フラビンアデニンジヌクレオチド

Flavin adenine dinucleotide/ja

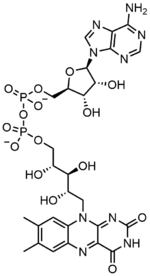

生化学において、フラビンアデニンジヌクレオチド(FAD)は、様々なタンパク質に付随する酸化還元活性の補酵素であり、代謝におけるいくつかの酵素反応に関与する。フラボタンパク質はフラビン基を持つタンパク質であり、FADまたはフラビンモノヌクレオチド(FMN)の形をとる。コハク酸デヒドロゲナーゼ複合体の構成要素、α-ケトグルタル酸デヒドロゲナーゼ、ピルビン酸デヒドロゲナーゼ複合体の構成要素など、多くのフラボタンパク質が知られている。

| |

| |

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| 3DMet | |

| 1208946 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| DrugBank | |

| EC Number |

|

| 108834 | |

| KEGG | |

| MeSH | Flavin-Adenine+Dinucleotide |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C27H33N9O15P2 | |

| Molar mass | 785.557 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | White, vitreous crystals |

| log P | -1.336 |

| Acidity (pKa) | 1.128 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 12.8689 |

FADは、フラビン-N(5)-オキシド、キノン、セミキノン、ヒドロキノンの4つの酸化還元状態で存在することができる。FADは電子を受容したり供与したりすることによって、これらの状態の間で変換される。FADは完全に酸化された形、すなわちキノン形では、2個の電子と2個のプロトンを受け入れてFADH2(ハイドロキノン形)となる。セミキノン(FADH-)は、FADの還元か、FADH2の酸化のどちらかによって、それぞれ1個の電子と1個のプロトンを受容するか供与することで形成される。しかし、タンパク質によっては、フラビン補因子の過酸化型、フラビン-N(5)-オキシドを生成し、維持するものもある。

歴史

フラボタンパク質は、1879年に牛乳の成分を分離することによって初めて発見された。当初はその乳由来と黄色の色素からラクトクロムと呼ばれていた。科学界が黄色い色素の原因分子を特定するのに実質的な進歩を遂げるには50年かかった。1930年代には、多くのフラビンとニコチンアミドの誘導体構造が発表され、酸化還元触媒反応におけるそれらの義務的な役割が明らかになり、補酵素の研究分野が始まった。ドイツの科学者オットー・ヴァールブルクとウォルター・クリスチャンは1932年に細胞呼吸に必要な酵母由来の黄色いタンパク質を発見した。彼らの同僚ユーゴ・セオレルはこの黄色い酵素をアポ酵素と黄色い色素に分離し、酵素も色素もNADHを酸化する能力がないが、両者を混ぜ合わせると活性が回復することを示した。テオレルは1937年にこの色素がリボフラビンのリン酸エステルであることを確認した(フラビンモノヌクレオチド(FMN))。それは、酵素補因子の最初の直接的な証拠となった。ワールブルグとクリスチャンは、1938年にも同様の実験を行い、FADがD-アミノ酸オキシダーゼの補因子であることを発見した。ニコチンアミドをヒドリド基転移に結びつけたワールブルグの仕事とフラビンの発見は、40年代から50年代にかけて多くの科学者が大量の酸化還元生化学を発見し、クエン酸サイクルやATP合成などの経路でそれらを結びつける道を開いた。

特性

FAD can be reduced to FADH2 through the addition of 2 H+ and 2 e−. FADH2 can also be oxidized by the loss of 1 H+ and 1 e− to form FADH. The FAD form can be recreated through the further loss of 1 H+ and 1 e−. FAD formation can also occur through the reduction and dehydration of flavin-N(5)-oxide. Based on the oxidation state, flavins take specific colors when in aqueous solution. flavin-N(5)-oxide (superoxidized) is yellow-orange, FAD (fully oxidized) is yellow, FADH (half reduced) is either blue or red based on the pH, and the fully reduced form is colorless. Changing the form can have a large impact on other chemical properties. For example, FAD, the fully oxidized form is subject to nucleophilic attack, the fully reduced form, FADH2 has high polarizability, while the half reduced form is unstable in aqueous solution.FAD is an aromatic ring system, whereas FADH2 is not. This means that FADH2 is significantly higher in energy, without the stabilization through resonance that the aromatic structure provides. FADH2 is an energy-carrying molecule, because, once oxidized it regains aromaticity and releases the energy represented by this stabilization.

The spectroscopic properties of FAD and its variants allows for reaction monitoring by use of UV-VIS absorption and fluorescence spectroscopies. Each form of FAD has distinct absorbance spectra, making for easy observation of changes in oxidation state. A major local absorbance maximum for FAD is observed at 450 nm, with an extinction coefficient of 11,300 M−1 cm−1. Flavins in general have fluorescent activity when unbound (proteins bound to flavin nucleic acid derivatives are called flavoproteins). This property can be utilized when examining protein binding, observing loss of fluorescent activity when put into the bound state. Oxidized flavins have high absorbances of about 450 nm, and fluoresce at about 515-520 nm.

Chemical states

In biological systems, FAD acts as an acceptor of H+ and e− in its fully oxidized form, an acceptor or donor in the FADH form, and a donor in the reduced FADH2 form. The diagram below summarizes the potential changes that it can undergo.

Along with what is seen above, other reactive forms of FAD can be formed and consumed. These reactions involve the transfer of electrons and the making/breaking of chemical bonds. Through reaction mechanisms, FAD is able to contribute to chemical activities within biological systems. The following pictures depict general forms of some of the actions that FAD can be involved in.

Mechanisms 1 and 2 represent hydride gain, in which the molecule gains what amounts to be one hydride ion. Mechanisms 3 and 4 radical formation and hydride loss. Radical species contain unpaired electron atoms and are very chemically active. Hydride loss is the inverse process of the hydride gain seen before. The final two mechanisms show nucleophilic addition and a reaction using a carbon radical.

Biosynthesis

FAD plays a major role as an enzyme cofactor along with flavin mononucleotide, another molecule originating from riboflavin. Bacteria, fungi and plants can produce riboflavin, but other eukaryotes, such as humans, have lost the ability to make it. Therefore, humans must obtain riboflavin, also known as vitamin B2, from dietary sources. Riboflavin is generally ingested in the small intestine and then transported to cells via carrier proteins. Riboflavin kinase (EC 2.7.1.26) adds a phosphate group to riboflavin to produce flavin mononucleotide, and then FAD synthetase attaches an adenine nucleotide; both steps require ATP. Bacteria generally have one bi-functional enzyme, but archaea and eukaryotes usually employ two distinct enzymes. Current research indicates that distinct isoforms exist in the cytosol and mitochondria. It seems that FAD is synthesized in both locations and potentially transported where needed.

Function

Flavoproteins utilize the unique and versatile structure of flavin moieties to catalyze difficult redox reactions. Since flavins have multiple redox states they can participate in processes that involve the transfer of either one or two electrons, hydrogen atoms, or hydronium ions. The N5 and C4a of the fully oxidized flavin ring are also susceptible to nucleophilic attack. This wide variety of ionization and modification of the flavin moiety can be attributed to the isoalloxazine ring system and the ability of flavoproteins to drastically perturb the kinetic parameters of flavins upon binding, including flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD).

The number of flavin-dependent protein encoded genes in the genome (the flavoproteome) is species dependent and can range from 0.1% - 3.5%, with humans having 90 flavoprotein encoded genes. FAD is the more complex and abundant form of flavin and is reported to bind to 75% of the total flavoproteome and 84% of human encoded flavoproteins. Cellular concentrations of free or non-covalently bound flavins in a variety of cultured mammalian cell lines were reported for FAD (2.2-17.0 amol/cell) and FMN (0.46-3.4 amol/cell).

FAD has a more positive reduction potential than NAD+ and is a very strong oxidizing agent. The cell utilizes this in many energetically difficult oxidation reactions such as dehydrogenation of a C-C bond to an alkene. FAD-dependent proteins function in a large variety of metabolic pathways including electron transport, DNA repair, nucleotide biosynthesis, beta-oxidation of fatty acids, amino acid catabolism, as well as synthesis of other cofactors such as CoA, CoQ and heme groups. One well-known reaction is part of the citric acid cycle (also known as the TCA or Krebs cycle); succinate dehydrogenase (complex II in the electron transport chain) requires covalently bound FAD to catalyze the oxidation of succinate to fumarate by coupling it with the reduction of ubiquinone to ubiquinol. The high-energy electrons from this oxidation are stored momentarily by reducing FAD to FADH2. FADH2 then reverts to FAD, sending its two high-energy electrons through the electron transport chain; the energy in FADH2 is enough to produce 1.5 equivalents of ATP by oxidative phosphorylation. Some redox flavoproteins non-covalently bind to FAD like Acetyl-CoA-dehydrogenases which are involved in beta-oxidation of fatty acids and catabolism of amino acids like leucine (isovaleryl-CoA dehydrogenase), isoleucine, (short/branched-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase), valine (isobutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase), and lysine (glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase). Additional examples of FAD-dependent enzymes that regulate metabolism are glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (triglyceride synthesis) and xanthine oxidase involved in purine nucleotide catabolism. Noncatalytic functions that FAD can play in flavoproteins include as structural roles, or involved in blue-sensitive light photoreceptors that regulate biological clocks and development, generation of light in bioluminescent bacteria.

Flavoproteins

Flavoproteins have either an FMN or FAD molecule as a prosthetic group, this prosthetic group can be tightly bound or covalently linked. Only about 5-10% of flavoproteins have a covalently linked FAD, but these enzymes have stronger redox power. In some instances, FAD can provide structural support for active sites or provide stabilization of intermediates during catalysis. Based on the available structural data, the known FAD-binding sites can be divided into more than 200 types.

90 flavoproteins are encoded in the human genome; about 84% require FAD, and around 16% require FMN, whereas 5 proteins require both to be present. Flavoproteins are mainly located in the mitochondria because of their redox power. Of all flavoproteins, 90% perform redox reactions and the other 10% are transferases, lyases, isomerases, ligases.

Oxidation of carbon-heteroatom bonds

Carbon-nitrogen

Monoamine oxidase (MAO) is an extensively studied flavoenzyme due to its biological importance with the catabolism of norepinephrine, serotonin and dopamine. MAO oxidizes primary, secondary and tertiary amines, which nonenzymatically hydrolyze from the imine to aldehyde or ketone. Even though this class of enzyme has been extensively studied, its mechanism of action is still being debated. Two mechanisms have been proposed: a radical mechanism and a nucleophilic mechanism. The radical mechanism is less generally accepted because no spectral or electron paramagnetic resonance evidence exists for the presence of a radical intermediate. The nucleophilic mechanism is more favored because it is supported by site-directed mutagenesis studies which mutated two tyrosine residues that were expected to increase the nucleophilicity of the substrates.

Carbon-oxygen

Glucose oxidase (GOX) catalyzes the oxidation of β-D-glucose to D-glucono-δ-lactone with the simultaneous reduction of enzyme-bound flavin. GOX exists as a homodimer, with each subunit binding one FAD molecule. Crystal structures show that FAD binds in a deep pocket of the enzyme near the dimer interface. Studies showed that upon replacement of FAD with 8-hydroxy-5-carba-5-deaza FAD, the stereochemistry of the reaction was determined by reacting with the re face of the flavin. During turnover, the neutral and anionic semiquinones are observed which indicates a radical mechanism.

Carbon-sulfur

Prenylcysteine lyase (PCLase) catalyzes the cleavage of prenylcysteine (a protein modification) to form an isoprenoid aldehyde and the freed cysteine residue on the protein target. The FAD is non-covalently bound to PCLase. Not many mechanistic studies have been done looking at the reactions of the flavin, but the proposed mechanism is shown below. A hydride transfer from the C1 of the prenyl moiety to FAD is proposed, resulting in the reduction of the flavin to FADH2. COformED IS a carbocation that is stabilized by the neighboring sulfur atom. FADH2 then reacts with molecular oxygen to restore the oxidized enzyme.

Carbon-carbon

UDP-N-acetylenolpyruvylglucosamine Reductase (MurB) is an enzyme that catalyzes the NADPH-dependent reduction of enolpyruvyl-UDP-N-acetylglucosamine (substrate) to the corresponding D-lactyl compound UDP-N-acetylmuramic acid (product). MurB is a monomer and contains one FAD molecule. Before the substrate can be converted to product, NADPH must first reduce FAD. Once NADP+ dissociates, the substrate can bind and the reduced flavin can reduce the product.

Thiol/disulfide chemistry

Glutathione reductase (GR) catalyzes the reduction of glutathione disulfide (GSSG) to glutathione (GSH). GR requires FAD and NADPH to facilitate this reaction; first a hydride must be transferred from NADPH to FAD. The reduced flavin can then act as a nucleophile to attack the disulfide, this forms the C4a-cysteine adduct. Elimination of this adduct results in a flavin-thiolate charge-transfer complex.

Electron transfer reactions

Cytochrome P450 type enzymes that catalyze monooxygenase (hydroxylation) reactions are dependent on the transfer of two electrons from FAD to the P450. Two types of P450 systems are found in eukaryotes. The P450 systems that are located in the endoplasmic reticulum are dependent on a cytochrome P-450 reductase (CPR) that contains both an FAD and an FMN. The two electrons on reduced FAD (FADH2) are transferred one at a time to FMN and then a single electron is passed from FMN to the heme of the P450.

The P450 systems that are located in the mitochondria are dependent on two electron transfer proteins: An FAD containing adrenodoxin reductase (AR) and a small iron-sulfur group containing protein named adrenodoxin. FAD is embedded in the FAD-binding domain of AR. The FAD of AR is reduced to FADH2 by transfer of two electrons from NADPH that binds in the NADP-binding domain of AR. The structure of this enzyme is highly conserved to maintain precisely the alignment of electron donor NADPH and acceptor FAD for efficient electron transfer. The two electrons in reduced FAD are transferred one a time to adrenodoxin which in turn donates the single electron to the heme group of the mitochondrial P450.

The structures of the reductase of the microsomal versus reductase of the mitochondrial P450 systems are completely different and show no homology.

Redox

p-Hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase (PHBH) catalyzes the oxygenation of p-hydroxybenzoate (pOHB) to 3,4-dihyroxybenzoate (3,4-diOHB); FAD, NADPH and molecular oxygen are all required for this reaction. NADPH first transfers a hydride equivalent to FAD, creating FADH−, and then NADP+ dissociates from the enzyme. Reduced PHBH then reacts with molecular oxygen to form the flavin-C(4a)-hydroperoxide. The flavin hydroperoxide quickly hydroxylates pOHB, and then eliminates water to regenerate oxidized flavin. An alternative flavin-mediated oxygenation mechanism involves the use of a flavin-N(5)-oxide rather than a flavin-C(4a)-(hydro)peroxide.

Nonredox

Chorismate synthase (CS) catalyzes the last step in the shikimate pathway—the formation of chorismate. Two classes of CS are known, both of which require FMN, but are divided on their need for NADPH as a reducing agent. The proposed mechanism for CS involves radical species. The radical flavin species has not been detected spectroscopically without using a substrate analogue, which suggests that it is short-lived. However, when using a fluorinated substrate, a neutral flavin semiquinone was detected.

Complex flavoenzymes

Glutamate synthase catalyzes the conversion of 2-oxoglutarate into L-glutamate with L-glutamine serving as the nitrogen source for the reaction. All glutamate syntheses are iron-sulfur flavoproteins containing an iron-sulfur cluster and FMN. The three classes of glutamate syntheses are categorized based on their sequences and biochemical properties. Even though there are three classes of this enzyme, it is believed that they all operate through the same mechanism, only differing by what first reduces the FMN. The enzyme produces two glutamate molecules: one by the hydrolysis of glutamine (forming glutamate and ammonia), and the second by the ammonia produced from the first reaction attacking 2-oxoglutarate, which is reduced by FMN to glutamate.

Clinical significance

Due to the importance of flavoproteins, it is unsurprising that approximately 60% of human flavoproteins cause human disease when mutated. In some cases, this is due to a decreased affinity for FAD or FMN and so excess riboflavin intake may lessen disease symptoms, such as for multiple acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. In addition, riboflavin deficiency itself (and the resulting lack of FAD and FMN) can cause health issues. For example, in ALS patients, there are decreased levels of FAD synthesis. Both of these paths can result in a variety of symptoms, including developmental or gastrointestinal abnormalities, faulty fat break-down, anemia, neurological problems, cancer or heart disease, migraine, worsened vision and skin lesions. The pharmaceutical industry therefore produces riboflavin to supplement diet in certain cases. In 2008, the global need for riboflavin was 6,000 tons per year, with production capacity of 10,000 tons. This $150 to 500 million market is not only for medical applications, but is also used as a supplement to animal food in the agricultural industry and as a food colorant.

Drug design

New design of anti-bacterial medications is of continuing importance in scientific research as bacterial antibiotic resistance to common antibiotics increases. A specific metabolic protein that uses FAD (Complex II) is vital for bacterial virulence, and so targeting FAD synthesis or creating FAD analogs could be a useful area of investigation. Already, scientists have determined the two structures FAD usually assumes once bound: either an extended or a butterfly conformation, in which the molecule essentially folds in half, resulting in the stacking of the adenine and isoalloxazine rings. FAD imitators that are able to bind in a similar manner but do not permit protein function could be useful mechanisms of inhibiting bacterial infection. Alternatively, drugs blocking FAD synthesis could achieve the same goal; this is especially intriguing because human and bacterial FAD synthesis relies on very different enzymes, meaning that a drug made to target bacterial FAD synthase would be unlikely to interfere with the human FAD synthase enzymes.

Optogenetics

Optogenetics allows control of biological events in a non-invasive manner. The field has advanced in recent years with a number of new tools, including those to trigger light sensitivity, such as the Blue-Light-Utilizing FAD domains (BLUF). BLUFs encode a 100 to 140 amino acid sequence that was derived from photoreceptors in plants and bacteria. Similar to other photoreceptors, the light causes structural changes in the BLUF domain that results in disruption of downstream interactions. Current research investigates proteins with the appended BLUF domain and how different external factors can impact the proteins.

Treatment monitoring

There are a number of molecules in the body that have native fluorescence including tryptophan, collagen, FAD, NADH and porphyrins. Scientists have taken advantage of this by using them to monitor disease progression or treatment effectiveness or aid in diagnosis. For instance, native fluorescence of a FAD and NADH is varied in normal tissue and oral submucous fibrosis, which is an early sign of invasive oral cancer. Doctors therefore have been employing fluorescence to assist in diagnosis and monitor treatment as opposed to the standard biopsy.

その他の画像

-

FADH2

こちらも参照

外部リンク

- FAD bound to proteins in the PDB

- FAD entry in the NIH Chemical Database