在しないためである。対策には以下の4つの種類がある。

- 持続可能なエネルギーおよび持続可能な輸送

- エネルギー保全(効率的なエネルギー利用を含む)

- 持続可能な農業およびグリーン産業政策

- 炭素吸収源の強化と二酸化炭素除去(CDR)(炭素隔離を含む)

IPCCは、二酸化炭素除去を「大気中のCO

2を人為的に除去し、地質学的、陸域、または海洋の貯留層、あるいは製品中に永続的に貯蔵する人間活動。既存および潜在的な生物学的または地球化学的CO

2吸収源の人為的強化、および直接空気炭素回収・貯蔵(DACCS)を含むが、人間の活動によって直接引き起こされない自然なCO

2吸収は含まない」と定義している。

排出の傾向と誓約

GHG排出量 2020年 ガスタイプ別

土地利用変化を含まず

100年GWPを使用

合計: 49.8 GtCO

2e

2 主に化石燃料による (72%)

2O 亜酸化窒素 (6%)

CO

2排出量 燃料種別

人間活動による温室効果ガス排出は温室効果を強め、これが気候変動の一因となっている。そのほとんどは、化石燃料(石炭、石油、天然ガス)の燃焼による二酸化炭素だ。人間が引き起こした排出により、大気中の二酸化炭素は産業革命以前のレベルから約50%増加した。2010年代の排出量は年間平均560億トン(Gt)と過去最高を記録した。2016年には、電力、熱、輸送のためのエネルギーが温室効果ガス排出量の73.2%を占めた。直接的な産業プロセスが5.2%、廃棄物が3.2%、農業、林業、土地利用が18.4%を占めている。

発電と輸送は主要な排出源である。最大の単一排出源は石炭火力発電所で、温室効果ガス排出量の20%を占める。森林破壊やその他の土地利用の変化も二酸化炭素やメタンを排出する。人為的なメタン排出の最大の発生源は農業、そしてガス抜きや化石燃料産業からの漏出である。農業における最大のメタン発生源は家畜である。農地の土壌は、一部は肥料が原因で亜酸化窒素を排出する。現在、冷媒からのフッ素化ガスの問題には政治的な解決策がある。これは、多くの国がキガリ改正を批准したためである。

二酸化炭素(CO2)は、排出される温室効果ガスの中で最も優勢である。メタン(CH4)排出量は、短期的にはほぼ同じ影響力を持つ。亜酸化窒素(N2O)とフッ素化ガス(F-ガス)は軽微な役割を果たす。家畜とその排泄物は、全温室効果ガス排出量の5.8%を占める。しかし、この割合は、それぞれのガスの地球温暖化係数を計算するために使用される時間枠によって異なる。

温室効果ガス(GHG)排出量は、CO2換算量で測定される。科学者は、それぞれの地球温暖化係数(GWP)からCO2換算量を決定する。これは大気中での寿命によって決まる。メタン、亜酸化窒素、その他の温室効果ガスの量を二酸化炭素換算量に変換する温室効果ガス会計手法が広く用いられている。推定値は、海洋や陸上吸収源がこれらのガスを吸収する能力に大きく依存する。短寿命気候汚染物質(SLCP)は、数日から15年の期間、大気中に残留する。二酸化炭素は何千年もの間、大気中に留まることがある。短寿命気候汚染物質には、メタン、ハイドロフルオロカーボン(HFC)、対流圏オゾン、ブラックカーボンが含まれる。

科学者たちは、人工衛星を用いて温室効果ガス排出量と森林破壊の位置特定と測定を行うことが増えています。以前は、科学者たちは主に温室効果ガス排出量の推定値や政府の自己申告データに頼っていましたが、現在は衛星による直接的な観測が進んでいる。

必要な排出削減量

UNEPによる年次「排出量ギャップ報告書」は、2022年に排出量をほぼ半減させる必要があると述べた。地球温暖化を1.5℃に制限する軌道に乗るためには、世界の年間GHG排出量を、現在実施されている政策の下での排出予測と比較して、わずか8年間で45%削減しなければならない。そして、残された限られた大気中の炭素予算を使い果たさないために、2030年以降も急速に減少し続けなければならない。」同報告書は、世界は漸進的な変化ではなく、広範な経済全体の変革に焦点を当てるべきだとコメントした。

2022年、気候変動に関する政府間パネル(IPCC)は第6次評価報告書を公表した。同報告書は、地球温暖化を1.5℃(2.7°F)に抑える良い機会を得るためには、温室効果ガス排出量が遅くとも2025年までにピークを迎え、2030年までに43%減少する必要があると警告している。あるいは、国際連合事務総長のアントニオ・グテーレスの言葉を借りれば、「主要な排出国は、今年から排出量を劇的に削減しなければならない」。

有力な気候科学者らによる2023年の統合報告書は、政策に重大な影響を与える気候科学における10の重要な分野を強調した。これらには、1.5℃の温暖化限界を一時的に超えることのほぼ不可避性、化石燃料の迅速かつ管理された段階的廃止の緊急の必要性、二酸化炭素除去技術の規模拡大における課題、自然の炭素吸収源の将来の寄与に関する不確実性、および生物多様性損失と気候変動の相互に関連する危機が含まれる。これらの洞察は、気候変動の多面的な課題に対処するための、即時かつ包括的な緩和戦略の必要性を強調している。

誓約

クライメート・アクション・トラッカーは、2021年11月9日時点の状況を次のように記述した。現在の政策では、今世紀末までに世界の気温は2.7℃上昇し、各国が採択した政策では2.9℃上昇するだろう。各国が2030年の誓約のみを実施した場合、気温は2.4℃上昇する。長期目標も達成された場合、上昇は2.1℃となるだろう。発表されたすべての目標が完全に達成された場合、世界の気温上昇は1.9℃でピークに達し、2100年までに1.8℃に低下するだろう。

2020年までに設定されたほとんどの目標について、決定的または詳細な評価は行われていない。しかし、世界はその年に設定された国際目標のほとんど、あるいは全てを達成できなかったようである。

グラスゴーで開催された2021年国連気候変動会議で一つの進展があった。「クライメート・アクション・トラッカー」を運営する研究者グループは、温室効果ガス排出量の85%を占める国々を調査した。その結果、EU、英国、チリ、コスタリカの4つの国または政治的実体のみが、2030年の緩和目標を達成するための具体的な手順を記述した詳細な公式政策計画を発表していることが判明した。これらの4つの政治体は、世界の温室効果ガス排出量の6%を担っている。

2021年、米国とEUは、2030年までにメタン排出量を30%削減するグローバル・メタン・プレッジを立ち上げた。英国、アルゼンチン、インドネシア、イタリア、メキシコがこのイニシアチブに参加した。ガーナとイラクは参加への関心を示した。ホワイトハウスの会議要約によると、これらの国々は世界のメタン排出量上位15カ国のうち6カ国を占めている。

低炭素エネルギー

エネルギーシステムには、エネルギーの供給と利用が含まれる。これはCO

2の主要な排出源である。地球温暖化を2℃を十分に下回るように制限するためには、エネルギー部門からの二酸化炭素およびその他の温室効果ガス排出量の迅速かつ大幅な削減が必要である。IPCCの提言には、化石燃料消費の削減、低炭素およびゼロ炭素エネルギー源からの生産増加、そして電力と代替エネルギーキャリアの使用増加が含まれる。

ほぼ全てのシナリオと戦略は、再生可能エネルギーの利用を大幅に増加させるとともに、エネルギー効率対策の強化を伴っている。地球温暖化を2℃未満に抑えるためには、再生可能エネルギーの導入を2015年の年間成長率0.25%から1.5%へと6倍に加速する必要があるだろう。

再生可能エネルギーの競争力は、その迅速な導入の鍵となります。2020年には、多くの地域で陸上風力発電と太陽光発電が、新規の大規模電力生産において最も安価な電源となった。再生可能エネルギーは貯蔵コストが高い場合があるが、非再生可能エネルギーは環境浄化コストが高くなる可能性がある。炭素価格は、再生可能エネルギーの競争力を高めることができる。

太陽エネルギーと風力エネルギー

風力と太陽光は、競争力のある生産コストで大量の低炭素エネルギーを供給できる。IPCCは、これら2つの緩和策が2030年までに低コストで排出量を削減する最大の可能性を秘めていると推定しる。

太陽光発電(PV)は、世界の多くの地域で最も安価な発電方法となっている。太陽光発電の成長はほぼ指数関数的であり、1990年代以降、約3年ごとに倍増している。異なる技術として集光型太陽熱発電(CSP)がある。これは、鏡やレンズを用いて広い範囲の太陽光を受光器に集中させる。CSPでは、エネルギーを数時間貯蔵できるため、夕方に供給が可能となる。太陽熱温水器は2010年から2019年の間に倍増した。

高緯度の北半球および南半球の地域は、風力発電の最大の可能性を秘めている。洋上風力発電所はより高価だが、洋上設備は設備容量あたりの発電量が多く、変動が少ない。ほとんどの地域で、風力発電はPV出力が低い冬に高くなる。このため、風力と太陽光発電の組み合わせは、よりバランスの取れたシステムにつながる。

その他の再生可能エネルギー

その他の確立された再生可能エネルギー源には、水力発電、バイオエネルギー、地熱エネルギーがある。

- 水力発電は水力によって発電され、ブラジル、ノルウェー、中国などの国々で主導的な役割を果たしている。しかし、地理的な限界や環境問題も存在する。潮力発電は沿岸地域で利用できる。

- バイオエネルギーは、電力、熱、輸送のためのエネルギーを供給できる。バイオエネルギー、特にバイオガスは、ディスパッチャブル発電を提供できる。植物由来のバイオマスを燃焼させるとCO

2が放出されるが、植物は成長中に大気からCO

2を吸収する。燃料の生産、輸送、加工の技術は、その燃料のライフサイクル排出量に大きな影響を与える。例えば、航空業界は再生可能なバイオ燃料の使用を開始している。 - 地熱発電は、地熱エネルギーから発電される電力である。地熱発電は現在26カ国で利用されている。地熱暖房は70カ国で利用されている。

変動する再生可能エネルギーの統合

風力発電と太陽光発電の電力生産は、常に需要と一致するわけではない。風力や太陽光のような変動性再生可能エネルギー源から信頼性の高い電力を供給するためには、電力システムが柔軟でなければならない。ほとんどの電力網は、石炭火力発電所のような非間欠的なエネルギー源のために構築された。より大量の太陽光および風力エネルギーを系統に統合するには、エネルギーシステムの変更が必要である。これは、電力供給が需要と一致することを確実にするために必要である。

電力システムをより柔軟にするための様々な方法がある。多くの場所で、風力発電と太陽光発電は日ごとおよび季節ごとの規模で補完的である。太陽エネルギー生産が低い夜間や冬には、より多くの風が吹く。異なる地理的地域を長距離送電線で結ぶことも、変動性を減らすことを可能にする。エネルギー需要を時間的にシフトさせることも可能である。エネルギー需要管理とスマートグリッドの利用は、変動性エネルギー生産が最も高い時間帯に合わせることを可能にする。セクターカップリングはさらなる柔軟性を提供できる。これには、パワー・トゥ・ヒートシステムと電気自動車を介して、電力部門を熱およびモビリティ部門に結合させることが含まれる。

エネルギー貯蔵は、間欠性再生可能エネルギーの障壁を克服するのに役立つ。最も一般的に使用され、利用可能な貯蔵方法は揚水発電である。これには、大きな高低差と水へのアクセスが必要である。これらは通常、短期間の電力を貯蔵する。バッテリーはエネルギー密度が低い。このこととコストのために、エネルギー生産の季節間の変動を均衡させるために必要な大規模なエネルギー貯蔵には実用的ではない。一部の場所では、数ヶ月間の使用が可能な揚水式水力貯蔵が実施されている。

原子力

原子力は電力のために再生可能エネルギーを補完しうる。一方で、環境上および安全保障上のリスクがその利益を上回る可能性もある。これらの環境リスクの例としては、放射性水の近隣生態系への排出や、放射性ガスの日常的な放出が挙げられる。

新しい原子炉の建設には現在約10年かかり、これは風力発電や太陽光発電の導入拡大よりもはるかに長い。そして、この期間は信用リスクを生じさせる。しかし、中国では原子力がはるかに安価である可能性がある。中国は相当数の新しい発電所を建設している。2019年時点で、原子力の廃棄物処分の長期費用を計算から除外した場合、原子力発電所の寿命延長費用は他の発電技術と競争力がある。また、原子力事故に対する十分な財政保険も存在しない。

石炭を天然ガスに置き換える

石炭から天然ガスへの転換は、持続可能性の観点から利点がある。生産されるエネルギー単位あたりで比較すると、天然ガスのライフサイクル温室効果ガス排出量は風力や原子力の約40倍だが、石炭よりははるかに少ない。発電に利用する場合、天然ガスの燃焼による排出量は石炭の約半分であり、熱生産に利用する場合は石炭の約3分の2となる。また、天然ガスの燃焼は石炭よりも大気汚染物質の排出が少ない。しかし、天然ガス自体が強力な温室効果ガスであり、採掘や輸送中の漏出は、石炭からの転換による利点を帳消しにしてしまう可能性がある。メタン漏出を抑制する技術は広く利用可能だが、常に使用されているわけではない。

石炭から天然ガスへの転換は、短期的には排出量を削減するため、気候変動緩和に貢献する。しかし、長期的には正味ゼロ排出への道筋を提供するものではない。天然ガスインフラの開発は、炭素のロックインや座礁資産のリスクを伴う。これは、新たな化石燃料インフラが数十年にわたる炭素排出を約束するか、利益を上げる前に償却されなければならない状況を指す。需要削減

温室効果ガス排出を引き起こす製品やサービスへの需要を減らすことは、気候変動の緩和に役立つ。一つは、行動や文化の変化によって需要を減らすことである。例えば、食事を変えること、特に食肉消費を減らすという決定は、個人が気候変動と闘うための効果的な行動である。もう一つは、公共交通機関ネットワークの整備など、インフラを改善することによって需要を減らすことである。最後に、最終用途技術の変化によってエネルギー需要を減らすことができる。例えば、断熱性の良い家は、断熱性の悪い家よりも排出量が少ない。

製品やサービスへの需要を減らす緩和策は、人々が自身の炭素排出量を削減するための個人的な選択をするのに役立つ。これは交通手段や食品の選択において当てはまる。したがって、これらの緩和策には需要削減に焦点を当てた多くの社会側面があり、それゆえ「需要側」の「緩和行動」である。例えば、社会経済的地位が高い人々は、低い人々よりも多くの温室効果ガス排出量を引き起こすことが多い。もし彼らが排出量を削減し、グリーン政策を推進すれば、これらの人々は低炭素ライフスタイルのロールモデルになる可能性がある。しかし、消費者には意識や知覚されたリスクなど、多くの心理的変数が影響を与える。

政府の政策は、需要側の気候変動緩和策を支援することも、妨げることもあり得ます。例えば、公共政策は、循環経済の概念を推進することで気候変動緩和を支援できます。温室効果ガス排出量の削減は、シェアリングエコノミーとも関連している。

経済成長と排出量の相関関係については議論がある。経済成長が必ずしも排出量の増加を意味するわけではなくなってきているようだ。

2024年に『ネイチャー・クライメート・チェンジ』誌に掲載された論文は、気候変動緩和戦略に行動科学を統合することの重要性を強調している。 この論文では、温室効果ガス排出量削減に向けた個人および集団の行動を改善するための6つの主要な提言が示されている。これには、研究における障壁の克服、学際的な協力の促進、実践的な行動志向型ソリューションの推進などが含まれる。 これらの洞察は、気候変動への対処において、行動科学が技術的・政策的措置と並んで極めて重要な役割を果たすことを示唆している。

エネルギー保全と効率

2018年には、世界の一次エネルギー需要が161,000テラワット時(TWh)を超えた。これは、電力、輸送、暖房の全てを含み、その際の損失も考慮した数値である。 特に輸送と電力生産において、化石燃料の利用効率は50%未満と低い。発電所や車両のモーターからは大量の熱が無駄に排出されている。実際に消費されたエネルギー量は大幅に少なく、116,000 TWhにとどまっている。

エネルギー保全とは、エネルギー消費量を減らすために、エネルギーサービスの使用量を減らす努力である。一つの方法は、エネルギーをより効率的に利用することである。これは、同じサービスを生産するために、以前よりも少ないエネルギーを使用することを意味する。もう一つの方法は、使用するサービスの量を減らすことである。これの例としては、運転を減らすことなどが挙げられる。エネルギー保全は、持続可能なエネルギーのヒエラルキーの頂点に位置する。消費者が無駄や損失を減らすことで、エネルギーを保全できる。技術のアップグレード、および運用と保守の改善は、全体的な効率改善につながる。

エネルギー効率(または「エネルギー効率化」)とは、製品やサービスを提供するために必要なエネルギー量を削減するプロセスである。建物のエネルギー効率(「グリーンビルディング」)、工業プロセス、および輸送の改善は、2050年までに世界のエネルギー需要を3分の1削減できる可能性がある。これは、温室効果ガスの世界的排出量を削減するのに役立つだろう。例えば、建物を断熱することで、熱的快適性を達成および維持するために必要な暖房および冷房エネルギーの使用量を減らすことができる。エネルギー効率の改善は、一般により効率的な技術や生産プロセスを採用することによって達成される。もう一つの方法は、一般的に受け入れられている方法を用いてエネルギー損失を減らすことである。

ライフスタイルの変化

気候変動に関する個人の行動は、多くの分野における個人的な選択を含みうる。これらには、食事、旅行、家庭でのエネルギー使用、商品やサービスの消費、家族構成などが含まれる。自身の炭素排出量を削減したいと願う人々は、頻繁な飛行機利用やガソリン車の回避、主に植物ベースの食事を摂ること、子どもの数を減らすこと、衣類や電気製品を長く使うことなど、影響の大きい行動をとることができる。これらのアプローチは、高消費型のライフスタイルを持つ高所得国の国民にとってより現実的である。当然ながら、電気自動車のような選択肢が利用できないため、低所得層の人々がこれらの変化を起こすことはより困難である。気候変動の原因としては、人口増加よりも過剰消費の方がより大きな責任がある。高消費型のライフスタイルは環境への影響が大きく、最も裕福な10%の人々がライフスタイルに起因する総排出量の約半分を排出している。

食生活の変更

一部の科学者によると、食肉と乳製品を避けることが、個人が環境負荷を減らす最も大きな方法であるという。菜食主義の食事が広く採用されれば、食品関連の温室効果ガス排出量を2050年までに63%削減できる可能性がある。中国は2016年に新しい食事ガイドラインを導入し、肉の消費量を50%削減し、それによって2030年までに年間1ギガトン(Gt)の温室効果ガス排出量を削減することを目指している。全体として、食品は消費ベースの温室効果ガス排出量の中で最大の割合を占めている。それは世界のカーボンフットプリントの約20%を占めている。全人為起源の温室効果ガス排出量のほぼ15%は、家畜部門に起因するとされている。

植物性食生活への移行は、気候変動の緩和に大きく貢献する。 特に、食肉消費を減らすことは、メタン排出量の削減に役立つ。もし高所得国が植物性食生活に切り替えた場合、畜産に利用されている広大な土地を自然の状態に戻すことが可能になる。これにより、今世紀末までに1000億トンのCO

2を隔離できる可能性がある。

包括的な分析によると、植物性食生活は排出量、水質汚染、土地利用を大幅に(75%も)削減する一方で、野生生物の破壊と水の使用量も減らすことが明らかになっている。

家族の規模

人口増加は、ほとんどの地域、特にアフリカにおいて温室効果ガス排出量の増加をもたらしている。しかし、経済成長は人口増加よりも大きな影響を与える。所得の増加、消費と食事パターンの変化、そして人口増加は、土地やその他の天然資源に圧力をかける。これにより、温室効果ガス排出量が増加し、炭素吸収源が減少する。一部の学者は、人口増加を抑制するための人道主義的な政策は、化石燃料の使用を終わらせ、持続可能な消費を奨励する政策とともに、広範な気候変動対策の一部であるべきだと主張している。女性の教育と性と生殖に関する健康、特に家族計画の進歩は、人口増加の削減に貢献できる。

炭素吸収源の保全と強化

2排出量の約58%は、植物の成長、土壌吸収、海洋吸収を含む炭素吸収源によって吸収されている。

重要な緩和策の一つは、「炭素吸収源の保全と強化」である。これは、地球の自然な炭素吸収源を管理し、大気からCO2を除去し、それを永続的に貯蔵する能力を維持または増加させることを指す。科学者たちはこのプロセスを炭素隔離とも呼ぶ。気候変動緩和の文脈において、IPCCは「吸収源(シンク)」を「大気から温室効果ガス、エアロゾル、または温室効果ガスの前駆体を除去するあらゆるプロセス、活動、メカニズム」と定義している。世界的に、最も重要な2つの炭素吸収源は植生と海洋である。

生態系の炭素隔離能力を高めるためには、農業と林業において変化が必要である。例としては、森林伐採を防ぎ、再植林によって自然生態系を復元することなどが挙げられる。地球温暖化を1.5℃に制限するシナリオは通常、21世紀にわたる二酸化炭素除去方法の大規模な使用を予測している。これらの技術への過度な依存とその環境影響について懸念がある。しかし、生態系の復元と土地利用転換の削減は、2030年までに最も排出量を削減できる緩和ツールの一つである。

陸上ベースの緩和策は、2022年のIPCCの緩和に関する報告書で「AFOLU緩和策」と呼ばれている。この略語は「農業、林業、その他の土地利用」を意味する。同報告書は、森林と生態系に関する関連活動からの経済的緩和可能性を次のように説明している。「森林およびその他の生態系(沿岸湿地、泥炭地、サバンナ、草原)の保全、管理の改善、および復元」。熱帯地域における森林伐採の削減には高い緩和可能性が見られる。これらの活動の経済的潜在力は、年間4.2〜7.4ギガトン(GtCO2-eq)と推定されている。

森林

保全

2007年に発表されたスターン・レビューは、森林破壊を抑制することが温室効果ガス排出量を削減するための非常に費用対効果の高い方法であると述べた。森林破壊の約95%は熱帯地域で発生しており、農業のための土地開墾が主な原因の一つである。一つの森林保全戦略は、土地に対する権利を公共所有から先住民に移転することである。土地の譲許はしばしば強力な採掘会社に与えられる。人間を排除し、さらには立ち退かせる要塞型保全と呼ばれる保全戦略は、しばしば土地のさらなる搾取につながる。これは、原住民が生き残るために採掘会社で働くようになるためである。

プロフォレステーションは、森林がその生態学的潜在能力を最大限に発揮できるよう促進することである。放棄された農地に再成長した二次林は、元の原生林よりも生物多様性が低いことが判明しており、これは緩和戦略となる。原生林はこれらの新しい森林よりも60%多くの炭素を貯蔵する。戦略には、リワイルディングや野生生物回廊の設置が含まれる。

植林、再植林および砂漠化の防止

植林とは、以前に樹木がなかった場所に木を植えることである。最大4000万ヘクタール(Mha)(6300 x 6300 km)をカバーする新規植林のシナリオは、2100年までに900ギガトン以上の炭素(2300ギガトンCO

2)の累積炭素貯蔵を示唆している。しかし、これらの植林は、その規模があまりに大きいため、ほとんどの自然生態系を排除したり、食料生産を減少させたりすることになるため、積極的な排出削減の実行可能な代替策ではない。一兆本の木キャンペーンはその一例である。しかし、生物多様性の保全も重要であり、例えば、すべての草地が森林への転換に適しているわけではない。草地は、炭素吸収源から炭素排出源にさえ変わりうる。

再植林とは、既存の荒廃した森林や最近まで森林であった場所に再び木を植えることである。再植林は、年間少なくとも1ギガトンCO2を削減でき、その推定費用は1トンCO2あたり5〜15ドルである。世界中の劣化した森林すべてを復元すれば、約205ギガトン炭素(750ギガトンCO2)を吸収できる可能性がある。集約農業と都市化の進展に伴い、放棄された農地の量が増加している。一部の推定では、伐採された原生林1エーカーあたり、50エーカー以上の新しい二次林が成長している。一部の国では、放棄された農地での再成長を促進することで、数年分の排出量を相殺できる可能性がある。

新しい木を植えることは費用がかかり、リスクの高い投資となることがある。例えば、サヘル地域で植えられた木の約80%は2年以内に枯れてしまう。再植林は、植林よりも高い炭素貯蔵の可能性を秘めている。長年森林伐採されてきた地域でさえ、生きた根や切り株の「地下の森」が残っている。在来種の自然な発芽を助けることは、新しい木を植えるよりも安価であり、生存率も高い。これには、成長を促進するための剪定や萌芽更新が含まれる。これはまた、薪炭材も提供し、そうでなければ森林破壊の主要な原因となる。このような農家主導型自然再生と呼ばれる慣行は何世紀も前から行われているが、実施における最大の障害は、樹木の所有権が国家にあることである。国家はしばしば材木権を企業に売却するため、地元住民は苗木を負債と見なし、引き抜いてしまう。マリやニジェールのような国での地元住民への法的援助や財産法の変更は、大きな変化をもたらした。科学者たちはこれらをアフリカにおける最大の肯定的な環境変革であると評している。法律が変わっていないナイジェリアのより不毛な土地との国境は、宇宙からでも識別可能である。

放牧地は世界の土地の半分以上を占め、陸上炭素の35%を隔離できる可能性がある。牧畜民とは、しばしば囲いのない放牧地で餌をとり移動する家畜の群れと共に移動する人々である。そのような土地は通常、他の種類の食料を栽培することができない。放牧地は大型の野生動物の群れと共進化してきたが、その多くは減少または絶滅しており、牧畜民の家畜の群れがそのような野生動物の群れに取って代わり、それによって生態系の維持に役立っている。しかし、広大な地域を広範囲にわたって移動する家畜の群れの動きは、政府によってますます制限されている。政府はしばしば、より収益性の高い用途のために土地に排他的な権利を与え、牧畜民をより囲まれた空間に制限している。これにより、土地の過放牧や砂漠化、そして遊牧民の紛争が生じている。

土壌

土壌炭素を増加させる多くの方法がある。これは複雑で、測定と計算が困難である。一つの利点は、例えばBECCSや植林よりも、これらの方法におけるトレードオフが少ないことである。

世界的に、健全な土壌を保護し、土壌炭素スポンジを回復させることで、年間76億トンの二酸化炭素を大気から除去できる可能性がある。これは米国の年間排出量よりも多い。樹木は地上で成長しながらCO2を捕捉し、地下により大量の炭素を分泌する。樹木は土壌炭素スポンジの形成に貢献する。地表で形成された炭素は、木材が燃焼すると直ちにCO2として放出される。枯れ木が手付かずのまま残された場合、分解が進むにつれて炭素の一部のみが大気中に戻る。

農業は土壌炭素を枯渇させ、土壌を生命を維持できない状態にする可能性がある。しかし、保全農業は土壌中の炭素を保護し、時間をかけて損傷を修復できる。被覆作物の農法は炭素農業の一形態である。土壌中の炭素隔離を高める方法には、不耕起栽培、残渣マルチング、輪作などがある。科学者たちは、土壌有機炭素を増加させるためのヨーロッパの土壌に対する最良の管理方法を記述している。これらは、耕作地から牧草地への転換、藁の投入、耕うんの削減、耕うんの削減と藁の投入の組み合わせ、休閑作物システム、被覆作物である。

もう一つの緩和策は、バイオ炭の生産と土壌への貯蔵である。これはバイオマスの熱分解後に残る固形物質である。バイオ炭の生産は、バイオマスからの炭素の半分を大気中に放出するかCCSで捕捉し、残りの半分を安定したバイオ炭中に保持する。それは土壌中で数千年持続できる。バイオ炭は酸性土壌の土壌肥沃度を高め、農業生産性を向上させる可能性がある。バイオ炭の生産中には熱が放出され、これはバイオエネルギーとして利用できる。

湿地

湿地の復元は重要な緩和策である。限られた土地面積で中程度から高い緩和潜在力があり、トレードオフとコストが低い。湿地は気候変動に関して2つの重要な機能を果たす。それらは炭素を隔離し、光合成によって二酸化炭素を固体の植物材料に変換する。また、水を貯蔵し、調節する。湿地は世界的に年間約4500万トンの炭素を貯蔵している。

一部の湿地はメタン排出の重要な発生源である。また、一部は亜酸化窒素も排出する。泥炭地は世界的に陸地の表面のわずか3%を占めるに過ぎない。しかし、最大550ギガトン(Gt)の炭素を貯蔵している。これは全ての土壌炭素の42%を占め、世界の森林を含む他の全ての植生タイプに貯蔵されている炭素を超えている。泥炭地への脅威には、農業のための土地の排水が含まれる。もう一つの脅威は、木材を伐採することであり、木々は泥炭地を保持し固定するのに役立つ。さらに、泥炭はしばしば堆肥として販売される。泥炭地の排水路を塞ぎ、自然植生が回復するのを許すことで、劣化した泥炭地を復元することが可能である。

マングローブ、塩性湿地、アマモは、海洋の植生生息地の大部分を構成している。それらは陸上の植物バイオマスのわずか0.05%に過ぎない。しかし、熱帯林よりも40倍速く炭素を貯蔵する。底引き網漁、沿岸開発のための浚渫、肥料流出は沿岸生息地を損傷させている。特筆すべきことに、過去2世紀で世界のカキ礁の85%が除去された。カキ礁は水を浄化し、他の種の繁殖を助ける。これにより、その地域のバイオマスが増加する。さらに、カキ礁はハリケーンの波の力を弱めることで気候変動の影響を緩和する。また、海面上昇による浸食も軽減する。沿岸湿地の復元は、内陸湿地の復元よりも費用対効果が高いと考えられている。

深海

これらの選択肢は、海洋貯留層が貯蔵できる炭素に焦点を当てている。これには、海洋肥沃化、海洋アルカリ化促進、または強化風化が含まれる。IPCCは2022年に、海洋ベースの緩和策は現在、限定的な展開可能性しか持たないと判断した。しかし、将来の緩和潜在力は大きいと評価した。合計で、海洋ベースの方法は年間1〜100ギガトンのCO2を除去できる可能性があると判断した。そのコストは1トンCO2あたり40〜500米ドル程度である。これらの選択肢のほとんどは、海洋酸性化の削減にも役立つ可能性がある。これは、大気中のCO2濃度増加によって引き起こされるpH値の低下である。

クジラの個体数回復は緩和において役割を果たす可能性がある。なぜならクジラは海洋の栄養塩循環において重要な役割を果たすからである。これは、クジラの液体糞が海洋表面に留まる「クジラポンプ」と呼ばれるものを通じて起こる。植物プランクトンは太陽光を利用して光合成を行うために海洋表面近くに生息しており、糞中の多くの炭素、窒素、鉄に依存している。植物プランクトンが海洋食物連鎖の基盤を形成するため、これにより海洋バイオマスが増加し、それに伴い海洋に隔離される炭素量も増加する。

ブルーカーボン管理は、海洋ベースの生物学的二酸化炭素除去(CDR)のもう一つのタイプである。これは陸上および海洋ベースの対策を含むことができる。この用語は通常、潮汐湿地、マングローブ、アマモが炭素隔離において果たす役割を指す。これらの取り組みの一部は、海洋炭素の大部分が保持されている深海でも行うことができる。これらの生態系は気候変動緩和に貢献できるだけでなく、生態系ベースの適応にも貢献する。逆に、ブルーカーボン生態系が劣化または失われると、炭素が大気中に放出される。ブルーカーボン潜在力の開発への関心が高まっている。科学者たちは、場合によってはこれらのタイプの生態系が陸上林よりもはるかに多くの炭素を単位面積あたり除去することを発見している。しかし、炭素除去ソリューションとしてのブルーカーボンの長期的な有効性については議論が続いている。

強化風化

強化風化は、年間20億から40億トンのCO2を除去できる可能性を秘めた技術である。このプロセスは、天然の風化を加速させることを目的としている。 具体的には、玄武岩のような細かく砕かれたケイ酸塩鉱物を地表に散布する。これにより、岩石、水、空気の間の化学反応が促進される。この反応を通じて、大気中の二酸化炭素が除去され、最終的に固体の炭酸塩鉱物または海洋のアルカリ度として永久的に貯蔵される。

CO2を回収・貯蔵するその他の方法

大気中の二酸化炭素(CO2)を除去する伝統的な陸上ベースの方法に加えて、他の技術も開発中である。これらはCO2排出量を削減し、既存の大気中CO2濃度を低下させる可能性がある。炭素回収・貯留(CCS)は、セメント工場やバイオマス発電所などの大規模な点源からCO2を回収し、大気中に放出せずに安全に貯蔵することで気候変動を緩和する方法である。IPCCは、CCSなしでは地球温暖化を食い止めるコストが倍増すると推定している。

太陽放射管理とともに検討されている最も有望な二酸化炭素除去方法の中でも、バイオ炭土壌改良はすでに商業的に展開されている。研究によると、バイオ炭に含まれる炭素は土壌中で数世紀にわたって安定しており、年間ギガトンのCO2を除去する持続的な潜在力がある。専門家の評価では、バイオ炭によるCO2除去の正味費用は1トンあたり30〜120米ドルである。市場データによると、2023年に供給された耐久性のある炭素除去クレジットの94%がバイオ炭によるものであり、現在の拡張性を示している。一方、成層圏エーロゾル注入(SAI)は、成層圏に硫酸塩エーロゾルを散布することで地球の温度を迅速に低下させる可能性がある。しかし、気候変動に関連する規模での展開には、新しい高高度航空機の設計と認証が必要であり、そのプロセスには10年以上かかると推定され、冷却温度1度あたり年間約180億米ドルの継続的な運用コストがかかる。モデルはSAIが地球の平均気温を低下させることを確認しているが、オゾン層破壊、地域的な降水パターンの変化、プログラムが中断された場合の突然の「終端ショック」による温暖化のリスクなど、潜在的な副作用がある。これらの全身的なリスクはバイオ炭の展開にはない。

バイオエネルギーと炭素回収・貯蔵(BECCS)は、CCSの潜在能力を拡張し、大気中CO2濃度を低下させることを目的としている。このプロセスは、バイオエネルギーのために栽培されたバイオマスを使用する。バイオマスは、燃焼、発酵、または熱分解によるバイオマスの消費を通じて、電力、熱、バイオ燃料などの有用な形態のエネルギーを生成する。このプロセスは、バイオマスが成長する際に大気から取り込まれたCO2を回収する。その後、地下に貯蔵するか、バイオ炭として土地に適用する。これにより、大気から効果的に除去される。これはBECCSを負の排出技術(NET)にする。

科学者たちは2018年にBECCSからの負の排出量の潜在的な範囲を年間0〜22ギガトンと推定した。2022年時点で、BECCSは年間約200万トンのCO2を回収していた。バイオマスのコストと入手可能性がBECCSの広範な展開を制限している。BECCSは現在、統合評価モデル(IAM)など、IPCCプロセスに関連するモデリングにおいて、2050年以降の気候目標達成の大部分を占めている。しかし、生物多様性の損失のリスクがあるため、多くの科学者は懐疑的である。

直接空気回収は、周囲の空気から直接CO2を回収するプロセスである。これは、点源から炭素を回収するCCSとは対照的である。それは、隔離、利用、またはカーボンニュートラル燃料やウィンドガスの生産のために濃縮されたCO2の流れを生成する。

セクター別緩和

建物

建築部門は世界のエネルギー関連CO

2排出量の23%を占める。エネルギーの約半分は暖房と給湯に使われている。建物の断熱は、一次エネルギー需要を大幅に削減できる。ヒートポンプの負荷は、変動性再生可能エネルギー源を系統に統合するためのデマンドレスポンスに参加できる柔軟な資源も提供する可能性がある。太陽熱温水器は熱エネルギーを直接利用する。充足策には、世帯のニーズの変化に応じてより小さな家に移ること、空間の複合利用、機器の共有利用などがある。計画者や土木工学者は、パッシブソーラー建築設計、低エネルギー建築、またはゼロエネルギー建築技術を使用して新しい建物を建設できる。さらに、都市部の開発において、より明るい色で反射率の高い材料を使用することで、よりエネルギー効率良く冷房できる建物を設計することが可能である。

ヒートポンプは建物を効率的に暖房し、空調によって冷房する。現代のヒートポンプは通常、消費される電気エネルギーの約3〜5倍の熱エネルギーを輸送する。その量は成績係数と外気温に依存する。

冷凍と空調は、化石燃料ベースのエネルギー生産とフッ素化ガスの使用によって引き起こされる世界のCO

2排出量の約10%を占める。パッシブクーリング建築設計や受動型日中放射冷却表面などの代替冷却システムは、空調の使用を削減できる。暑く乾燥した気候の郊外や都市は、日中放射冷却により冷房からのエネルギー消費を大幅に削減できる。

貧しい国々での熱の上昇と機器の普及により、冷房のためのエネルギー消費量は大幅に増加する可能性が高い。世界で最も暑い地域に住む28億人のうち、現在エアコンを所有しているのはわずか8%に過ぎないが、米国と日本では90%の人が所有している。エネルギー効率の改善と、空調のための電力の脱炭素化を、超汚染性の冷媒からの転換と組み合わせることで、世界は今後40年間で累積的に最大210〜460 GtCO2-eqの温室効果ガス排出量を回避できる可能性がある。冷却部門における再生可能エネルギーへの移行には2つの利点がある。日中にピークを迎える太陽エネルギー生産は冷却に必要な負荷と一致し、さらに、冷却は電力系統における負荷管理の大きな可能性を秘めている。

都市計画

都市は2020年に、商品やサービスの生産と消費から発生するCO2とCH

4を合わせて28ギガトン(GtCO2-eq)排出した。気候スマートな都市計画は、移動距離を減らすために都市の無秩序な拡大を抑制することを目指している。これにより、輸送からの排出量が削減されます。歩行可能性と自転車インフラを改善して自動車から切り替えることは、国全体の経済にとって有益である。

都市林業、湖、その他のブルー・グリーンインフラは、冷房のエネルギー需要を削減することで、直接的および間接的に排出量を削減できる。都市固形廃棄物からのメタン排出量は、分別、堆肥化、リサイクルによって削減できる。

輸送

輸送は世界の排出量の15%を占めている。公共交通機関、低炭素貨物輸送、および自転車の利用を増やすことは、輸送の脱炭素化の重要な要素である。

電気自動車と環境に優しい鉄道は、化石燃料の消費を削減するのに役立つ。ほとんどの場合、電気鉄道は航空輸送やトラック輸送よりも効率的である。その他の効率化手段には、公共交通機関の改善、スマートモビリティ、カーシェアリング、電気ハイブリッド車などがある。乗用車の化石燃料は排出量取引に含めることができる。さらに、自動車に支配された輸送システムから、低炭素の先進的な公共交通システムへと移行することが重要である。

重量があり大型の自家用車(自動車など)は、移動に多くのエネルギーを必要とし、都市空間を大きく占める。これらを代替するいくつかの交通手段が利用可能である。欧州連合は欧州グリーンディールの一環としてスマートモビリティを位置づけている。スマートシティにおいても、スマートモビリティは重要である。

世界銀行は、低所得国が電気バスを購入するのを支援している。購入価格はディーゼルバスよりも高いが、運行コストの低さや、空気がきれいになることによる健康改善が、この高い価格を相殺することができる。

2050年までに、走行中の自動車の4分の1から4分の3が電気自動車になると予測されている。水素は、バッテリーだけでは重すぎる場合、長距離の大型貨物トラックの解決策となる可能性がある。

船舶

海運業界では、液化天然ガス(LNG)を船舶用燃料として使用することが、排出規制によって推進されている。船舶運航者は、重油からより高価な石油系燃料に切り替えるか、高価な排ガス処理技術を導入するか、LNGエンジンに切り替える必要がある。メタンがエンジンを通して未燃焼のまま漏れるメタンすべりは、LNGの利点を低下させる。世界最大のコンテナ輸送会社であり船舶運航会社であるマースクは、LNGのような移行期の燃料への投資における座礁資産について警告している。同社は、グリーンアンモニアを将来の好ましい燃料タイプの一つとして挙げている。同社は、カーボンニュートラルなメタノールで稼働する初のカーボンニュートラルな船舶を2023年までに就航させると発表した。クルーズ客船運航会社は、部分的に水素動力船を試験運用している。

ハイブリッドおよび全電動フェリーは短距離に適している。ノルウェーの目標は、2025年までに全電動船隊とすることである。

航空輸送

ジェット旅客機は、二酸化炭素、窒素酸化物、飛行機雲、粒子状物質を排出することで気候変動に寄与している。それらの放射強制力は、CO

2単独の場合の1.3〜1.4倍と推定されており、誘発される巻雲は含まれていない。2018年には、世界の商業運航が全CO2排出量の2.4%を生成した。

航空業界は燃費効率を向上させてきたが、航空輸送量が増加したため、総排出量は増加している。2020年までに、航空排出量は2005年よりも70%高く、2050年までに300%増加する可能性がある。

航空の環境フットプリントは、航空機の燃料効率を向上させることで削減できる。窒素酸化物、粒子状物質、飛行機雲による非CO

2気候影響を低減するために、飛行ルートを最適化することも役立つ。航空バイオ燃料、炭素排出権取引、炭素オフセット(191カ国が参加するICAOの国際航空のためのカーボンオフセットおよび削減スキーム(CORSIA)の一部)は、CO2排出量を削減できる。短距離飛行禁止、鉄道接続、個人的な選択、航空機への課税と補助金は、フライト数を減らすことにつながる。ハイブリッド電気航空機や電気航空機、または水素動力航空機が化石燃料動力航空機に取って代わる可能性がある。

専門家は、航空からの排出量が、少なくとも2040年まではほとんどの予測で増加すると予想している。これらは現在、CO

2換算で180Mt、または輸送排出量の11%に相当する。航空バイオ燃料と水素は、今後数年間でごく一部のフライトしかカバーできない。専門家は、ハイブリッド駆動航空機が2030年以降に商業地域定期便を開始すると予想している。バッテリー駆動航空機は2035年以降に市場に投入される可能性が高い。CORSIAの下では、運航会社は2019年レベルを超える排出量をカバーするために炭素オフセットを購入できる。CORSIAは2027年から義務化される。

農業、林業、土地利用

温室効果ガス排出量のほぼ20%は農業と林業部門から発生している。これらの排出量を大幅に削減するには、農業部門への年間投資額を2030年までに2600億ドルに増やす必要がある。これらの投資による潜在的利益は2030年までに4.3兆ドルと推定されており、16対1という実質的な経済的リターンをもたらす。

フードシステムにおける緩和策は、4つのカテゴリーに分けられる。これらは需要側の変化、生態系保護、農場での緩和、およびサプライチェーンにおける緩和である。需要側では、食品廃棄物を制限することが食品排出量を削減する効果的な方法である。植物ベースの食事など、動物性食品への依存度が低い食事への変更も効果的である。

世界のメタン排出量の21%を占める牛は、地球温暖化の主要な要因である。熱帯雨林が伐採され、土地が放牧用に転換されると、その影響はさらに大きくなる。ブラジルでは、牛肉1kgの生産により最大335kgのCO2換算排出量が生じる可能性がある。 他の家畜、糞尿管理、稲作も、農業における化石燃料燃焼に加えて温室効果ガスを排出する。

家畜からの温室効果ガス排出量を削減するための重要な緩和策には、遺伝子選抜、メタン酸化細菌の第一胃への導入、飼料の変更、放牧管理などがある。その他の選択肢としては、反芻動物を含まない代替品、例えば植物性ミルクや代替肉への食事の変更がある。家禽のような非反芻動物の家畜は、はるかに少ない温室効果ガスを排出する。

稲作におけるメタン排出量は、水管理の改善、乾燥種まきと一度の排水の組み合わせ、または間断灌漑を実行することによって削減可能である。これにより、湛水と比較して最大90%の排出量削減が可能となり、収量も増加する。

栄養管理を通じて窒素肥料の使用を削減することで、2020年から2050年までに2.77〜11.48ギガトンの二酸化炭素に相当する亜酸化窒素排出量を回避できる可能性がある。

産業

直接排出と間接排出を含めると、産業は温室効果ガスの最大の排出源である。電化は産業からの排出量を削減できる。電力が選択肢とならないエネルギー多消費産業においては、グリーン水素が主要な役割を果たすことができる。さらなる緩和策としては、鉄鋼業やセメント産業がより汚染の少ない生産プロセスに切り替えることが挙げられる。排出原単位を削減するために製品をより少ない材料で作ることができ、産業プロセスをより効率的にすることもできる。最後に、循環経済の措置は新規材料の必要性を減らす。これは、それらの材料の採掘や収集から放出されていたであろう排出量も削減する。

セメント生産の脱炭素化には新しい技術が必要であり、したがってイノベーションへの投資が必要である。しかし、緩和のための技術はまだ成熟していない。そのため、少なくとも短期的にはCCSが必要となるだろう。

もう一つの大きなカーボンフットプリントを持つセクターは鉄鋼業であり、世界の排出量の約7%を占めている。排出量は、電弧炉を使用してスクラップ鋼を溶融しリサイクルすることで削減できる。排出なしでバージンスチールを生産するには、高炉を水素直接還元鉄と電弧炉に置き換えることができる。あるいは、炭素回収・貯留ソリューションを使用することも可能である。

石炭、天然ガス、石油の生産には、しばしば重大なメタン漏洩が伴う。2020年代初頭、一部の政府はこの問題の規模を認識し、規制を導入した。油井やガス井、処理施設におけるメタン漏洩は、ガスを国際的に容易に取引できる国では費用対効果の高い解決策である。イランやトルクメニスタンなどガスが安価な国では漏洩が発生している。そのほとんどは、古い部品の交換や定常的なフレアリングの防止によって止めることができる。炭層メタンは、炭鉱が閉鎖された後でも漏洩し続ける可能性がある。しかし、それは排水や換気システムによって回収することができる。化石燃料企業は、メタン漏洩に対処するための財政的インセンティブを常に持っているわけではない。

コベネフィット

気候変動緩和のコベネフィットは、「付随的便益」とも呼ばれ、科学文献では当初、温室効果ガス排出量の削減がいかに大気質を改善し、その結果、人間の健康に良い影響を与えるかについて記述した研究が主流であった。コベネフィット研究の範囲は、その経済的、社会的、生態学的、政治的意味合いにまで拡大した。

気候緩和および適応策から生じるポジティブな二次的効果は、1990年代から研究で言及されてきた。IPCCは2001年に初めてコベネフィットの役割に言及し、その後の第4次および第5次評価サイクルでは、労働環境の改善、廃棄物の削減、健康上の利益、設備投資の削減を強調した。

IPCCは2007年に「温室効果ガス緩和のコベネフィットは、政策立案者が行う分析において重要な決定基準となりうるが、しばしば無視されている」と指摘し、コベネフィットは「企業や意思決定者によって、定量化、貨幣化、あるいは特定さえされていない」と付け加えた。コベネフィットを適切に考慮することで、「緩和行動のタイミングとレベルに関する政策決定に大いに影響を与える」ことができ、「国民経済と技術革新に大きな利益がある」可能性がある。

英国における気候変動対策の分析では、公衆衛生上の利益が、気候変動対策から得られる総利益の主要な構成要素であることが判明した。

雇用と経済発展

コベネフィットは、雇用、産業発展、国家のエネルギー独立性、および自家消費に良い影響を与える可能性がある。再生可能エネルギーの導入は、雇用機会を育成できる。国や導入シナリオにもよるが、石炭火力発電所を再生可能エネルギーに置き換えることで、平均MWあたりの雇用数を2倍以上に増やすことができる。特に太陽エネルギーと風力エネルギーへの再生可能エネルギーへの投資は、生産の価値を高めることができる。エネルギー輸入に依存している国々は、再生可能エネルギーを導入することでエネルギー独立性を高め、供給安定性を確保できる。再生可能エネルギーからの国内エネルギー生産は化石燃料輸入の需要を低下させ、年間の経済的節約を拡大する。

欧州委員会は、2030年までに水素生産で18万人、太陽光発電で6万6千人の熟練労働者の不足を予測している。

エネルギー安全保障

再生可能エネルギーのシェアを高めることは、さらにエネルギー安全保障を高めることにつながる。農村部におけるエネルギーアクセスや農村部の生計改善など、社会経済的コベネフィットが分析されている。完全に電化されていない農村部は、再生可能エネルギーの導入から恩恵を受けることができる。太陽光発電によるミニグリッドは、経済的に存続可能で、費用対効果が高く、停電の回数を減らすことができる。エネルギーの信頼性には追加的な社会的な影響がある。安定した電力は教育の質を向上させる。

国際エネルギー機関(IEA)はエネルギー効率の「多重便益アプローチ」を明示し、国際再生可能エネルギー機関(IRENA)は再生可能エネルギー部門のコベネフィットのリストを具体化した。

健康と福祉

気候変動緩和による健康上の利益は大きい。潜在的な対策は、気候変動による将来の健康影響を緩和するだけでなく、直接的に健康を改善することもできる。気候変動緩和は、大気汚染の削減など、様々な健康上のコベネフィットと相互に関連している。化石燃料燃焼によって発生する大気汚染は、地球温暖化の主要な要因であると同時に、年間多数の死者の原因でもある。一部の推定では、2018年には870万人もの過剰死があったとされる。2023年の研究では、心臓発作、脳卒中、慢性閉塞性肺疾患などの病気を引き起こすことで、2019年時点で化石燃料が毎年500万人以上の命を奪っていると推定されている。粒子状大気汚染が圧倒的に多くの死者を出し、次いで地上オゾンが続く。

緩和政策は、赤身肉の少ないより健康的な食事、より活動的なライフスタイル、都市の緑地への接触機会の増加なども促進できる。都市の緑地へのアクセスはメンタルヘルスにも利益をもたらす。グリーンインフラとブルーインフラの利用増加は、都市のヒートアイランド現象を軽減できる。これにより、人々の熱ストレスが軽減される。

気候変動適応

一部の緩和策は、気候変動適応の分野でコベネフィットを持つ。これは、例えば多くの自然を活用した解決策の場合に当てはまる。都市の文脈での例としては、緩和と適応の両方の利益を提供する都市のグリーン・ブルーインフラが含まれる。これは、都市林や街路樹、緑化屋根、壁面緑化、都市農業などの形をとることができる。緩和は、炭素吸収源の保全と拡大、および建物のエネルギー使用量の削減によって達成される。適応の利益は、例えば熱ストレスの軽減や洪水リスクの軽減によってもたらされる。

負の副作用

緩和策は、負の副作用とリスクを伴うこともある。農業と林業において、緩和策は生物多様性や生態系の機能に影響を与える可能性がある。再生可能エネルギーにおいては、金属や鉱物の採掘が保護地域への脅威を増加させる可能性がある。太陽光パネルや電子廃棄物のリサイクル方法に関する研究も行われている。これにより、材料の供給源が確保され、採掘の必要がなくなるだろう。

学者たちは、緩和策のリスクと負の副作用に関する議論が、行き詰まりや、行動を起こす上での克服不可能な障壁があるという感覚につながる可能性があることを発見した。

費用と資金

気候変動の影響緩和費用は、いくつかの要因によって変動する。一つはベースラインであり、これは代替の緩和シナリオと比較される参照シナリオである。その他には、費用がどのようにモデル化されるか、および将来の政府政策に関する仮定がある。特定の地域における緩和の費用推定は、将来その地域に許容される排出量の量、ならびに介入のタイミングに依存する。

緩和費用は、排出量がどのように、そしていつ削減されるかによって異なる。早期の周到な計画的行動は、費用を最小限に抑えるだろう。世界的に見ると、温暖化を2℃未満に抑えることによる利益は費用を上回るとされており、エコノミストによれば、それは手頃な費用である。

経済学者たちは、気候変動緩和の費用をGDPの1%から2%と推定している。これは多額ではあるが、政府が苦境にある化石燃料産業に提供している補助金よりははるかに少ない。国際通貨基金はこれを年間5兆ドル以上と推定している。

別の推定では、気候変動緩和と適応のための資金フローは年間8000億ドル以上になるだろうと述べている。これらの財政的要件は、2030年までに年間4兆ドルを超えると予測されている。

世界的に見て、温暖化を2℃に制限することは、経済的費用よりも高い経済的利益をもたらす可能性がある。緩和の経済的影響は、政策設計と国際協力のレベルに応じて、地域や家計間で大きく異なる。世界的な協力の遅れは、地域全体、特に現在比較的炭素集約度が高い地域において、政策コストを増加る。統一的な炭素価値を持つ経路は、より炭素集約的な地域、化石燃料輸出国、および貧しい地域でより高い緩和費用を示す。GDPや金銭的用語で表現された集計的な定量化は、貧しい国の家計への経済的影響を過小評価している。福利と幸福に対する実際の影響は、比較的に大きい。

費用便益分析は、気候変動緩和全体を分析するには不適切かもしれない。しかし、1.5℃目標と2℃目標の違いを分析するには依然として有用である。排出量を削減するコストを推定する方法の一つは、潜在的な技術的および生産の変化の可能性のあるコストを考慮することである。政策立案者は、様々な方法の限界削減費用を比較して、時間の経過に伴う可能な削減のコストと量を評価できる。様々な措置の限界削減費用は、国、セクター、および時間によって異なる。

輸入のみに対するエコ関税は、世界的な輸出の競争力の低下と脱工業化に貢献する。

気候変動の影響によるコストの回避

気候変動の影響を限定することで、気候変動によるコストの一部を回避することが可能である。スターン・レビューによると、行動しない場合、現在そして未来永劫、毎年世界のGDPの少なくとも5%に相当する損失を被る可能性がある。より広範なリスクと影響を含めると、これはGDPの20%以上になることもある。しかし、気候変動を緩和するコストは、GDPの約2%に過ぎない。また、温室効果ガス排出量の大幅な削減を遅らせることは、財政的な観点からも得策ではないかもしれない。

緩和策は、しばしばコストと温室効果ガス削減の可能性という観点から評価される。しかし、これは人間の幸福に対する直接的な影響を考慮していない。

排出量削減コストの配分

温暖化を2℃以下に抑えるために必要な速度と規模での緩和は、深い経済的・構造的変化を伴う。これらは、地域、所得階級、部門間で複数の種類の分配上の懸念を引き起こす。

排出量削減の責任をどのように配分するかについては、様々な提案がなされてきた。これらには、平等主義、最低限の消費水準に基づく基本的ニーズ、比例原則、そして汚染者負担原則が含まれる。具体的な提案の一つに「一人当たり均等配分」がある。このアプローチには2つのカテゴリーがある。最初のカテゴリーでは、排出量が国家人口に応じて配分される。2番目のカテゴリーでは、排出量が歴史的または累積的な排出量を考慮しようとする方法で配分される。

融資

経済発展と炭素排出量削減を両立させるために、開発途上国は特に財政的・技術的な支援を必要としている。 IPCCは、このような支援を加速させることで、気候変動に対する財政的・経済的脆弱性における不平等を解決できるとも指摘しています。この目標を達成する一つの方法として、京都議定書のクリーン開発メカニズム(CDM)が挙げられる。

政策

国家政策

気候変動緩和策は、個人や国家の社会経済的地位に大きく複雑な影響を与えうる。これは正負両方の場合がある。政策を適切に設計し、包摂的にすることが重要である。そうしないと、気候変動緩和策が貧困世帯に高い財政的負担を課す可能性がある。

1998年から2022年の間に実施された1,500件の気候政策介入について評価が行われた。この介入は41カ国、6大陸にわたり、2019年時点で世界の総排出量の81%を占めていた。評価の結果、大幅な排出量削減をもたらした63件の成功した介入が判明した。これらの介入によって回避された総CO2排出量は0.6億トンから1.8億メトリックトンであった。この研究は4.5%以上の排出量削減をもたらした介入に焦点を当てたが、研究者たちはパリ協定が要求する削減量を満たすには年間230億メトリックトンが必要であると指摘した。一般的に、炭素価格は先進国で最も効果的であることが判明し、規制は開発途上国で最も効果的であることが判明した。補完的な政策ミックスは相乗効果の恩恵を受け、孤立した政策の実施よりも効果的な介入であることがほとんどであった。

OECDは、国家レベルでの実施に適した48種類の異なる気候緩和政策を認識している。これらは大きく3つのタイプに分類できる:「市場ベース」の手段、「非市場ベース」の手段、および「その他の」政策である。

- 「その他の」政策には、「独立した気候諮問機関の設立」が含まれる。

- 「非市場ベース」の政策には、「規制基準の導入または強化」が含まれる。これらは技術または性能基準を定めるものである。これらは情報の非対称性という市場の失敗に対処するのに効果的である。

- 「市場ベース」の政策の中で、炭素価格が最も効果的であることが判明しており(少なくとも先進国では)、後述の専用の節がある。気候変動緩和のための追加の「市場ベース」の政策手段には以下が含まれる。

「排出税」これらはしばしば、国内の排出者に対し、大気中に排出するCO21トンあたり固定料金または税金を支払うことを要求する。化石燃料採掘からのメタン排出も時折課税される。しかし、農業からのメタンと亜酸化窒素は通常課税されない。

「有害な補助金の撤廃」多くの国が排出に影響を与える活動に補助金を提供している。例えば、多くの国で多額の化石燃料補助金が存在する。化石燃料補助金の段階的廃止は、気候危機に対処するために極めて重要である。しかし、抗議運動や貧困層をさらに貧しくすることを避けるために、慎重に行われる必要がある。

「有益な補助金の創設」補助金や財政的インセンティブの創設。一例は、潮流発電など、まだ商業的に実行可能ではないクリーンな発電を支援するためのエネルギー補助金である。

「排出権取引制度」排出権取引制度は排出量を制限できる。

カーボンプライシング

温室効果ガス排出に追加費用を課すことで、化石燃料の競争力を低下させ、低炭素エネルギー源への投資を加速させることができる。固定された炭素税を課す、または動的な炭素排出権取引(ETS)システムに参加する国が増加している。2021年には、世界の温室効果ガス排出量の21%以上が炭素価格によってカバーされた。これは、中国全国炭素排出権取引スキームの導入により、以前よりも大幅な増加である。

排出量取引制度は、特定の削減目標に対して排出枠を制限する可能性を提供する。しかし、排出枠の過剰供給により、ほとんどのETSは低価格水準の10ドル前後にとどまり、影響は小さい。これには、2021年に7ドル/トンCO2で始まった中国のETSも含まれる。唯一の例外は欧州連合排出量取引制度であり、ここでは価格が2018年に上昇し始め、2022年には約80ユーロ/トンCO2に達した。これにより、排出原単位にもよるが、石炭火力発電で約0.04ユーロ/KWh、ガス火力発電で約0.02ユーロ/KWhの追加費用が発生する。エネルギー要件が高く排出量の多い産業は、しばしば非常に低いエネルギー税しか支払わないか、全く支払わないことが多い。

これは国家スキームの一部であることが多いが、炭素オフセットとクレジットは、国際市場のような自主的な市場の一部となることもできる。特に、アラブ首長国連邦のBlueカーボン社は、炭素クレジットと引き換えに、イギリスに匹敵する面積の土地を保全するために所有権を購入した。

国際協定

国際協力は、気候変動対策にとって「極めて重要な推進力」であると考えられている。ほとんど全ての国が国際連合気候変動枠組条約(UNFCCC)の締約国である。UNFCCCの究極の目的は、温室効果ガスの大気中濃度を、気候システムに対する危険な人為的干渉を防ぐ水準で安定させることである。

モントリオール議定書は、その本来の目的ではありませんでしたが、気候変動緩和の取り組みに恩恵をもたらしました。この国際条約は、CFCなどのオゾン層破壊物質の排出量を削減することに成功した。

パリ協定

歴史

歴史的に、気候変動に対処する努力は多国間レベルで行われてきた。これらは、国際連合気候変動枠組条約(UNFCCC)の下で、国連におけるコンセンサス決定に達する試みを含んでいる。これは、世界的な公共問題に対してできるだけ多くの国際政府を行動に参加させるという、歴史的に支配的なアプローチである。1987年のモントリオール議定書は、このアプローチが機能しうるという先例である。しかし、一部の批評家は、UNFCCCのコンセンサスアプローチのみを利用するトップダウン型枠組みは非効果的だと述べている。彼らはボトムアップ型ガバナンスの対案を提示している。同時に、これはUNFCCCへの重点を軽減するだろう。

1997年に採択されたUNFCCCの京都議定書は、「付属書I」国に対する法的拘束力のある排出削減コミットメントを定めた。議定書は、付属書I国が排出削減コミットメントを達成するために使用できる3つの国際政策手段(「柔軟性メカニズム」)を定義した。バシュマコフによると、これらの手段の使用は、付属書I国が排出削減コミットメントを達成するためのコストを大幅に削減できる可能性がある。

2015年に締結されたパリ協定は、2020年に期限切れとなった京都議定書の後継である。京都議定書を批准した国々は、二酸化炭素および他の5つの温室効果ガスの排出量を削減するか、これらのガスの排出量を維持または増加させる場合は炭素排出権取引を行うことをコミットした。

2015年、UNFCCCの「構造化専門家対話」は、「一部の地域や脆弱な生態系では、1.5℃を超える温暖化でも高いリスクが予測される」という結論に達した。最も貧しい国々や太平洋の島嶼国家の強い外交的声と相まって、この専門家の知見は、2015年のパリ気候会議の決定を推進する原動力となり、既存の2℃目標に加えてこの1.5℃の長期目標を掲げることになった。

障壁

2排出量の分布

気候変動緩和策を達成するには、個人、制度、市場の障壁が存在する。これらは、さまざまな緩和策、地域、社会によって異なる。

二酸化炭素除去の会計に関する困難は、経済的障壁となりうる。これはBECCS(バイオエネルギーと炭素回収・貯留)に当てはまる。企業がとる戦略も障壁となりうるが、脱炭素化を加速させることもできる。

社会を脱炭素化するためには、国家が主導的な役割を果たす必要がある。これは、大規模な調整努力が必要だからである。この強力な政府の役割は、社会凝集性、政治的安定性、信頼がある場合にのみうまく機能する。

陸上ベースの緩和策にとって、金融は大きな障壁である。その他の障壁としては、文化的価値観、ガバナンス、説明責任、制度的能力が挙げられる。

発展途上国は、緩和に関してさらなる障壁に直面している。

- 2020年代初頭に資本コストが増加した。利用可能な資本と資金の不足は、発展途上国では一般的である。規制基準の欠如と相まって、この障壁は非効率な設備の拡散を助長している。

- これらの国の多くには、財政的および能力の障壁も存在する。

ある研究では、気候関連研究への総資金のわずか0.12%しか気候変動緩和の社会科学に向けられていないと推定されている。はるかに多くの資金が気候変動に関する自然科学研究に向けられている。また、気候変動の影響とその適応に関する研究にもかなりの金額が費やされている。

社会と文化

コミットメントを売却する

8兆米ドル相当の投資を持つ1000以上の組織が、化石燃料からの投資撤退をコミットしている。社会的責任投資ファンドは、投資家が高い環境・社会・企業統治(ESG)基準を満たすファンドに投資することを可能にする。

COVID-19パンデミックの影響

COVID-19パンデミックは、一部の政府が気候変動対策から、少なくとも一時的に焦点を移す原因となった。この環境政策への障害は、グリーンエネルギー技術への投資減速の一因となった可能性がある。COVID-19による経済活動の停滞も、この影響をさらに大きくした。

2020年には、世界の二酸化炭素排出量が6.4%、つまり23億トン減少した。しかし、パンデミック中に多くの国が制限を解除し始めると、温室効果ガス排出量はその後反発した。パンデミック政策の直接的な影響は、気候変動に対する長期的な影響としてはごくわずかであった。

国別の事例

米国

アメリカ合衆国政府は、温室効果ガス排出量への対応に関して態度を変化させてきた。ジョージ・W・ブッシュ政権は京都議定書に署名しないことを選択したが、オバマ政権はパリ協定に加盟した。トランプ政権はパリ協定から脱退し、原油とガスの輸出を増加させ、米国を最大の生産国とした。

2021年、バイデン政権は、2030年までに排出量を2005年レベルの半分に削減することを約束した。2022年には、バイデン大統領がインフレ削減法に署名し、これは気候変動対策として10年間で約3750億ドルを提供すると推定されている。2022年現在、炭素の社会的費用は1トンあたり51ドルであるが、学術界では3倍以上であるべきだとされている。中国

中国は、2030年までに排出量をピークアウトさせ、2060年までにネットゼロを達成することを公約している。しかし、中国の石炭火力発電所が(炭素回収なしで)2045年以降も稼働し続ける場合、地球温暖化を1.5℃に抑えることは不可能であるとされている。このような状況の中、中国では中国全国炭素排出権取引スキームが2021年に開始された。

欧州連合

欧州委員会は、欧州連合がFit-for-55の脱炭素化目標を達成するためには、年間4億7,700万ユーロの追加投資が必要だと試算している。

欧州連合(EU)では、政府主導の政策、特に欧州グリーンディールが、グリーンテック分野をベンチャーキャピタル投資の重要な領域として位置づける上で大きな役割を果たしました。その結果、2023年までにEUのグリーンテック分野へのベンチャーキャピタル投資額は米国と同水準に達しました。これは、的を絞った資金援助を通じて、イノベーションを推進し、気候変動緩和に取り組むというEUの強い意志を反映しています。 欧州グリーンディールが推進する政策は、2021年から2023年の間に、EUのグリーンテック企業へのベンチャーキャピタル投資が30%増加するという結果に貢献しました。これは、同時期に他のセクターで景気後退が見られた中での特筆すべき成果です。

EUにおけるベンチャーキャピタル投資総額は、依然として米国よりも約6倍低いものの、グリーンテック分野ではこの差が大幅に縮まり、多額の資金が流入している。 特に投資が増加している主要分野は、エネルギー貯蔵、循環経済に関する取り組み、そして農業技術です。これは、EUが2030年までに温室効果ガス排出量を少なくとも55%削減するという野心的な目標を掲げていることにも後押しされている。

関連するアプローチ

日射管理(SRM)との関係

日射管理(SRM)は地表温度を低下させる可能性があるが、それは温室効果ガスという根本原因に対処するのではなく、一時的に気候変動を隠蔽するに過ぎない。SRMは、地球が吸収する太陽放射の量を変化させることで機能する。例としては、地表に到達する日光の量を減らすこと、雲の光学的厚さと寿命を減らすこと、および地表が放射を反射する能力を変えることなどが挙げられる。IPCCは、SRMを気候緩和の選択肢ではなく、気候リスク低減戦略または補完的な選択肢として記述している。

この分野の用語はまだ進化中である。専門家は、CDRまたはSRMの技術が地球規模で使用される場合、科学文献において「ジオエンジニアリング」または「気候工学」という用語を用いることがある。IPCCの報告書では、「ジオエンジニアリング」または「気候工学」という用語はもはや使用されていない。

関連項目

参考資料

| この記事は、クリエイティブ・コモンズ・表示・継承ライセンス3.0のもとで公表されたウィキペディアの項目Climate change mitigation(11 July 2025, at 22:21編集記事参照)を翻訳して二次利用しています。 |