Obesity/ja: Difference between revisions

Created page with "肥満政策アクション(OPA)の枠組みでは、対策を「上流」政策、「中流」政策、「下流」政策に分けている。上流の政策は社会を変えることに関係し、中流の政策は個人レベルで肥満の原因と考えられる行動を変えようとするもので、下流の政策は現在肥満の人を治療するものである。" |

Created page with "いくつかの低カロリー食は効果的である。短期的には、低炭水化物食の方が低脂肪食よりも体重減少に良いと思われる。しかし、長期的には、すべてのタイプの低炭水化物食と低脂肪食が等しく有益であるように見える。さまざまな食事に関連する心臓病と糖尿病のリスクは同程度のようである。肥満者における地中..." Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| (82 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 87: | Line 87: | ||

{{Main/ja|Obesity-associated morbidity/ja}} | {{Main/ja|Obesity-associated morbidity/ja}} | ||

肥満は多くの身体的・精神的疾患のリスクを高める。このような併存疾患は、[[metabolic syndrome/ja|メタボリックシンドローム]]に最もよく見られる: [[diabetes mellitus type 2/ja|2型糖尿病]]、[[hypertension/ja|高血圧]]、[[hypercholesterolemia/ja|高コレステロール血症]]、[[hypertriglyceridemia/ja|高トリグリセリド血症]]が含まれる。[[:en:RAK Hospital|RAK病院]]の研究によれば、肥満の人は[[long COVID/ja|長いCOVID]]を発症するリスクが高い。CDCは、肥満がCOVID-19の重症化に対する唯一最強の危険因子であることを明らかにした。 | |||

合併症は、肥満が直接の原因であるか、あるいは食生活の乱れや[[sedentary lifestyle/ja|座りがちな生活習慣]]など共通の原因を持つメカニズムを通じて間接的に関連している。肥満と特定の疾患との関連性の強さは様々である。最も強いもののひとつは[[type 2 diabetes/ja|2型糖尿病]]との関連である。過剰な体脂肪は、男性では糖尿病の症例の64%、女性では77%を引き起こしている。 | |||

健康への影響は大きく2つのカテゴリーに分類される:脂肪量の増加の影響に起因するもの([[osteoarthritis/ja|変形性関節症]]、[[obstructive sleep apnea/ja|閉塞性睡眠時無呼吸症候群]]、社会的汚名など)と[[fat cells/ja|脂肪細胞]]の増加によるもの([[diabetes mellitus/ja|糖尿病]]、[[cancer/ja|がん]]、[[cardiovascular disease/ja|心血管系疾患]]、[[non-alcoholic fatty liver disease/ja|非アルコール性脂肪肝疾患]])。体脂肪の増加はインスリンに対する身体の反応を変化させ、潜在的に[[insulin resistance/ja|インスリン抵抗性]]を引き起こす。脂肪の増加はまた、[[inflammation/ja|炎症性状態]]や[[thrombosis/ja|血栓性状態]]を引き起こす。 | |||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

|- | |- | ||

! | ! 医療分野 | ||

! | ! 状態 | ||

! | ! 医療分野 | ||

! | ! 状態 | ||

|- | |- | ||

| width="10%" | [[Cardiology]] | | width="10%" | [[Cardiology/ja]] | ||

| | | | ||

* [[Coronary heart disease]] | * [[Coronary heart disease/ja|冠状動脈性心臓病]]: [[angina pectoris/ja|狭心症]]や[[myocardial infarction/ja|心筋梗塞]] | ||

* [[Congestive heart failure]] | * [[Congestive heart failure/ja|うっ血性心不全]] | ||

* [[High blood pressure]] | * [[High blood pressure/ja|高血圧]] | ||

* [[Dyslipidemia| | * [[Dyslipidemia/ja|コレステロール値の異常]] | ||

* [[Deep vein thrombosis]] | * [[Deep vein thrombosis/ja|深部静脈血栓症]]と[[pulmonary embolism/ja|肺塞栓症]] | ||

| [[Dermatology]] | | [[Dermatology/ja]] | ||

| | | | ||

* [[Acanthosis nigricans]] | * [[Acanthosis nigricans/ja]] | ||

* [[Lymphedema]] | * [[Lymphedema/ja]] | ||

* [[Cellulitis]] | * [[Cellulitis/ja]] | ||

* [[Hirsutism]] | * [[Hirsutism/ja]] | ||

* [[Intertrigo]] | * [[Intertrigo/ja]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[Endocrinology]] | | [[Endocrinology/ja]]と[[reproductive medicine/ja]] | ||

| | | | ||

* [[Diabetes mellitus]] | * [[Diabetes mellitus/ja]] | ||

* [[Polycystic ovarian syndrome]] | * [[Polycystic ovarian syndrome/ja]] | ||

* [[menstruation| | * [[menstruation/ja|生理]]障害 | ||

* [[Infertility]] | * [[Infertility/ja]] | ||

* [[Maternal obesity| | * [[Maternal obesity/ja|妊娠中の合併症]] | ||

* [[Birth defects]] | * [[Birth defects/ja]] | ||

* [[Stillbirth| | * [[Stillbirth/ja|子宮内胎児死亡]] | ||

| <!--Alphabetized-->[[Gastroenterology]] | | <!--Alphabetized-->[[Gastroenterology/ja]] | ||

| | | | ||

* [[Gastroesophageal reflux disease]] | * [[Gastroesophageal reflux disease/ja]] | ||

* [[Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease| | * [[Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease/ja|脂肪肝]] | ||

* [[Cholelithiasis]] ( | * [[Cholelithiasis/ja]] (胆石) | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[Neurology]] | | [[Neurology/ja]] | ||

| style="width:40%;" | | | style="width:40%;" | | ||

* [[Stroke]] | * [[Stroke/ja]] | ||

* [[Meralgia paresthetica]] | * [[Meralgia paresthetica/ja]] | ||

* [[Migraines]] | * [[Migraines/ja]] | ||

* [[Carpal tunnel syndrome]] | * [[Carpal tunnel syndrome/ja]] | ||

* [[Dementia]] | * [[Dementia/ja]] | ||

* [[Idiopathic intracranial hypertension]] | * [[Idiopathic intracranial hypertension/ja]] | ||

* [[Multiple sclerosis]] | * [[Multiple sclerosis/ja]] | ||

| [[Oncology]] | | [[Oncology/ja]] | ||

| | | | ||

* [[esophageal cancer| | * [[esophageal cancer/ja|食道]] | ||

* [[colorectal cancer| | * [[colorectal cancer/ja|大腸]] | ||

* [[pancreatic cancer| | * [[pancreatic cancer/ja|膵臓]] | ||

* [[Gallbladder cancer| | * [[Gallbladder cancer/ja|胆嚢]] | ||

* [[Endometrial cancer| | * [[Endometrial cancer/ja|子宮内膜]] | ||

* [[Renal cell carcinoma| | * [[Renal cell carcinoma/ja|腎臓]] | ||

* [[Leukemia]] | * [[Leukemia/ja]] | ||

* [[Hepatocellular carcinoma]] | * [[Hepatocellular carcinoma/ja]] | ||

* [[Malignant melanoma]] | * [[Malignant melanoma/ja]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| style="width:10%;" |[[Psychiatry]] | | style="width:10%;" |[[Psychiatry/ja]] | ||

| style="width:40%;" | | | style="width:40%;" | | ||

* [[Major depressive disorder| | * 女性における[[Major depressive disorder/ja|うつ病]] | ||

* | * 社会的[[Social stigma/ja|スティグマティゼーション]] | ||

| [[Respirology]] | | [[Respirology/ja]] | ||

| | | | ||

* [[Sleep apnea| | * [[Sleep apnea/ja|閉塞性睡眠時無呼吸症候群]] | ||

* [[Obesity hypoventilation syndrome]] | * [[Obesity hypoventilation syndrome/ja]] | ||

* [[Asthma]] | * [[Asthma/ja]] | ||

* | * [[general anaesthesia/ja|全身麻酔]]中の合併症の増加 | ||

* | * 重症COVID-19のリスクが高まる | ||

|- | |- | ||

| [[Rheumatology]] | | [[Rheumatology/ja]]と[[orthopedics/ja]] | ||

| | | | ||

* [[Gout]] | * [[Gout/ja]] | ||

* | * 運動能力が低い | ||

* [[Osteoarthritis]] | * [[Osteoarthritis/ja]] | ||

* [[Low back pain]] | * [[Low back pain/ja]] | ||

| [[Urology]] | | [[Urology/ja]]と[[Nephrology/ja]] | ||

| | | | ||

* [[Erectile dysfunction]] | * [[Erectile dysfunction/ja]] | ||

* [[Urinary incontinence]] | * [[Urinary incontinence/ja]] | ||

* [[Chronic renal failure]] | * [[Chronic renal failure/ja]] | ||

* [[Hypogonadism]] | * [[Hypogonadism/ja]] | ||

* [[Buried penis]] | * [[Buried penis/ja]] | ||

|} | |} | ||

==== 健康の指標 ==== | |||

==== | {{Main/ja|Metabolically healthy obesity/ja}} | ||

{{Main|Metabolically healthy obesity}} | |||

新しい研究では、臨床医がより健康的な肥満者を特定する方法と、肥満者を一枚岩として扱わない方法に焦点が当てられている。肥満による医学的合併症を経験しない肥満者を''[[metabolically healthy obese/ja|(代謝的に)健康な肥満]]''と呼ぶことがあるが、このグループが(特に高齢者において)どの程度存在するかについては論争がある。''メタボ健常者''とみなされる人の数は、使用される定義によって異なり、普遍的に受け入れられる定義はない。代謝異常が比較的少ない肥満者も多数存在し、医学的合併症のない肥満者も少数派である。[[:en:American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists|米国臨床内分泌学会]]のガイドラインでは、2型糖尿病発症リスクの評価方法を検討する際に、肥満患者に対して[[risk stratification/ja|リスク層別化]]を行うよう医師に呼びかけている。 | |||

2014年、BioSHaRE-[[:en:European Union|EU]]([[:en:Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre|マギル大学保健センター研究所]]傘下のチームであるMaelstrom Researchがスポンサー)は、''健康的肥満''の定義を2つに分けた: | |||

{| class="wikitable" style="background-color:rgba(0,0,0,0);border:none" | {| class="wikitable" style="background-color:rgba(0,0,0,0);border:none" | ||

|+BioSHaRE | |+BioSHaRE 健康な肥満(HOP)プロジェクト基準(2014年)<br />{{Nobold|患者は、[[body mass index/ja|肥満度]]が30以上であり、以下のすべてを満たしていなければならない:}} | ||

|style="border:0px"| | |style="border:0px"| | ||

! | !厳格でない | ||

! | !より厳格に | ||

|- | |- | ||

! colspan="3" |[[Blood pressure]] | ! colspan="3" |[[Blood pressure/ja|血圧]]は、医薬品の助けを借りずに次のように測定した。 | ||

|- | |- | ||

! | !全体 ([[:en:mmHg|mmHg]]) | ||

|≤ 140 | |≤ 140 | ||

|≤ 130 | |≤ 130 | ||

|- | |- | ||

![[Systolic]] (mmHg) | ![[Systolic/ja]] (mmHg) | ||

|<small>N/A</small> | |<small>N/A</small> | ||

|≤ 85 | |≤ 85 | ||

|- | |- | ||

![[Diastolic]] (mmHg) | ![[Diastolic/ja]] (mmHg) | ||

|≤ 90 | |≤ 90 | ||

|<small>N/A</small> | |<small>N/A</small> | ||

|- | |- | ||

! colspan="3" |[[Blood sugar level]] | ! colspan="3" |[[Blood sugar level/ja|血糖値]]は、医薬品の助けを借りずに次のように測定した。 | ||

|- | |- | ||

! | !血糖値 ([[:en:mmol|mmol]]/[[:en:Litre|L]]) | ||

|≤ 7.0 | |≤ 7.0 | ||

|≤ 6.1 | |≤ 6.1 | ||

|- | |- | ||

! colspan="3" |[[Triglycerides]] | ! colspan="3" |[[Triglycerides/ja|トリグリセリド]]は、医薬品の助けを借りることなく、次のようにして測定した。 | ||

|- | |- | ||

! | !空腹時 (mmol/L) | ||

| colspan="2" |≤ 1.7 | | colspan="2" |≤ 1.7 | ||

|- | |- | ||

! | !非空腹時 (mmol/L) | ||

| colspan="2" |≤ 2.1 | | colspan="2" |≤ 2.1 | ||

|- | |- | ||

! colspan="3" |[[High-density lipoprotein]] | ! colspan="3" |[[High-density lipoprotein/ja|高比重リポ蛋白]]は、医薬品の助けを借りずに以下のように測定した。 | ||

|- | |- | ||

! | !男性 (mmol/L) | ||

| colspan="2" |> 1.03 | | colspan="2" |> 1.03 | ||

|- | |- | ||

! | !女性 (mmol/L) | ||

| colspan="2" |> 1.3 | | colspan="2" |> 1.3 | ||

|- | |- | ||

! colspan="3" | | ! colspan="3" |いかなる[[cardiovascular disease/ja|心血管系疾患]]の診断も受けていない。 | ||

|} | |} | ||

BioSHaREは、この基準を設定するために、年齢とタバコの使用をコントロールし、両者が肥満に伴うメタボリックシンドロームにどのような影響を及ぼすかを研究した。メタボ健常肥満の定義には、BMIではなくウエスト周囲径に基づくものなど、他の定義も存在するが、これは特定の個人においては信頼性に欠ける。 | |||

肥満者における健康のもう一つの識別指標は[[Triceps surae muscle/ja|カフ]][[Muscle strength/ja|筋力]]であり、これは肥満者の[[physical fitness/ja|体力]]と正の相関がある。一般的に[[body composition/ja|身体組成]]は、代謝的に健康な肥満の存在を説明するのに役立つという仮説がある-代謝的に健康な肥満者は、[[metabolic syndrome/ja|メタボリックシンドローム]]の肥満者と同等の全体的な脂肪量を有するにもかかわらず、[[Ectopia (medicine)/ja|異所性]]脂肪(脂肪組織以外の組織に蓄積された脂肪)の量が少ないことがしばしば発見される。 | |||

===生存のパラドックス=== | |||

{{See also/ja|Obesity paradox/ja}} | |||

{{See also|Obesity paradox}} | 一般集団における肥満の健康への悪影響は、利用可能な研究エビデンスによって十分に裏付けられているが、特定のサブグループにおける健康転帰は、BMIが上昇すると改善するようであり、これは肥満生存パラドックスとして知られる現象である。このパラドックスは、1999年に[[hemodialysis/ja|血液透析]]を受けている過体重および肥満の人々において初めて報告され、その後、[[heart failure/ja|心不全]]および[[Peripheral vascular disease/ja|末梢動脈疾患]](PAD)を有する人々においても見出されている。 | ||

心不全患者では、BMIが30.0から34.9の人は標準体重の人より死亡率が低かった。これは、病気が進行するにつれて体重が減少することが多いためと考えられている。他の心臓病でも同様の結果が得られている。クラスIの肥満で心臓病を持つ人は、心臓病を持つ標準体重の人よりも、さらなる心臓病の発生率は高くない。しかし、肥満の程度が高い人では、さらなる心血管イベントのリスクが増加する。[[Coronary artery bypass surgery/ja|心臓バイパス手術]]後でも、過体重や肥満では死亡率の増加はみられない。ある研究では、生存率の向上は、肥満の人が心臓イベント後に受ける治療がより積極的であることによって説明できるとしている。別の研究では、PAD患者の[[chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/ja|慢性閉塞性肺疾患]](COPD)を考慮すると、肥満の利点はもはや存在しないことがわかった。 | |||

==原因== | |||

{{Anchor|Causes}} | |||

肥満の「[[a calorie is a calorie/ja|a calorie is a calorie]]」モデルは、ほとんどの肥満の原因として、過剰な[[food energy/ja|食物エネルギー]]摂取と[[physical activity/ja|身体活動]]不足の組み合わせを仮定している。遺伝、医学的理由、精神疾患によるものは限られている。対照的に、社会レベルでの肥満率の増加は、簡単に手に入り、口にしやすい食事、増加した[[:en:Effects of the car on societies|自動車への依存]]、機械化された製造業によるものと考えられている。 | |||

世界的な肥満率上昇の原因として、[[sleep debt/ja|睡眠不足]]、[[endocrine disruptor/ja|内分泌攪乱物質]]、特定の薬物([[atypical antipsychotics/ja|非定型抗精神病薬]]など)の使用量の増加、周囲温度の上昇、人口動態の変化、初産婦の年齢上昇、[[tobacco smoking/ja|タバコ]]喫煙率の低下、人口統計学的変化、初産婦の年齢上昇、環境からの[[epigenetic/ja|エピジェネティック]]な調節異常の変化、[[assortative mating/ja|同系交配]]による表現型変異の増加、[[dieting/ja|ダイエット]]に対する社会的圧力などである。ある研究によると、これらのような要因は、過剰な食物エネルギー摂取や運動不足と同じくらい大きな役割を果たしている可能性がある。しかし、肥満の原因として提案されているものの影響の相対的な大きさは様々であり、確定的な見解を出すにはヒトを対象としたランダム化比較試験が必要であるため、不確かである。 | |||

[[:en:Endocrine Society|内分泌学会]]によれば、「肥満は、単に過剰な体重の受動的蓄積から生じるのではなく、[[energy homeostasis/ja|エネルギー恒常性]]システムの障害であることを示唆する証拠が増えている」という。 | |||

===食事=== | |||

{{Main|Diet and obesity}} | {{Main|Diet and obesity}} | ||

<div class="thumb tright" style="width: 417px; "> | <div class="thumb tright" style="width: 417px; "> | ||

<div class="thumbinner" > | <div class="thumbinner" > | ||

<div style="float: left; margin: 1px; width: 202px"> | <div style="float: left; margin: 1px; width: 202px"> | ||

<div class="thumbimage">[[File:World map of calory consumption 1961 (v2).svg|200px|alt= | <div class="thumbimage">[[File:World map of calory consumption 1961 (v2).svg|200px|alt=(左)1961年における国民の食料エネルギー消費量を反映するように、各国を色分けした世界地図。北米、ヨーロッパ、オーストラリアは比較的摂取量が多いが、アフリカとアジアはかなり少ない。]] | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="thumbcaption" style="clear:left">1961 | <div class="thumbcaption" style="clear:left">1961 | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

</div><div style="float: left; margin: 1px; width: 202px"> | </div><div style="float: left; margin: 1px; width: 202px"> | ||

<div class="thumbimage">[[File:World map of Energy consumption 2001-2003.svg|200px|alt= | <div class="thumbimage">[[File:World map of Energy consumption 2001-2003.svg|200px|alt=(右)2001年から2003年の食料エネルギー消費量を反映するように、各国を色分けした世界地図。北米、ヨーロッパ、オーストラリアの消費量は、1971年の以前の水準に比べて増加している。アジアの多くの地域でも食料消費は大幅に増加している。しかし、アフリカの食糧消費量は依然として低い。]] | ||

</div><div class="thumbcaption" style="clear:left">2001–03 | </div><div class="thumbcaption" style="clear:left">2001–03 | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

</div><div class="thumbcaption" style="clear: left; text-align: left; background: transparent"> | </div><div class="thumbcaption" style="clear: left; text-align: left; background: transparent">1961年(左)と2001-2003年(右)の1人1日当たりの食事エネルギー利用可能量マップ 1人1日当たりのカロリー(1人1日当たりキロジュール) | ||

{{Col-begin}} | {{Col-begin}} | ||

{{Col-break}} | {{Col-break}} | ||

| Line 306: | Line 280: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

[[File:World Per Person Energy Consumption.png|thumb|upright=1.6|alt= | [[File:World Per Person Energy Consumption.png|thumb|upright=1.6|alt=1961年から2002年にかけての、世界の1人1日当たりの食料エネルギー消費量の漸増を示すグラフ。|1961年から2002年までの世界の一人当たり平均エネルギー消費量]] | ||

口当たりのよい高カロリー食品(特に脂肪、砂糖、特定の動物性タンパク質)に対する過剰な食欲は、世界的な肥満を引き起こす主な要因と考えられているが、これはおそらく、食べたいという衝動に影響する神経伝達物質のバランスが崩れているためであろう。一人当たりの[[食事エネルギー供給量]]は、地域や国によって著しく異なる。また、時代とともに大きく変化している。1970年代初頭から1990年代後半にかけて、東欧を除く世界のすべての地域で、1人1日あたりに利用可能な平均[[food energy/ja|食物エネルギー]](買物量)は増加した。1996年には、米国が一人当たり{{convert|3654|Cal}}で最も利用可能量が多かった。2003年にはさらに増加し、{{convert|3754|Cal}}となった。1990年代後半には、ヨーロッパ人は1人当たり{{convert|3394|Cal}}、アジアの発展途上地域では1人当たり{{convert|2648|Cal}}、サハラ以南のアフリカでは1人当たり{{convert|2176|Cal}}であった。食品の総エネルギー消費量は肥満と関係があることがわかっている。 | |||

[[File:Prevalence Of Obesity In The Adult Population By Region.svg|thumb|地域別成人人口における肥満の有病率(2000年~2016年)|330x330px]] | |||

[[:en:Dietary Guidelines for Americans|食事ガイドライン]]が普及しても、過食や食生活の選択ミスの問題に対処することはほとんどできなかった。1971年から2000年にかけて、米国の肥満率は14.5%から30.9%に増加した。同じ期間に、食品の平均消費エネルギー量も増加している。女性の平均増加量は1日あたり{{convert|335|Cal}}(1971年では{{convert|1542|Cal}}、2004年では{{convert|1877|Cal}})であり、男性の平均増加量は1日あたり{{convert|168|Cal}}(1971年では{{convert|2450|Cal}}、2004年では{{convert|2618|Cal}})であった。この余分な食物エネルギーのほとんどは、脂肪消費よりもむしろ炭水化物消費の増加によるものである。これらの余分な炭水化物の主な供給源は、アメリカの若年成人の1日の食物エネルギーのほぼ25%を占めるようになった甘味飲料と、ポテトチップスである。清涼飲料水、果実飲料、アイスティーなどの[[sweetened beverages/ja|甘味飲料]]の消費は、肥満率の上昇、メタボリックシンドロームや2型糖尿病のリスクの上昇に寄与していると考えられている。[[Vitamin D deficiency/ja|ビタミンD欠乏症]]は肥満に関連する疾患と関連している。 | |||

社会が[[food energy/ja|エネルギー密度が高い]]、大盛り、[[Fast food/ja|ファーストフード]]の食事にますます依存するようになるにつれて、ファストフードの消費と肥満の関連性がより懸念されるようになる。米国では、1977年から1995年の間に、ファストフードの消費量は3倍になり、これらの食事からの食物エネルギー摂取量は4倍になった。 | |||

アメリカやヨーロッパにおける[[:en:Agricultural policy|農業政策]]や[[:en:Green Revolution (agriculture)|技術]]は、[[food prices/ja|食料価格]]の低下をもたらした。アメリカでは[[:en:U.S. farm bill|農業法案]]によるトウモロコシ、大豆、小麦、米への補助金によって、加工食品の主な供給源は果物や野菜に比べて安価になった。[[Calorie count laws/ja|カロリー計算法]]や[[nutrition facts label/ja|栄養成分表示]]は、食品のエネルギーがどれだけ消費されているかを意識するなど、より健康的な食品を選択するよう人々を誘導しようとするものである。 | |||

肥満の人は、標準体重の人に比べて、常に自分の食事消費量を過少に報告する。これは、[[:en:calorimeter|熱量計]]室内で行われた人体実験と直接観察の両方によって裏付けられている。 | |||

[[ | |||

===座りっぱなしのライフスタイル=== | |||

{{See also/ja|Sedentary lifestyle/ja|Exercise trends/ja}} | |||

座りがちなライフスタイルは、肥満に大きな役割を果たしている可能性がある。世界的に、身体的負荷の少ない仕事へのシフトが大きく進んでおり、現在、世界人口の少なくとも30%が運動不足である。この主な原因は、機械化された交通手段の増加や、家庭内での省力化技術の普及である。子どもたちにおいては、身体活動レベルの低下(特に歩行量と体育の減少が著しい)が見られるが、これは安全への懸念、社会的相互作用の変化(近所の子どもたちとの関係が希薄になるなど)、不適切な都市設計(安全な身体活動のための公共スペースが少なすぎるなど)が原因であると考えられる。活動的な余暇[[physical activity/ja|身体活動]]における世界の傾向は、あまり明確ではない。世界保健機関(WHO)は、世界中の人々があまり活動的でないレクリエーションに興じていることを示しているが、フィンランドの調査では増加しており、米国の調査では余暇の身体活動に大きな変化はないとしている。子どもの身体活動は、重要な要因ではないかもしれない。 | |||

子どもも大人も、テレビ視聴時間と肥満リスクには関連がある。メディアへの露出が増えると小児肥満の割合が増加し、その割合はテレビ視聴時間に比例して増加する。 | |||

===遺伝学=== | |||

{{Main/ja|Genetics of obesity/ja}} | |||

[[File:La monstrua desnuda (1680), de Juan Carreño de Miranda..jpg|thumb|upright=1.3|alt=黒髪のピンク色の頬の肥満した若い女性のヌードがテーブルにもたれている絵。彼女は左手に葡萄と葡萄の葉を持ち、性器を覆っている。|1680年に[[:en:Juan Carreno de Miranda|フアン・カレーニョ・デ・ミランダ]]によって描かれた、[[Prader–Willi syndrome/ja|プラダー・ウィリー症候群]]と推定される少女の絵「La Monstrua Desnuda(裸の怪物)」である。]] | |||

他の多くの病状と同様に、肥満は遺伝的要因と環境的要因の相互作用の結果である。[[appetite/ja|食欲]]や[[metabolism/ja|代謝]]を制御する様々な[[gene/ja|遺伝子]]の[[Polymorphism (biology)/ja多型]]は、十分な食物エネルギーが存在する場合に肥満の素因となる。2006年の時点で、ヒトゲノム上のこれらの部位のうち41以上が、好ましい環境が存在する場合に肥満の発症に関連するとされている。[[FTO gene/ja|FTO遺伝子]](脂肪量および肥満関連遺伝子)を2コピー持つ人は、リスク[[allele/ja|対立遺伝子]]を持たない人に比べて、平均で体重が3-4 kg多く、肥満のリスクが1.67倍高いことが判明している。[[heritability/ja|遺伝による]]BMIの差は、調査した集団によって6%から85%まで様々である。 | |||

肥満は、[[Prader–Willi syndrome/ja|プラダー・ウィリー症候群]]、[[Bardet–Biedl syndrome/ja|バルデ・ビードル症候群]]、[[Cohen syndrome/ja|コーエン症候群]]、[[MOMO syndrome/ja|MOMO症候群]]などのいくつかの症候群における主要な特徴である(これらの疾患を除外するために「非症候群性肥満」という用語が使われることがある)。早期発症の高度肥満(10歳以前に発症し、体格指数が正常値より[[:en:standard deviation|標準偏差]]3以上高いことで定義される)では、7%が1点のDNA変異を保有している。 | |||

[[ | |||

特定の遺伝子ではなく、遺伝パターンに注目した研究によると、2人の[[parental obesity/ja|肥満の親]]の子供の80%が肥満であったのに対し、標準体重の2人の親の子供は10%未満であった。同じ環境にさらされても、基礎にある遺伝によって肥満のリスクは異なる。 | |||

[[thrifty gene hypothesis/ja|倹約遺伝子仮説]]は、人類が進化する過程で食事が乏しくなったために肥満になりやすくなったと仮定している。脂肪としてエネルギーを蓄えることで稀にある豊かな時期を利用する能力は、食料の入手可能性が変化する時期に有利であり、脂肪を多く蓄えた個体は[[famine/ja|飢饉]]を生き延びる可能性が高くなる。しかし、脂肪を蓄えるこの傾向は、食糧供給が安定している社会では不適応となる。この説は様々な批判を受けており、[[drifty gene hypothesis/ja|漂流遺伝子仮説]]や[[thrifty phenotype/ja|倹約的表現型仮説]]といった進化論に基づく他の説も提唱されている。 | |||

===その他の病気=== | |||

特定の身体的・精神的疾患およびその治療に用いられる医薬品は、肥満のリスクを高める可能性がある。肥満リスクを増加させる医学的疾患には、先天性または後天性の疾患だけでなく、いくつかのまれな遺伝的症候群(上記)が含まれる: | |||

[[hypothyroidism/ja|甲状腺機能低下症]]、[[Cushing's syndrome/ja|クッシング症候群]]、[[growth hormone deficiency/ja|成長ホルモン欠乏症]]、および[[binge eating disorder/ja|むちゃ食い障害]]や[[night eating syndrome/ja|夜食症候群]]などのいくつかの[[eating disorder/ja|摂食障害]]がある。しかし、肥満は精神疾患とはみなされていないため、[[Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders/ja|DSM-IVR]]には精神疾患として記載されていない。過体重や肥満のリスクは、精神疾患のある患者では精神疾患のない患者よりも高い。肥満と[[Depression (mood)/ja|うつ病]]は相互に影響し合い、肥満は臨床的うつ病のリスクを高め、またうつ病は肥満を発症する可能性を高める。 | |||

=== 薬物誘発性肥満=== | |||

特定の薬剤が体重増加または[[body composition/ja|体組成]]の変化を引き起こすことがある; これらには、[[insulin/ja|インスリン]]、[[sulfonylurea/ja|スルホニルウレア]]、[[thiazolidinedione/ja|チアゾリジンジオン]]、[[atypical antipsychotic/ja|非定型抗精神病薬]]、[[antidepressant/ja|抗うつ薬]]、[[glucocorticoids/ja|ステロイド]]、特定の[[anticonvulsant/ja|抗けいれん薬]]([[phenytoin/ja|フェニトイン]]および[[valproate/ja|バルプロ酸塩]])、[[pizotifen/ja|ピゾチフェン]]、およびいくつかの形態の[[hormonal contraception/ja|ホルモン避妊薬]]が含まれる。 | |||

===社会的決定要因=== | |||

=== | {{Main/ja|Social determinants of obesity/ja}} | ||

[[File:Yamai no Soshi - Obesity.JPG|thumb|upright=1.3|病気絵巻(「山井の草紙」、12世紀後半)には、金持ちの病気とされる肥満症の金貸しの女性が描かれている。]] | |||

[[File:More adults are obese in more unequal rich countries (cropped).jpg|thumb|upright=1.3|先進国における肥満は、[[:en:economic inequality|経済格差]]と相関関係がある。]] | |||

遺伝的な影響は肥満を理解する上で重要ではあるが、特定の国や世界的に見られる劇的な増加を完全に説明することはできない。エネルギー消費量がエネルギー消費量を上回ると、個人単位では体重が増加することは認められているが、社会規模でのこの2つの要因の変化の原因については、多くの議論がある。原因については諸説あるが、様々な要因が絡み合っているとする説が多い。 | |||

[[:en:social class|社会階級]]とBMIの相関関係は世界的に異なる。1989年の調査では、先進国では社会階層の高い女性は肥満になりにくいことがわかった。異なる社会階層の男性の間では、有意な差は見られなかった。発展途上国では、社会階層の高い女性、男性、子どもの肥満率が高かった。2007年にも同じ研究が繰り返され、同じような関係が見られたが、より弱いものであった。相関関係の強さの低下は、[[:en:globalization|グローバリゼーション]]の影響によるものと考えられた。先進国では、成人の肥満度や10代の子どもの肥満率は、[[:en:economic inequality|所得格差]]と相関している。同じような関係はアメリカの各州でも見られ、より不平等な州では、より高い社会階層であっても、より多くの成人が肥満である。 | |||

BMIと社会階層との関連については、多くの説明がなされている。先進国では、富裕層はより栄養価の高い食品を買う余裕があり、スリムであることを求める社会的プレッシャーが大きく、[[physical fitness/ja|体力]]に対する期待が大きく、より多くの機会があると考えられている。[[:en:undeveloped countries|未開発国]]では、食料を買う余裕があること、肉体労働によるエネルギー消費が大きいこと、より大きな体格を好む文化的価値観が、観察されたパターンに寄与していると考えられている。身近な人が持つ体重に対する態度も肥満に関与している可能性がある。BMIの経時的変化には、友人、兄弟姉妹、配偶者の間に相関関係がみられる。ストレスや社会的地位の低さは肥満のリスクを高めるようである。 | |||

喫煙は個人の体重に大きな影響を与える。禁煙した人は、10年間で男性で平均4.4kg、女性で平均5.0kg体重が増加する。しかし、喫煙率の変化は肥満率全体にはほとんど影響を及ぼしていない。 | |||

米国では、子供の数が肥満リスクと関係している。女性のリスクは子供1人につき7%増加し、男性のリスクは子供1人につき4%増加する。これは、扶養義務のある子供がいると、欧米の親の身体活動が低下するという事実からも説明できる。 | |||

発展途上国では、都市化が肥満率の増加に一役買っている。中国では、全体的な肥満率は5%以下だが、一部の都市では肥満率が20%を超えている。その一因として、都市設計の問題(身体活動のための公共スペースが不十分など)が考えられる。自転車や徒歩などの[[:en:active transportation|能動的な交通手段]]とは対照的に、自動車で過ごす時間は肥満リスクの増加と相関している。 | |||

幼少期の[[Malnutrition/ja|栄養失調]]は、[[:en:developing world|発展途上国]]における肥満率の上昇に一役買っていると考えられている。栄養不良の期間に起こる内分泌の変化は、より多くの食物エネルギーが利用できるようになると、脂肪の蓄積を促進する可能性がある。 | |||

===腸内細菌=== | |||

[[ | {{See also/ja|Infectobesity/ja}} | ||

感染因子が代謝に及ぼす影響に関する研究は、まだ初期段階にある。[[Gut flora/ja|腸内細菌叢]]は、痩せた人と肥満の人では異なることが示されている。腸内細菌叢が代謝能に影響を及ぼす可能性が示唆されている。この明らかな変化は、肥満の一因となるエネルギーの収穫能力を高めると考えられている。このような違いが肥満の直接的な原因なのか、それとも結果なのかは、まだ明確に決定されていない。小児における[[antibiotics/ja|抗生物質]]の使用も、その後の肥満と関連している。 | |||

[[viruses/ja|ウイルス]]と肥満との関連は、ヒトやいくつかの異なる動物種で発見されている。これらの関連性が肥満率の上昇にどれだけ寄与しているかは、まだ明らかにされていない。 | |||

=== その他の要因 === | |||

睡眠不足は[[sleep and weight/ja|肥満と関連している]]。一方が他方を引き起こすかどうかは不明である。短時間睡眠が体重増加を増加させるとしても、それが意味のある程度なのか、睡眠時間を増やすことが有益なのかは不明である。 | |||

肥満には「[[obesogens/ja|オベソゲン]]」と呼ばれる化学物質が関与しているという説もある。 | |||

[[:en:personality|性格]]のある側面は肥満であることと関連している。[[:en:Loneliness|孤独感]]、[[neuroticism/ja|神経症]]、[[:en:impulsivity|衝動性]]、報酬に対する感受性は肥満の人に多く、[[:en:conscientiousness|良心性]]と[[:en:self-control|自制心]]は肥満の人に少ない。このテーマに関する研究のほとんどは質問紙ベースであるため、これらの結果が性格と肥満の関係を過大評価している可能性がある:肥満の人は[[:en:social stigma of obesity|肥満の社会的スティグマ]]を意識している可能性があり、それに応じて質問紙回答が偏っている可能性がある。同様に、子供の頃に肥満であった人の性格は、肥満の危険因子として働くというよりも、むしろ肥満のスティグマに影響されているかもしれない。 | |||

グローバリゼーションとの関連では、貿易自由化が肥満と関連していることが知られている。1975年から2016年の175カ国のデータに基づく調査では、肥満の有病率は貿易開放度と正の相関があり、その相関は発展途上国でより強いことが示された。 | |||

==病態生理学== | |||

{{Anchor|Pathophysiology}} | |||

{{Main/ja|Pathophysiology of obesity/ja}} | |||

[[File:Fatmouse.jpg|thumb|upright=1.3|alt=同じような大きさの耳、黒い目、ピンク色の鼻を持つ2匹の白いマウス。左のマウスの体の幅は右のマウスの約3倍である。[[leptin/ja|レプチン]]を産生できないために肥満になるマウス(左)と正常なマウス(右)の比較]] | |||

肥満の発症には、持続的な正のエネルギーバランス(エネルギー摂取量がエネルギー消費量を上回る)と、増加した体重の「セットポイント」のリセットという、2つの異なるが関連したプロセスが関与していると考えられている。2つ目のプロセスは、有効な肥満治療法の発見が困難であった理由を説明するものである。このプロセスの根底にある生物学的メカニズムはまだ不明であるが、研究によってそのメカニズムが解明されつつある。 | |||

生物学的レベルでは、肥満の発症と維持には多くの[[pathophysiology/ja|病態生理学]]メカニズムが関与している可能性がある。この研究分野は、1994年にJ.M.フリードマンの研究室によって[[leptin/ja|レプチン]]遺伝子が発見されるまで、ほとんど手がつけられていなかった。レプチンと[[ghrelin/ja|グレリン]]は末梢で産生されるが、[[central nervous system/ja|中枢神経系]]への作用を通して食欲をコントロールしている。特に、これらのホルモンや他の食欲関連ホルモンは、脳の[[hypothalamus/ja|視床下部]]という食物摂取とエネルギー消費の調節の中心的な部位に作用する。視床下部には、食欲を統合する役割に寄与するいくつかの回路があるが、[[melanocortin/ja|メラノコルチン]]経路が最もよく理解されている。この回路は、脳の摂食中枢である[[lateral hypothalamus/ja|外側視床下部]](LH)と満腹中枢である[[ventromedial hypothalamus/ja|視床下部]](VMH)への出力を持つ視床下部の領域、[[arcuate nucleus/ja|弧状核]]から始まる。 | |||

弧状核には2つの異なる[[neuron/ja|ニューロン]]群が存在する。第一のグループは[[neuropeptide Y/ja|神経ペプチドY]](NPY)と[[agouti-related peptide/ja|アグーチ関連ペプチド]](AgRP)を共発現し、LHへの刺激性入力とVMHへの抑制性入力を持つ。第二のグループは[[pro-opiomelanocortin/ja|プロオピオメラノコルチン]](POMC)と[[cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript/ja|コカイン・アンフェタミン制御転写物]](CART)を共発現し、VMHへの刺激入力とLHへの抑制入力を持つ。その結果、NPY/AgRPニューロンは摂食を刺激し満腹感を抑制し、POMC/CARTニューロンは満腹感を刺激し摂食を抑制する。弧状核ニューロンの両グループは、レプチンによって部分的に制御されている。レプチンはNPY/AgRP群を抑制する一方、POMC/CART群を刺激する。したがって、レプチン欠乏症またはレプチン抵抗性のいずれかを介したレプチンシグナル伝達の欠乏は、摂食過多を引き起こし、遺伝性肥満や後天性肥満の一部を説明する可能性がある。 | |||

==管理== | |||

{{Anchor|Management}} | |||

{{Main/ja|Management of obesity/ja}} | |||

肥満の主な治療は、処方された[[Diet (nutrition)/ja|食事]]や[[physical exercise/ja|身体運動]]などの生活習慣への介入による[[weight loss/ja|減量]]である。どのような食事が長期的な体重減少をサポートするのかは不明であり、[[Calorie restriction/ja|低カロリー食]]の有効性については議論があるが、長期的にカロリー消費を減らしたり、身体運動を増やしたりするライフスタイルの変化も、時間の経過とともに体重の戻りは緩やかであるものの、ある程度の持続的な体重減少をもたらす傾向がある。[[:en:National Weight Control Registry|全米体重コントロール登録]]の参加者の87%が10年間10%の体重減少を維持することができたが、長期的な体重減少維持のための最も適切な食事療法はまだわかっていない。米国では、食事の変更と運動の両方を組み合わせた集中的な行動介入が推奨されている。[[Intermittent fasting/ja|間欠的絶食]]は、継続的なエネルギー制限と比較して、体重減少の追加的利益はない。減量を成功させるには、どのような食事療法を行うかよりも、アドヒアランスの方が重要である。 | |||

いくつかの低カロリー食は効果的である。短期的には、[[Low-carbohydrate diet/ja|低炭水化物食]]の方が[[Low-fat diet/ja|低脂肪食]]よりも体重減少に良いと思われる。しかし、長期的には、すべてのタイプの低炭水化物食と低脂肪食が等しく有益であるように見える。さまざまな食事に関連する心臓病と糖尿病のリスクは同程度のようである。肥満者における地中海食の推進は、心臓病のリスクを低下させるかもしれない。[[sweet drink/ja|甘い飲み物]]の摂取量の減少も減量に関係している。生活様式の変更による長期的な体重減少維持の成功率は低く、2~20%である。食事および生活様式の変更は、[[pregnancy/ja|妊娠]]中の過度の体重増加を制限するのに有効であり、母子ともに転帰を改善する。肥満と心臓病の他の危険因子を併せ持つ人には、集中的な行動カウンセリングが推奨される。 | |||

=== 健康政策 === | |||

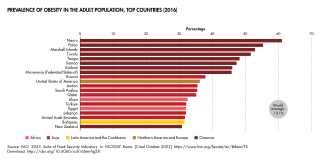

[[File:Prevalence Of Obesity In The Adult Population, Top Countries (2016).svg|thumb|330x330px|成人人口における肥満の有病率、上位国(2016年)]] | |||

[[File:Prevalence Of Obesity In The Adult Population (2016).svg|thumb|330x330px|2016年の成人人口における肥満の有病率]] | |||

肥満は、その有病率、コスト、健康への影響から、複雑な公衆衛生・政策問題である。そのため、肥満の管理には、より広い社会的背景の変化と、地域社会、地方自治体、政府による取り組みが必要である。公衆衛生の努力は、人口における肥満の有病率増加の原因となっている[[Obesity and the environment/ja|環境要因]]を理解し、是正しようとするものである。解決策は、過剰な食物エネルギー消費を引き起こし、身体活動を阻害する要因を変えることにある。取り組みとしては、連邦政府から払い戻しのある学校での給食プログラム、子どもたちへの直接的な[[junk food/ja|ジャンク]][[food marketing/ja|食品販売]]の制限、学校での砂糖入り飲料へのアクセスの減少などがある。世界保健機関(WHO)は、砂糖入り飲料への課税を推奨している。都市環境を構築する際には、公園へのアクセスを増やし、歩行者ルートを整備する努力がなされてきた。 | |||

[[:en:Mass media|マスメディア]]のキャンペーンは、肥満に影響する行動を変える効果は限定的であるように思われる。同時に、運動や食事に関する知識や意識を高めることができ、長期的には変化につながるかもしれない。キャンペーンはまた、[[Sedentary lifestyle/ja|座っている、横になっている]]時間を減らし、身体的に活動する意思にプラスの影響を与えることができるかもしれない。メニューにエネルギー情報を記載した[[Nutrition facts label/ja|栄養成分表示]]は、レストランでの食事中のエネルギー摂取量を減らすのに役立つかもしれない。[[ultra-processed foods/ja|超加工食品]]に対する政策を求める声もある。 | |||

[[ | |||

[[ | |||

==医療介入== | |||

{{Anchor|Medical interventions}} | |||

=== 薬物療法 === | |||

= | {{Main/ja|Anti-obesity medication/ja}} | ||

1930年代に肥満治療薬が登場して以来、多くの化合物が試されてきた。そのほとんどは体重を微量に減少させるものであり、そのうちのいくつかは副作用のために肥満症治療薬として販売されなくなっている。1964年から2009年の間に市場から撤去された25種類の抗肥満薬のうち、23種類は脳内の化学物質[[neurotransmitters/ja|神経伝達物質]]の機能を変化させることによって作用した。撤退に至ったこれらの薬の最も一般的な副作用は、精神障害、心臓の副作用、そして[[Substance abuse/ja|薬物乱用]]や[[drug dependence/ja|薬物依存]]であった。7つの製品に関連した死亡例が報告されている。 | |||

長期使用に有益な薬は5つある: [[orlistat/ja|オルリスタット]]、[[lorcaserin/ja|ロルカセリン]]、[[liraglutide/ja|リラグルチド]]、[[Phentermine/topiramate/ja|フェンテルミン/トピラマート]]、[[naltrexone/bupropion/ja|ナルトレキソン/ブプロピオン]]である。 | |||

その結果、1年後の体重減少は、プラセボを3.0~6.7kg(6.6~14.8ポンド)上回った。オルリスタット、リラグルチド、ナルトレキソン-ブプロピオンは米国と欧州の両方で入手可能であるが、フェンテルミン-トピラマートは米国でのみ入手可能である。ヨーロッパの規制当局はロルカセリンとフェンテルミン・トピラマートを拒絶したが、その理由の一つは、ロルカセリンでは心臓弁の問題が、ロルカセリンとフェンテルミン・トピラマートではより一般的な心臓と血管の問題が関連していたためである。ロルカセリンは米国で販売されていたが、がんとの関連から2020年に市場から削除された。オルリスタットの使用は高い確率で胃腸の副作用と関連しており、腎臓への悪影響が懸念されている。これらの薬剤が心血管疾患や死亡といった肥満の長期合併症にどのような影響を及ぼすかについての情報はないが、リラグルチドを2型糖尿病に使用した場合、心血管イベントは減少する。 | |||

2019年に[[systematic review/ja|システマティックレビュー]]で、肥満成人における様々な用量の[[fluoxetine/ja|フルオキセチン]](60 mg/d、40 mg/d、20 mg/d、10 mg/d)の体重に対する効果が比較された。プラセボと比較すると、どの用量のフルオキセチンも体重減少に寄与するようであったが、治療期間中にめまい、眠気、疲労、不眠、吐き気などの副作用を経験するリスクが増加した。しかし、これらの結論は確実性の低いエビデンスによるものであった。同じレビューで、肥満成人の体重に対するフルオキセチンの効果を、他の[[Anorectic/ja|抗肥満薬]]、[[Omega-3 fatty acid/ja|オメガ-3]]ゲル、治療を受けていない場合と比較した場合、著者らはエビデンスの質が低いため、決定的な結果に到達できなかった。 | |||

統合失調症治療用の抗精神病薬の中で[[clozapine/ja|クロザピン]]は最も有効であるが、肥満が主な特徴である[[metabolic syndrome/ja|メタボリックシンドローム]]を引き起こすリスクも最も高い。クロザピンの服用により体重が増加した人は、[[metformin/ja|メトホルミン]]を服用することにより、メタボリックシンドロームの5つの構成要素のうち3つ(ウエスト周囲径、空腹時血糖、空腹時トリグリセリド)が改善すると報告されている。 | |||

=== 手術=== | |||

肥満に対する最も効果的な治療法は[[bariatric surgery/ja|肥満手術]]である。手術の種類には、[[laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding/ja|腹腔鏡下調節可能胃バンディング術]]、[[Roux-en-Y gastric bypass/ja|ルークス-エン-Y胃バイパス術]]、[[vertical-sleeve gastrectomy/ja|縦型スリーブ胃切除術]]、[[biliopancreatic diversion/ja|胆膵転換術]]などがある。高度肥満に対する手術は、長期的な体重減少、肥満に関連した病態の改善、および全死亡率の低下と関連している;しかしながら、代謝健康の改善は体重減少によるものであり、手術によるものではない。ある研究では、標準的な減量法と比較した場合、10年後の体重減少率は14%~25%(実施した手術の種類による)、全死因死亡率は29%減少した。合併症は約17%の症例で起こり、7%の症例で再手術が必要である。 | |||

==疫学== | |||

{{Anchor|Epidemiology}} | |||

{{Main/ja|Epidemiology of obesity/ja}} | |||

[[File:Obesity rate.png|thumb|BMIが30を超える成人のシェア(2016年)]] | |||

{{Global Heat Maps by Year| title=| table=Obesity Males.tab| column=percent_overweight| columnName=BMI>25の割合| year=2014}} | |||

それ以前の歴史的な時代には、肥満は健康上の問題としてすでに認識されていたものの、ごく一部のエリートによってのみ達成されるまれなものであった。しかし、[[:en:Early Modern period|近世]]に繁栄が進むにつれて、肥満はますます多くの人々に影響を及ぼすようになった。1970年代以前は、肥満は最も裕福な国でも比較的まれな状態であり、肥満が存在するとしても裕福な人々の間で起こる傾向があった。その後、さまざまな出来事が重なり、人間の状態が変わり始めた。第一世界の人々の平均BMIが上昇し始め、その結果、過体重や肥満の人の割合が急増したのである。 | |||

[[ | |||

1997年、WHOは肥満を世界的な疫病として正式に認定した。2008年現在、WHOは少なくとも5億人(10%以上)の成人が肥満であり、男性よりも女性の方が肥満率が高いと推定している。1980年から2014年の間に、肥満の世界的有病率は2倍以上に増加した。2014年には、6億人以上の成人が肥満であり、これは世界の成人人口の約13%に相当する。2015-2016年現在のアメリカにおける成人の割合は、全体で約39.6%(男性37.9%、女性41.1%)である。2000年、[[World Health Organization/ja|世界保健機関]](WHO)は、[[overweight/ja|過体重]]と肥満が、[[undernutrition/ja|栄養不足]]や[[infectious diseases/ja|感染症]]といった、より伝統的な[[public health/ja|公衆衛生]]の懸念に取って代わり、健康不良の最も重大な原因のひとつになっていると述べた。 | |||

また、肥満の割合は少なくとも50歳、60歳までは年齢とともに増加し、アメリカ、オーストラリア、カナダでは重度の肥満が全体の肥満率よりも速く増加している。[[:en:OECD|OECD]]は少なくとも2030年まで肥満率が増加すると予測しており、特にアメリカ、メキシコ、イギリスではそれぞれ47%、39%、35%に達すると予測している。 | |||

かつては高所得国だけの問題と考えられていた肥満率が世界的に上昇し、先進国と発展途上国の両方に影響を及ぼしている。こうした増加は、都市部で最も顕著に現れている。 | |||

性別による違いも肥満の有病率に影響を与える。世界的には男性より女性の方が肥満者が多いが、その数は肥満の測定方法によって異なる。 | |||

==歴史== | |||

{{Anchor|History}} | |||

===語源=== | |||

= | ''Obesity''は[[:ja:ラテン語|ラテン語]]の''obesitas''に由来し、「がっしりした、太った、ふくよかな」を意味する。''Ēsus''は''edere''(食べる)の過去分詞で、それに''ob''(超える)が加わったものである。''[[:en:The Oxford English Dictionary|オックスフォード英語辞典]]'には1611年に[[:en:Randle Cotgrave|Randle Cotgrave]]によって初めて使われたと記録されている。 | ||

===歴史的姿勢=== | |||

[[File:Charles Mellin (attributed) - Portrait of a Gentleman - Google Art Project.jpg|thumb|upright=1.0|alt=二重あごと口ひげが目立つ、非常に肥満した紳士で、左脇に剣を持った黒い服を着ている。|[[:en:Middle Ages|中世]]から[[:en:Renaissance|ルネサンス]]期にかけて、''トスカーナの将軍[[:en:Alessandro del Borro|アレッサンドロ・デル・ボッロ]]''(シャルル・メリン作とされる、1645年]] | |||

[[File:Venus von Willendorf 01.jpg|thumb|upright=1.0|alt=石に彫られたミニチュアの置物には、肥満した女性が描かれていた。|''[[:en:Venus of Willendorf|ヴィレンドルフのヴィーナス]]''は紀元前24,000年~22,000年に作られた。]] | |||

[[:en:Ancient Greek medicine|古代ギリシア医学]]は肥満を医学的疾患として認めており、古代エジプト人も同じように肥満を見ていたと記録している。[[:en:Hippocrates|ヒポクラテス]]は「肥大は病気そのものであるだけでなく、他の病気の前触れである」と書いた。インドの外科医[[:en:Sushruta|スシュルタ]](紀元前6世紀)は、肥満を糖尿病や心臓疾患と関連づけた。彼は肥満とその副作用を治すために肉体労働を勧めた。人類の歴史の大半において、人類は食糧不足と闘ってきた。そのため、肥満は歴史的に富と繁栄の証とみなされてきた。古代東アジア文明では、高官の間で一般的であった。17世紀、イギリスの医学者[[:en:Tobias Venner|トビアス・ヴェナー]]は、出版された英語の本の中で、社会的な病気としてこの言葉を最初に言及した一人とされている。 | |||

[[File:Charles Mellin (attributed) - Portrait of a Gentleman - Google Art Project.jpg|thumb|upright=1.0|alt= | |||

[[File:Venus von Willendorf 01.jpg|thumb|upright=1.0|alt= | |||

[[Ancient Greek medicine]] | |||

[[:en:Industrial Revolution|産業革命]]が始まると、国家の軍事力と経済力が兵士や労働者の体格と体力の両方に左右されることがわかった。平均的な体格指数を現在の低体重とされるものから、現在の標準的な範囲まで高めることが、工業化社会の発展に重要な役割を果たした。こうして身長と体重は、先進国では19世紀を通じて増加した。20世紀には、集団が遺伝的に可能な身長に達すると、体重は身長よりもはるかに増加し始め、その結果肥満が生じた。1950年代には、先進国の富裕化が進み、子どもの死亡率は低下したが、体重が増加するにつれて、心臓病や腎臓病が多発するようになった。 | |||

この時期、保険会社は体重と寿命の関係に気づき、肥満者に対する保険料を値上げした。 | |||

歴史上、多くの文化が肥満を性格的欠陥の結果とみなしてきた。[[:en:Ancient Greek comedy|古代ギリシャの喜劇]]に登場する''obesus''つまり太った人物は大食漢であり、嘲笑の的であった。キリスト教時代には、食べ物は[[:en:Sloth (deadly sin)|怠惰]]や[[:en:lust|欲望]]の罪への入り口と見なされていた。現代の西洋文化では、過剰な体重は魅力がないとみなされることが多く、肥満は一般的にさまざまな否定的なステレオタイプと結びついている。あらゆる年齢の人々が社会的汚名に直面し、いじめの標的にされたり、仲間から敬遠されたりすることがある。 | |||

健康的な体重に関する欧米社会の一般的な認識と、理想的とされる体重に関する認識は異なっており、両者は20世紀に入ってから変化している。理想とされる体重は、1920年代以降低くなっている。このことは、ミス・アメリカコンテスト受賞者の平均身長が1922年から1999年にかけて2%増加したのに対し、平均体重は12%減少したことからもわかる。一方、健康的な体重に関する人々の見方は逆に変化している。イギリスでは、自分が太りすぎだと思う体重は、1999年よりも2007年の方が大幅に増えている。このような変化は、脂肪率の増加により、余分な体脂肪が普通であると受け入れられるようになったためと考えられている。 | |||

アフリカの多くの地域では、肥満はいまだに富と幸福の証とみなされている。特に[[HIV/ja|HIV]]の流行が始まって以来、その傾向が強くなっている。 | |||

===芸術=== | |||

== | 20,000~35,000年前の人体の最初の彫刻表現は、肥満した女性を描いている。この[[:en:Venus figurines|ヴィーナスの彫刻]]を、豊穣を強調する傾向のためとする人もいれば、当時の人々の「太りやすさ」を表していると感じる人もいる。しかし、ギリシア・ローマ美術には豊満さが見られない。この傾向は、キリスト教ヨーロッパの歴史の大半を通じて続き、社会経済的地位の低い人々だけが肥満として描かれた。 | ||

[[:en:Renaissance|ルネサンス]]期には、[[:en:Henry VIII of England|イギリスのヘンリー8世]]や[[:en:Alessandro dal Borro|アレッサンドロ・ダル・ボッロ]]の肖像画に見られるように、上流階級の一部が大柄であることを誇示し始めた。[[:en:Peter Paul Rubens|ルーベンス]](1577年-1640年)は定期的に大柄な女性を描いており、そこから[[:en:Peter Paul Rubens#Work|ルーベネスク]]という言葉が生まれた。しかし、これらの女性たちは、豊穣と関係のある「砂時計」の形を維持していた。19世紀、西洋世界では肥満に対する見方が変わった。何世紀にもわたって肥満が富と社会的地位の代名詞とされてきた後、スリムであることが望ましい標準とみなされるようになった。1819年の版画「The Belle Alliance, or the Female Reformers of Blackburn!!!」で、画家[[:en:George Cruikshank|George Cruikshank]]は[[:en:Blackburn|Blackburn]]の女性改革者たちの活動を批判し、彼女たちを女性らしくないと描く手段として太り方を用いた。 | |||

==社会と文化== | |||

{{Anchor|Society and culture}} | |||

===経済的影響=== | |||

=== | 健康への影響に加え、肥満は雇用の不利やビジネスコストの増加など、多くの問題を引き起こす。こうした影響は、個人、企業、政府など、社会のあらゆるレベルで感じられる。 | ||

2005年、米国における肥満に起因する医療費は推定1,902億ドル(全医療費の20.6%)、カナダにおける肥満のコストは1997年に推定20億カナダドル(総医療費の2.4%)であった。2005年のオーストラリアにおける過体重と肥満の年間直接費用は合計210億豪ドルであった。また、過体重・肥満のオーストラリア人は、356億豪ドルの政府補助金を受け取っている。ダイエット製品への年間支出額の推定範囲は、米国だけで400億ドルから1,000億ドルである。 | |||

[[:en:The Lancet|ランセット誌]] 2019年の肥満に関する委員会は、[[:en:WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control|WHOたばこ規制枠組条約]]をモデルとして、肥満と栄養不足に対処することを各国に約束し、政策立案から食品業界を明確に除外した世界的な条約を求めた。彼らは、肥満の世界的なコストは年間2兆ドル、世界GDPの約2.8%と見積もっている。 | |||

[[The Lancet]] | |||

肥満予防プログラムは、肥満に関連した病気の治療費を削減することが分かっている。しかし、長生きすればするほど医療費は増える。したがって研究者たちは、肥満を減らすことは国民の健康を改善するかもしれないが、医療費全体の支出を減らす可能性は低いと結論づけている。食習慣や消費習慣を抑制し、経済的負担を相殺する努力として、[[:en:sugary drink tax|砂糖入り飲料税]]のような罪税が世界的に特定の国で実施されている。 | |||

[[File:Wide Chair.jpg|thumb|left|upright=1.3|alt=普通サイズの椅子の横に、幅の広い椅子が置かれている。|サービスでは、かなり幅の広い椅子など、特殊な設備で肥満の人に対応している。]] | |||

[[File:Wide Chair.jpg|thumb|left|upright=1.3|alt= | 肥満は社会的汚名を着せられ、雇用面でも不利になる。標準体重の労働者と比較すると、肥満の労働者は平均して欠勤率が高く、障害休暇を多く取るため、雇用者のコストが増加し、生産性が低下する。デューク大学の従業員を調査した研究によると、BMIが40 kg/m<sup>2</sup>を超える人は、BMIが18.5-24.9 kg/m<sup>2</sup>の人に比べて、2倍の[[労災]]請求を行った。また、労働損失日数も12倍以上であった。このグループで最も多かった怪我は転倒と持ち上げによるもので、下肢、手首または手、背中に影響を及ぼしていた。アラバマ州職員保険委員会は、肥満の労働者に対し、減量と健康改善のための措置を講じない限り、本来無料であるはずの健康保険料を月25ドル徴収する計画を承認し、物議を醸している。この措置は2010年1月から開始され、BMIが35 kg/m<sup>2</sup>を超え、1年経っても健康状態の改善が見られない州職員に適用される。 | ||

肥満の人は採用されにくく、昇進しにくいという調査結果もある。また、肥満の人は肥満でない人に比べて、同等の仕事をした場合の給与が低く、肥満の女性は平均で6%、肥満の男性は3%低い。 | |||

航空業界、医療業界、食品業界など、特定の業界には特別な懸念がある。肥満率の上昇により、航空会社は燃料費の上昇と座席幅を広げる圧力に直面している。2000年には、肥満の乗客の体重増加により、航空会社は2億7500万米ドルの損失を被った。医療業界は、特別なリフト装置や[[bariatric ambulance/ja|肥満救急車]]など、重度の肥満患者を扱うための特別な設備に投資しなければならなくなった。レストランは、肥満の原因を作ったとする訴訟により、コストが増大している。2005年、アメリカ議会は肥満に関する食品業界への民事訴訟を防ぐための法案を審議したが、法制化には至らなかった。 | |||

2013年に[[:en:American Medical Association|アメリカ医師会]]が肥満を慢性疾患に分類したことで、健康保険会社が肥満の治療やカウンセリング、手術の費用を負担する可能性が高まり、脂肪治療薬や遺伝子治療法の研究開発費も、保険会社がその費用を補助することでより手頃な価格になると考えられている。ただし、AMAの分類には法的拘束力はないため、医療保険会社には治療や処置の保険適用を拒否する権利が残っている。 | |||

2014年、欧州司法裁判所は、病的肥満は障害であるとの判決を下した。同裁判所は、従業員の肥満が「他の労働者と対等な立場での職業生活への完全かつ効果的な参加」を妨げる場合、それは障害とみなされ、そのような理由で解雇することは差別的であるとした。 | |||

低所得国では、肥満は富のシグナルとなりうる。2023年の実験的研究によると、ウガンダでは肥満の人ほどクレジットを利用しやすいことがわかった。 | |||

===サイズの受容=== | |||

=== | {{See also/ja|Fat acceptance movement/ja|Social stigma of obesity/ja|Health at Every Size/ja|Fat fetishism/ja}} | ||

{{See also|Fat acceptance movement|Social stigma of obesity|Health at Every Size|Fat fetishism}} | [[File:PresidentTaftTelephoneCrop.jpg|thumb|upright=1|[[:en:United States President|アメリカ大統領]]の[[:en:William Howard Taft|ウィリアム・ハワード・タフト]]は、太っているとよく揶揄された。]] | ||

[[File:PresidentTaftTelephoneCrop.jpg|thumb|upright=1|[[United States President]] [[William Howard Taft]] | [[File:Wahlkampf_Landtagswahl_NRW_2022_-_Bündnis_90-Die_Grünen_-_Heumarkt_Köln_2022-05-13-4484.jpg|thumb|upright=1|ドイツの政治家[[:en:Ricarda Lang|リカルダ・ラング]]は、インターネット上で脂肪を辱める行為の被害者である。]] | ||

[[File:Wahlkampf_Landtagswahl_NRW_2022_-_Bündnis_90-Die_Grünen_-_Heumarkt_Köln_2022-05-13-4484.jpg|thumb|upright=1| | |||

脂肪受容運動の主な目的は、太りすぎや肥満の人に対する差別を減らすことである。しかし、この運動の中には、肥満と健康上の悪い結果との間に確立された関係に異議を唱えようとするものもある。 | |||

肥満の容認を推進する団体は数多く存在する。それらは20世紀後半にその存在感を増してきた。米国を拠点とする[[:en:National Association to Advance Fat Acceptance|全米ファット・アクセプタンス推進協会]] (NAAFA)は1969年に結成され、サイズ差別をなくすことを目的とした公民権団体であると自称している。 | |||

[[:en:International Size Acceptance Association|国際サイズ受容協会]](ISAA)は1997年に設立された[[:en:non-governmental organization|非政府組織]](NGO)である。よりグローバルな方向性を持ち、サイズ受容を促進し、体重による差別をなくすことを使命としている。これらの団体はしばしば、アメリカの[[:en:Americans With Disabilities Act|障害者自立支援法(ADA)]]の下で肥満を障害として認めるよう主張している。しかし、アメリカの法制度は、この差別禁止法を肥満にまで拡大するメリットを、潜在的な公衆衛生上のコストが上回ると判断している。 | |||

===業界による研究への影響=== | |||

=== | 2015年、''ニューヨーク・タイムズ''紙は、2014年に設立された非営利団体[[:en:Global Energy Balance Network|グローバル・エネルギー・バランス・ネットワーク]]に関する記事を掲載した。この団体は、肥満を回避し、健康であるためには、摂取カロリーを減らすことよりも、運動を増やすことに重点を置くべきだと提唱している。この団体は[[Coca-Cola Company|コカ・コーラ社]]から少なくとも150万ドルの資金提供を受けて設立され、同社は2008年以来、設立者の2人の科学者グレゴリー・A・ハンドと[[:en:Steven Blair|スティーブン・ブレア]]に400万ドルの研究資金を提供している。 | ||

===報告書=== | ===報告書=== | ||

Latest revision as of 14:15, 7 March 2024

| 肥満 | |

|---|---|

| |

| 最適、過体重、肥満を表すシルエットとウエスト周囲径の値 | |

| Specialty | 内分泌学 |

| Symptoms | Increased fat |

| Complications | Cardiovascular disease/ja, type 2 diabetes/ja, obstructive sleep apnea/ja, ある種のcancer/ja, osteoarthritis/ja, うつ病 |

| Causes | エネルギー密度の高い食品の過剰摂取、座りがちな仕事とライフスタイル、運動不足、交通手段の変化、都市化、支援政策の欠如、健康的な食事へのアクセス不足、遺伝 |

| Diagnostic method | BMI > 30 kg/m2 |

| Prevention | 社会の変化、食品業界の変化、健康的なライフスタイルへのアクセス、個人の選択 |

| Treatment | 食事療法、運動療法、薬物療法、手術 |

| Prognosis | 平均寿命が短くなる |

| Frequency | 10億人以上 / 12.5% (2022) |

| Deaths | 年間2.8百万人 |

| aシリーズの一部である。 |

| 体重 |

|---|

肥満とは、過剰な体脂肪が健康に悪影響を及ぼす可能性があるほど蓄積している医学的状態であり、時に病気とみなされる。体重を身長の2乗で割った体格指数(BMI)が30 kg/m2を超えると肥満と分類され、25–30 kg/m2の範囲が過体重と定義される。一部の東アジア諸国では、より低い値を用いて肥満を計算している。肥満は身体障害の主な原因であり、特に心血管系疾患、2型糖尿病、閉塞性睡眠時無呼吸症候群、ある種のがん、変形性関節症などさまざまな病気や状態と関連している。

肥満には個人的、社会経済的、環境的原因がある。知られている原因としては、食事、身体活動、自動化、都市化、遺伝的感受性、薬、精神障害、経済政策、内分泌障害、内分泌かく乱化学物質への暴露などがある。

常時、肥満者の大多数が減量を試み、成功することが多いが、減量を長期的に維持することはまれである。肥満を予防するための効果的で明確な、エビデンスに基づいた介入はない。肥満予防には、社会、地域社会、家族、個人レベルでの介入を含む複雑なアプローチが必要である。エクササイズと同様に食事の変更が、医療専門家によって推奨される主な治療法である。食事の質は、脂肪や糖分の多い食品などエネルギー密度の高い食品の摂取を減らし、食物繊維の摂取を増やすことで改善できる。薬物療法は、適切な食事療法とともに、食欲を減退させたり脂肪の吸収を減少させたりするために用いることができる。食事療法、運動療法、薬物療法が効果的でない場合は、胃バルーンや外科手術を行って胃の容積や腸の長さを減らし、早く満腹感を感じたり、食物からの栄養吸収能力を低下させたりすることがある。

肥満は世界的に予防可能な死因のトップであり、成人および小児の割合が増加している。2022年には、世界で10億人以上が肥満であり(成人8億7900万人、小児1億5900万人)、1990年に登録された成人の症例の2倍以上(小児の症例の4倍)であった。肥満は男性よりも女性に多い。今日、肥満は世界のほとんどの地域でスティグマである。逆に、過去も現在も、肥満を富と豊穣の象徴とみなして好意的にとらえている文化もある。世界保健機関、アメリカ、カナダ、日本、ポルトガル、ドイツ、欧州議会、医学会、例えばアメリカ医師会は肥満を病気として分類している。英国のように、そうでない国もある。

分類

| カテゴリ | BMI (kg/m2) |

|---|---|

| アンダーウエイト | < 18.5 |

| 標準体重 | 18.5 – 24.9 |

| オーバーウエイト | 25.0 – 29.9 |

| 肥満 (クラス I) | 30.0 – 34.9 |

| 肥満 (クラス II) | 35.0 – 39.9 |

| 肥満 (クラス III) | ≥ 40.0 |

肥満とは一般的に、健康に影響を及ぼす可能性のある体脂肪の実質的な蓄積として定義される。医療機関では、体格指数(BMI)、つまりキログラム単位の体重とメートル単位の身長の2乗の比率に基づいて、人々を肥満として分類する傾向がある。成人の場合、世界保健機関(WHO)はBMI 25以上を「過体重」、BMI 30以上を「肥満」と定義している。米国疾病管理予防センター(CDC)では、BMIをもとに肥満をさらに細分化しており、BMI30~35をクラス1肥満、35~40をクラス2肥満、40以上をクラス3肥満と呼んでいる。

子どもの場合、肥満の指標は身長と体重とともに年齢を考慮する。5~19歳の子どもについては、WHOはBMIが年齢の中央値を2標準偏差上回ることを肥満と定義している(5歳児のBMIは約18、19歳児は約30)。5歳未満の子どもの場合、WHOは身長の中央値より3標準偏差高い体重を肥満と定義している。

WHOの定義には、特定の団体によっていくつかの修正が加えられている。外科的な文献では、クラスⅡとⅢ、またはクラスⅢのみの肥満を、正確な値がまだ論争されているさらなるカテゴリーに分類している。

- BMIが35以上または40以上の場合は、高度肥満である。

- BMI≧35 kg/m2で、肥満に関連した健康状態を経験しているか、または≧40 kg/m2または≧45 kg/m2は病的肥満である。

- BMIが45以上または50 kg/m2以上は超肥満である。

アジア人集団は白人と比べてより低いBMI値で健康上の悪影響が現れるため、一部の国々では肥満の定義を見直しています。日本では肥満をBMI25kg/m2以上と定義し、中国ではBMI28kg/m2以上を肥満としている。

学者界で好まれている肥満の指標は体脂肪率(BF%)であり、体重に対する脂肪の総重量の割合である。女性は32%、男性は25%を超えると、一般的に肥満を示すと考えられている。

BMIは除脂肪体重、特に筋肉量の個人差を無視している。激しい肉体労働やスポーツに従事している人は、脂肪が少ないにもかかわらずBMI値が高いことがある。例えば、NFL選手の半数以上が「肥満」(BMI≧30)に分類され、BMIの指標によれば4人に1人が「極度の肥満」(BMI≧35)に分類される。しかし、彼らの平均体脂肪率は14%であり、健康的な範囲と考えられている。同様に、相撲力士はBMIでは「重度肥満」または「超重度肥満」に分類されるかもしれないが、代わりに体脂肪率を用いると多くの力士は肥満には分類されない(体脂肪率が25%未満である)。一部の力士は、非力士の比較群と比べて体脂肪がなく、除脂肪体重が多いためにBMI値が高いことが判明した。

健康への影響

肥満は、さまざまな代謝性疾患、心血管疾患、変形性関節症、アルツハイマー病、うつ病、およびある種のがんの発症リスクを高める。肥満の程度や併存疾患の有無にもよるが、肥満は推定2~20年の寿命短縮と関連している。高BMIは、食事や身体活動によって引き起こされる疾患のリスクの指標ではあるが、直接的な原因ではない。

死亡率

肥満は世界的に主要な予防可能な死因の一つである。死亡リスクは、非喫煙者ではBMI20~25kg/m2で最も低く、現在喫煙者ではBMI24~27kg/m2で最も低く、どちらかに変化するとリスクは増加する。これは少なくとも4大陸で当てはまるようである。他の研究によると、BMIおよびウエスト周囲径と死亡率との関連はU字型またはJ字型であるが、ウエスト-ヒップ比およびウエスト-身長比と死亡率との関連はよりポジティブである。アジア人では、健康への悪影響のリスクは22~25kg/m2の間で増加し始める。2021年、世界保健機関(WHO)は、肥満が毎年少なくとも280万人の死亡を引き起こすと推定した。平均して、肥満は平均余命を6~7年縮め、BMIが30~35 kg/m2では平均余命を2~4年縮め、重度の肥満(BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2)では平均余命を10年縮める。

罹患率

肥満は多くの身体的・精神的疾患のリスクを高める。このような併存疾患は、メタボリックシンドロームに最もよく見られる: 2型糖尿病、高血圧、高コレステロール血症、高トリグリセリド血症が含まれる。RAK病院の研究によれば、肥満の人は長いCOVIDを発症するリスクが高い。CDCは、肥満がCOVID-19の重症化に対する唯一最強の危険因子であることを明らかにした。

合併症は、肥満が直接の原因であるか、あるいは食生活の乱れや座りがちな生活習慣など共通の原因を持つメカニズムを通じて間接的に関連している。肥満と特定の疾患との関連性の強さは様々である。最も強いもののひとつは2型糖尿病との関連である。過剰な体脂肪は、男性では糖尿病の症例の64%、女性では77%を引き起こしている。

健康への影響は大きく2つのカテゴリーに分類される:脂肪量の増加の影響に起因するもの(変形性関節症、閉塞性睡眠時無呼吸症候群、社会的汚名など)と脂肪細胞の増加によるもの(糖尿病、がん、心血管系疾患、非アルコール性脂肪肝疾患)。体脂肪の増加はインスリンに対する身体の反応を変化させ、潜在的にインスリン抵抗性を引き起こす。脂肪の増加はまた、炎症性状態や血栓性状態を引き起こす。

| 医療分野 | 状態 | 医療分野 | 状態 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 循環器学 | Dermatology/ja | ||

| 内分泌学とreproductive medicine/ja | Gastroenterology/ja | ||

| Neurology/ja | Oncology/ja | ||

| Psychiatry/ja |

|

Respirology/ja |

|

| Rheumatology/jaとorthopedics/ja |

|

Urology/jaとNephrology/ja |

健康の指標

新しい研究では、臨床医がより健康的な肥満者を特定する方法と、肥満者を一枚岩として扱わない方法に焦点が当てられている。肥満による医学的合併症を経験しない肥満者を(代謝的に)健康な肥満と呼ぶことがあるが、このグループが(特に高齢者において)どの程度存在するかについては論争がある。メタボ健常者とみなされる人の数は、使用される定義によって異なり、普遍的に受け入れられる定義はない。代謝異常が比較的少ない肥満者も多数存在し、医学的合併症のない肥満者も少数派である。米国臨床内分泌学会のガイドラインでは、2型糖尿病発症リスクの評価方法を検討する際に、肥満患者に対してリスク層別化を行うよう医師に呼びかけている。

2014年、BioSHaRE-EU(マギル大学保健センター研究所傘下のチームであるMaelstrom Researchがスポンサー)は、健康的肥満の定義を2つに分けた:

| 厳格でない | より厳格に | |

|---|---|---|

| 血圧は、医薬品の助けを借りずに次のように測定した。 | ||

| 全体 (mmHg) | ≤ 140 | ≤ 130 |

| Systolic/ja (mmHg) | N/A | ≤ 85 |

| Diastolic/ja (mmHg) | ≤ 90 | N/A |

| 血糖値は、医薬品の助けを借りずに次のように測定した。 | ||

| 血糖値 (mmol/L) | ≤ 7.0 | ≤ 6.1 |

| トリグリセリドは、医薬品の助けを借りることなく、次のようにして測定した。 | ||

| 空腹時 (mmol/L) | ≤ 1.7 | |

| 非空腹時 (mmol/L) | ≤ 2.1 | |

| 高比重リポ蛋白は、医薬品の助けを借りずに以下のように測定した。 | ||

| 男性 (mmol/L) | > 1.03 | |

| 女性 (mmol/L) | > 1.3 | |

| いかなる心血管系疾患の診断も受けていない。 | ||

BioSHaREは、この基準を設定するために、年齢とタバコの使用をコントロールし、両者が肥満に伴うメタボリックシンドロームにどのような影響を及ぼすかを研究した。メタボ健常肥満の定義には、BMIではなくウエスト周囲径に基づくものなど、他の定義も存在するが、これは特定の個人においては信頼性に欠ける。

肥満者における健康のもう一つの識別指標はカフ筋力であり、これは肥満者の体力と正の相関がある。一般的に身体組成は、代謝的に健康な肥満の存在を説明するのに役立つという仮説がある-代謝的に健康な肥満者は、メタボリックシンドロームの肥満者と同等の全体的な脂肪量を有するにもかかわらず、異所性脂肪(脂肪組織以外の組織に蓄積された脂肪)の量が少ないことがしばしば発見される。

生存のパラドックス

一般集団における肥満の健康への悪影響は、利用可能な研究エビデンスによって十分に裏付けられているが、特定のサブグループにおける健康転帰は、BMIが上昇すると改善するようであり、これは肥満生存パラドックスとして知られる現象である。このパラドックスは、1999年に血液透析を受けている過体重および肥満の人々において初めて報告され、その後、心不全および末梢動脈疾患(PAD)を有する人々においても見出されている。

心不全患者では、BMIが30.0から34.9の人は標準体重の人より死亡率が低かった。これは、病気が進行するにつれて体重が減少することが多いためと考えられている。他の心臓病でも同様の結果が得られている。クラスIの肥満で心臓病を持つ人は、心臓病を持つ標準体重の人よりも、さらなる心臓病の発生率は高くない。しかし、肥満の程度が高い人では、さらなる心血管イベントのリスクが増加する。心臓バイパス手術後でも、過体重や肥満では死亡率の増加はみられない。ある研究では、生存率の向上は、肥満の人が心臓イベント後に受ける治療がより積極的であることによって説明できるとしている。別の研究では、PAD患者の慢性閉塞性肺疾患(COPD)を考慮すると、肥満の利点はもはや存在しないことがわかった。

原因

肥満の「a calorie is a calorie」モデルは、ほとんどの肥満の原因として、過剰な食物エネルギー摂取と身体活動不足の組み合わせを仮定している。遺伝、医学的理由、精神疾患によるものは限られている。対照的に、社会レベルでの肥満率の増加は、簡単に手に入り、口にしやすい食事、増加した自動車への依存、機械化された製造業によるものと考えられている。

世界的な肥満率上昇の原因として、睡眠不足、内分泌攪乱物質、特定の薬物(非定型抗精神病薬など)の使用量の増加、周囲温度の上昇、人口動態の変化、初産婦の年齢上昇、タバコ喫煙率の低下、人口統計学的変化、初産婦の年齢上昇、環境からのエピジェネティックな調節異常の変化、同系交配による表現型変異の増加、ダイエットに対する社会的圧力などである。ある研究によると、これらのような要因は、過剰な食物エネルギー摂取や運動不足と同じくらい大きな役割を果たしている可能性がある。しかし、肥満の原因として提案されているものの影響の相対的な大きさは様々であり、確定的な見解を出すにはヒトを対象としたランダム化比較試験が必要であるため、不確かである。

内分泌学会によれば、「肥満は、単に過剰な体重の受動的蓄積から生じるのではなく、エネルギー恒常性システムの障害であることを示唆する証拠が増えている」という。

食事

|

No data

<1,600 (<6,700)

1,600–1,800 (6,700–7,500)

1,800–2,000 (7,500–8,400)

2,000–2,200 (8,400–9,200)

2,200–2,400 (9,200–10,000)

2,400–2,600 (10,000–10,900)

|

2,600–2,800 (10,900–11,700)

2,800–3,000 (11,700–12,600)

3,000–3,200 (12,600–13,400)

3,200–3,400 (13,400–14,200)

3,400–3,600 (14,200–15,100)

>3,600 (>15,100)

|

口当たりのよい高カロリー食品(特に脂肪、砂糖、特定の動物性タンパク質)に対する過剰な食欲は、世界的な肥満を引き起こす主な要因と考えられているが、これはおそらく、食べたいという衝動に影響する神経伝達物質のバランスが崩れているためであろう。一人当たりの食事エネルギー供給量は、地域や国によって著しく異なる。また、時代とともに大きく変化している。1970年代初頭から1990年代後半にかけて、東欧を除く世界のすべての地域で、1人1日あたりに利用可能な平均食物エネルギー(買物量)は増加した。1996年には、米国が一人当たり3,654 calories (15,290 kJ)で最も利用可能量が多かった。2003年にはさらに増加し、3,754 calories (15,710 kJ)となった。1990年代後半には、ヨーロッパ人は1人当たり3,394 calories (14,200 kJ)、アジアの発展途上地域では1人当たり2,648 calories (11,080 kJ)、サハラ以南のアフリカでは1人当たり2,176 calories (9,100 kJ)であった。食品の総エネルギー消費量は肥満と関係があることがわかっている。

食事ガイドラインが普及しても、過食や食生活の選択ミスの問題に対処することはほとんどできなかった。1971年から2000年にかけて、米国の肥満率は14.5%から30.9%に増加した。同じ期間に、食品の平均消費エネルギー量も増加している。女性の平均増加量は1日あたり335 calories (1,400 kJ)(1971年では1,542 calories (6,450 kJ)、2004年では1,877 calories (7,850 kJ))であり、男性の平均増加量は1日あたり168 calories (700 kJ)(1971年では2,450 calories (10,300 kJ)、2004年では2,618 calories (10,950 kJ))であった。この余分な食物エネルギーのほとんどは、脂肪消費よりもむしろ炭水化物消費の増加によるものである。これらの余分な炭水化物の主な供給源は、アメリカの若年成人の1日の食物エネルギーのほぼ25%を占めるようになった甘味飲料と、ポテトチップスである。清涼飲料水、果実飲料、アイスティーなどの甘味飲料の消費は、肥満率の上昇、メタボリックシンドロームや2型糖尿病のリスクの上昇に寄与していると考えられている。ビタミンD欠乏症は肥満に関連する疾患と関連している。

社会がエネルギー密度が高い、大盛り、ファーストフードの食事にますます依存するようになるにつれて、ファストフードの消費と肥満の関連性がより懸念されるようになる。米国では、1977年から1995年の間に、ファストフードの消費量は3倍になり、これらの食事からの食物エネルギー摂取量は4倍になった。

アメリカやヨーロッパにおける農業政策や技術は、食料価格の低下をもたらした。アメリカでは農業法案によるトウモロコシ、大豆、小麦、米への補助金によって、加工食品の主な供給源は果物や野菜に比べて安価になった。カロリー計算法や栄養成分表示は、食品のエネルギーがどれだけ消費されているかを意識するなど、より健康的な食品を選択するよう人々を誘導しようとするものである。

肥満の人は、標準体重の人に比べて、常に自分の食事消費量を過少に報告する。これは、熱量計室内で行われた人体実験と直接観察の両方によって裏付けられている。

座りっぱなしのライフスタイル

座りがちなライフスタイルは、肥満に大きな役割を果たしている可能性がある。世界的に、身体的負荷の少ない仕事へのシフトが大きく進んでおり、現在、世界人口の少なくとも30%が運動不足である。この主な原因は、機械化された交通手段の増加や、家庭内での省力化技術の普及である。子どもたちにおいては、身体活動レベルの低下(特に歩行量と体育の減少が著しい)が見られるが、これは安全への懸念、社会的相互作用の変化(近所の子どもたちとの関係が希薄になるなど)、不適切な都市設計(安全な身体活動のための公共スペースが少なすぎるなど)が原因であると考えられる。活動的な余暇身体活動における世界の傾向は、あまり明確ではない。世界保健機関(WHO)は、世界中の人々があまり活動的でないレクリエーションに興じていることを示しているが、フィンランドの調査では増加しており、米国の調査では余暇の身体活動に大きな変化はないとしている。子どもの身体活動は、重要な要因ではないかもしれない。

子どもも大人も、テレビ視聴時間と肥満リスクには関連がある。メディアへの露出が増えると小児肥満の割合が増加し、その割合はテレビ視聴時間に比例して増加する。

遺伝学

他の多くの病状と同様に、肥満は遺伝的要因と環境的要因の相互作用の結果である。食欲や代謝を制御する様々な遺伝子のPolymorphism (biology)/ja多型は、十分な食物エネルギーが存在する場合に肥満の素因となる。2006年の時点で、ヒトゲノム上のこれらの部位のうち41以上が、好ましい環境が存在する場合に肥満の発症に関連するとされている。FTO遺伝子(脂肪量および肥満関連遺伝子)を2コピー持つ人は、リスク対立遺伝子を持たない人に比べて、平均で体重が3-4 kg多く、肥満のリスクが1.67倍高いことが判明している。遺伝によるBMIの差は、調査した集団によって6%から85%まで様々である。

肥満は、プラダー・ウィリー症候群、バルデ・ビードル症候群、コーエン症候群、MOMO症候群などのいくつかの症候群における主要な特徴である(これらの疾患を除外するために「非症候群性肥満」という用語が使われることがある)。早期発症の高度肥満(10歳以前に発症し、体格指数が正常値より標準偏差3以上高いことで定義される)では、7%が1点のDNA変異を保有している。

特定の遺伝子ではなく、遺伝パターンに注目した研究によると、2人の肥満の親の子供の80%が肥満であったのに対し、標準体重の2人の親の子供は10%未満であった。同じ環境にさらされても、基礎にある遺伝によって肥満のリスクは異なる。

倹約遺伝子仮説は、人類が進化する過程で食事が乏しくなったために肥満になりやすくなったと仮定している。脂肪としてエネルギーを蓄えることで稀にある豊かな時期を利用する能力は、食料の入手可能性が変化する時期に有利であり、脂肪を多く蓄えた個体は飢饉を生き延びる可能性が高くなる。しかし、脂肪を蓄えるこの傾向は、食糧供給が安定している社会では不適応となる。この説は様々な批判を受けており、漂流遺伝子仮説や倹約的表現型仮説といった進化論に基づく他の説も提唱されている。

その他の病気

特定の身体的・精神的疾患およびその治療に用いられる医薬品は、肥満のリスクを高める可能性がある。肥満リスクを増加させる医学的疾患には、先天性または後天性の疾患だけでなく、いくつかのまれな遺伝的症候群(上記)が含まれる: 甲状腺機能低下症、クッシング症候群、成長ホルモン欠乏症、およびむちゃ食い障害や夜食症候群などのいくつかの摂食障害がある。しかし、肥満は精神疾患とはみなされていないため、DSM-IVRには精神疾患として記載されていない。過体重や肥満のリスクは、精神疾患のある患者では精神疾患のない患者よりも高い。肥満とうつ病は相互に影響し合い、肥満は臨床的うつ病のリスクを高め、またうつ病は肥満を発症する可能性を高める。

薬物誘発性肥満

特定の薬剤が体重増加または体組成の変化を引き起こすことがある; これらには、インスリン、スルホニルウレア、チアゾリジンジオン、非定型抗精神病薬、抗うつ薬、ステロイド、特定の抗けいれん薬(フェニトインおよびバルプロ酸塩)、ピゾチフェン、およびいくつかの形態のホルモン避妊薬が含まれる。

社会的決定要因

遺伝的な影響は肥満を理解する上で重要ではあるが、特定の国や世界的に見られる劇的な増加を完全に説明することはできない。エネルギー消費量がエネルギー消費量を上回ると、個人単位では体重が増加することは認められているが、社会規模でのこの2つの要因の変化の原因については、多くの議論がある。原因については諸説あるが、様々な要因が絡み合っているとする説が多い。

社会階級とBMIの相関関係は世界的に異なる。1989年の調査では、先進国では社会階層の高い女性は肥満になりにくいことがわかった。異なる社会階層の男性の間では、有意な差は見られなかった。発展途上国では、社会階層の高い女性、男性、子どもの肥満率が高かった。2007年にも同じ研究が繰り返され、同じような関係が見られたが、より弱いものであった。相関関係の強さの低下は、グローバリゼーションの影響によるものと考えられた。先進国では、成人の肥満度や10代の子どもの肥満率は、所得格差と相関している。同じような関係はアメリカの各州でも見られ、より不平等な州では、より高い社会階層であっても、より多くの成人が肥満である。

BMIと社会階層との関連については、多くの説明がなされている。先進国では、富裕層はより栄養価の高い食品を買う余裕があり、スリムであることを求める社会的プレッシャーが大きく、体力に対する期待が大きく、より多くの機会があると考えられている。未開発国では、食料を買う余裕があること、肉体労働によるエネルギー消費が大きいこと、より大きな体格を好む文化的価値観が、観察されたパターンに寄与していると考えられている。身近な人が持つ体重に対する態度も肥満に関与している可能性がある。BMIの経時的変化には、友人、兄弟姉妹、配偶者の間に相関関係がみられる。ストレスや社会的地位の低さは肥満のリスクを高めるようである。

喫煙は個人の体重に大きな影響を与える。禁煙した人は、10年間で男性で平均4.4kg、女性で平均5.0kg体重が増加する。しかし、喫煙率の変化は肥満率全体にはほとんど影響を及ぼしていない。

米国では、子供の数が肥満リスクと関係している。女性のリスクは子供1人につき7%増加し、男性のリスクは子供1人につき4%増加する。これは、扶養義務のある子供がいると、欧米の親の身体活動が低下するという事実からも説明できる。

発展途上国では、都市化が肥満率の増加に一役買っている。中国では、全体的な肥満率は5%以下だが、一部の都市では肥満率が20%を超えている。その一因として、都市設計の問題(身体活動のための公共スペースが不十分など)が考えられる。自転車や徒歩などの能動的な交通手段とは対照的に、自動車で過ごす時間は肥満リスクの増加と相関している。

幼少期の栄養失調は、発展途上国における肥満率の上昇に一役買っていると考えられている。栄養不良の期間に起こる内分泌の変化は、より多くの食物エネルギーが利用できるようになると、脂肪の蓄積を促進する可能性がある。

腸内細菌

感染因子が代謝に及ぼす影響に関する研究は、まだ初期段階にある。腸内細菌叢は、痩せた人と肥満の人では異なることが示されている。腸内細菌叢が代謝能に影響を及ぼす可能性が示唆されている。この明らかな変化は、肥満の一因となるエネルギーの収穫能力を高めると考えられている。このような違いが肥満の直接的な原因なのか、それとも結果なのかは、まだ明確に決定されていない。小児における抗生物質の使用も、その後の肥満と関連している。

ウイルスと肥満との関連は、ヒトやいくつかの異なる動物種で発見されている。これらの関連性が肥満率の上昇にどれだけ寄与しているかは、まだ明らかにされていない。

その他の要因

睡眠不足は肥満と関連している。一方が他方を引き起こすかどうかは不明である。短時間睡眠が体重増加を増加させるとしても、それが意味のある程度なのか、睡眠時間を増やすことが有益なのかは不明である。

肥満には「オベソゲン」と呼ばれる化学物質が関与しているという説もある。

性格のある側面は肥満であることと関連している。孤独感、神経症、衝動性、報酬に対する感受性は肥満の人に多く、良心性と自制心は肥満の人に少ない。このテーマに関する研究のほとんどは質問紙ベースであるため、これらの結果が性格と肥満の関係を過大評価している可能性がある:肥満の人は肥満の社会的スティグマを意識している可能性があり、それに応じて質問紙回答が偏っている可能性がある。同様に、子供の頃に肥満であった人の性格は、肥満の危険因子として働くというよりも、むしろ肥満のスティグマに影響されているかもしれない。

グローバリゼーションとの関連では、貿易自由化が肥満と関連していることが知られている。1975年から2016年の175カ国のデータに基づく調査では、肥満の有病率は貿易開放度と正の相関があり、その相関は発展途上国でより強いことが示された。

病態生理学

肥満の発症には、持続的な正のエネルギーバランス(エネルギー摂取量がエネルギー消費量を上回る)と、増加した体重の「セットポイント」のリセットという、2つの異なるが関連したプロセスが関与していると考えられている。2つ目のプロセスは、有効な肥満治療法の発見が困難であった理由を説明するものである。このプロセスの根底にある生物学的メカニズムはまだ不明であるが、研究によってそのメカニズムが解明されつつある。

生物学的レベルでは、肥満の発症と維持には多くの病態生理学メカニズムが関与している可能性がある。この研究分野は、1994年にJ.M.フリードマンの研究室によってレプチン遺伝子が発見されるまで、ほとんど手がつけられていなかった。レプチンとグレリンは末梢で産生されるが、中枢神経系への作用を通して食欲をコントロールしている。特に、これらのホルモンや他の食欲関連ホルモンは、脳の視床下部という食物摂取とエネルギー消費の調節の中心的な部位に作用する。視床下部には、食欲を統合する役割に寄与するいくつかの回路があるが、メラノコルチン経路が最もよく理解されている。この回路は、脳の摂食中枢である外側視床下部(LH)と満腹中枢である視床下部(VMH)への出力を持つ視床下部の領域、弧状核から始まる。

弧状核には2つの異なるニューロン群が存在する。第一のグループは神経ペプチドY(NPY)とアグーチ関連ペプチド(AgRP)を共発現し、LHへの刺激性入力とVMHへの抑制性入力を持つ。第二のグループはプロオピオメラノコルチン(POMC)とコカイン・アンフェタミン制御転写物(CART)を共発現し、VMHへの刺激入力とLHへの抑制入力を持つ。その結果、NPY/AgRPニューロンは摂食を刺激し満腹感を抑制し、POMC/CARTニューロンは満腹感を刺激し摂食を抑制する。弧状核ニューロンの両グループは、レプチンによって部分的に制御されている。レプチンはNPY/AgRP群を抑制する一方、POMC/CART群を刺激する。したがって、レプチン欠乏症またはレプチン抵抗性のいずれかを介したレプチンシグナル伝達の欠乏は、摂食過多を引き起こし、遺伝性肥満や後天性肥満の一部を説明する可能性がある。

管理

肥満の主な治療は、処方された食事や身体運動などの生活習慣への介入による減量である。どのような食事が長期的な体重減少をサポートするのかは不明であり、低カロリー食の有効性については議論があるが、長期的にカロリー消費を減らしたり、身体運動を増やしたりするライフスタイルの変化も、時間の経過とともに体重の戻りは緩やかであるものの、ある程度の持続的な体重減少をもたらす傾向がある。全米体重コントロール登録の参加者の87%が10年間10%の体重減少を維持することができたが、長期的な体重減少維持のための最も適切な食事療法はまだわかっていない。米国では、食事の変更と運動の両方を組み合わせた集中的な行動介入が推奨されている。間欠的絶食は、継続的なエネルギー制限と比較して、体重減少の追加的利益はない。減量を成功させるには、どのような食事療法を行うかよりも、アドヒアランスの方が重要である。

いくつかの低カロリー食は効果的である。短期的には、低炭水化物食の方が低脂肪食よりも体重減少に良いと思われる。しかし、長期的には、すべてのタイプの低炭水化物食と低脂肪食が等しく有益であるように見える。さまざまな食事に関連する心臓病と糖尿病のリスクは同程度のようである。肥満者における地中海食の推進は、心臓病のリスクを低下させるかもしれない。甘い飲み物の摂取量の減少も減量に関係している。生活様式の変更による長期的な体重減少維持の成功率は低く、2~20%である。食事および生活様式の変更は、妊娠中の過度の体重増加を制限するのに有効であり、母子ともに転帰を改善する。肥満と心臓病の他の危険因子を併せ持つ人には、集中的な行動カウンセリングが推奨される。

健康政策

肥満は、その有病率、コスト、健康への影響から、複雑な公衆衛生・政策問題である。そのため、肥満の管理には、より広い社会的背景の変化と、地域社会、地方自治体、政府による取り組みが必要である。公衆衛生の努力は、人口における肥満の有病率増加の原因となっている環境要因を理解し、是正しようとするものである。解決策は、過剰な食物エネルギー消費を引き起こし、身体活動を阻害する要因を変えることにある。取り組みとしては、連邦政府から払い戻しのある学校での給食プログラム、子どもたちへの直接的なジャンク食品販売の制限、学校での砂糖入り飲料へのアクセスの減少などがある。世界保健機関(WHO)は、砂糖入り飲料への課税を推奨している。都市環境を構築する際には、公園へのアクセスを増やし、歩行者ルートを整備する努力がなされてきた。

マスメディアのキャンペーンは、肥満に影響する行動を変える効果は限定的であるように思われる。同時に、運動や食事に関する知識や意識を高めることができ、長期的には変化につながるかもしれない。キャンペーンはまた、座っている、横になっている時間を減らし、身体的に活動する意思にプラスの影響を与えることができるかもしれない。メニューにエネルギー情報を記載した栄養成分表示は、レストランでの食事中のエネルギー摂取量を減らすのに役立つかもしれない。超加工食品に対する政策を求める声もある。

医療介入

薬物療法

1930年代に肥満治療薬が登場して以来、多くの化合物が試されてきた。そのほとんどは体重を微量に減少させるものであり、そのうちのいくつかは副作用のために肥満症治療薬として販売されなくなっている。1964年から2009年の間に市場から撤去された25種類の抗肥満薬のうち、23種類は脳内の化学物質神経伝達物質の機能を変化させることによって作用した。撤退に至ったこれらの薬の最も一般的な副作用は、精神障害、心臓の副作用、そして薬物乱用や薬物依存であった。7つの製品に関連した死亡例が報告されている。

長期使用に有益な薬は5つある: オルリスタット、ロルカセリン、リラグルチド、フェンテルミン/トピラマート、ナルトレキソン/ブプロピオンである。 その結果、1年後の体重減少は、プラセボを3.0~6.7kg(6.6~14.8ポンド)上回った。オルリスタット、リラグルチド、ナルトレキソン-ブプロピオンは米国と欧州の両方で入手可能であるが、フェンテルミン-トピラマートは米国でのみ入手可能である。ヨーロッパの規制当局はロルカセリンとフェンテルミン・トピラマートを拒絶したが、その理由の一つは、ロルカセリンでは心臓弁の問題が、ロルカセリンとフェンテルミン・トピラマートではより一般的な心臓と血管の問題が関連していたためである。ロルカセリンは米国で販売されていたが、がんとの関連から2020年に市場から削除された。オルリスタットの使用は高い確率で胃腸の副作用と関連しており、腎臓への悪影響が懸念されている。これらの薬剤が心血管疾患や死亡といった肥満の長期合併症にどのような影響を及ぼすかについての情報はないが、リラグルチドを2型糖尿病に使用した場合、心血管イベントは減少する。

2019年にシステマティックレビューで、肥満成人における様々な用量のフルオキセチン(60 mg/d、40 mg/d、20 mg/d、10 mg/d)の体重に対する効果が比較された。プラセボと比較すると、どの用量のフルオキセチンも体重減少に寄与するようであったが、治療期間中にめまい、眠気、疲労、不眠、吐き気などの副作用を経験するリスクが増加した。しかし、これらの結論は確実性の低いエビデンスによるものであった。同じレビューで、肥満成人の体重に対するフルオキセチンの効果を、他の抗肥満薬、オメガ-3ゲル、治療を受けていない場合と比較した場合、著者らはエビデンスの質が低いため、決定的な結果に到達できなかった。

統合失調症治療用の抗精神病薬の中でクロザピンは最も有効であるが、肥満が主な特徴であるメタボリックシンドロームを引き起こすリスクも最も高い。クロザピンの服用により体重が増加した人は、メトホルミンを服用することにより、メタボリックシンドロームの5つの構成要素のうち3つ(ウエスト周囲径、空腹時血糖、空腹時トリグリセリド)が改善すると報告されている。

手術

肥満に対する最も効果的な治療法は肥満手術である。手術の種類には、腹腔鏡下調節可能胃バンディング術、ルークス-エン-Y胃バイパス術、縦型スリーブ胃切除術、胆膵転換術などがある。高度肥満に対する手術は、長期的な体重減少、肥満に関連した病態の改善、および全死亡率の低下と関連している;しかしながら、代謝健康の改善は体重減少によるものであり、手術によるものではない。ある研究では、標準的な減量法と比較した場合、10年後の体重減少率は14%~25%(実施した手術の種類による)、全死因死亡率は29%減少した。合併症は約17%の症例で起こり、7%の症例で再手術が必要である。

疫学

See or edit source data.

それ以前の歴史的な時代には、肥満は健康上の問題としてすでに認識されていたものの、ごく一部のエリートによってのみ達成されるまれなものであった。しかし、近世に繁栄が進むにつれて、肥満はますます多くの人々に影響を及ぼすようになった。1970年代以前は、肥満は最も裕福な国でも比較的まれな状態であり、肥満が存在するとしても裕福な人々の間で起こる傾向があった。その後、さまざまな出来事が重なり、人間の状態が変わり始めた。第一世界の人々の平均BMIが上昇し始め、その結果、過体重や肥満の人の割合が急増したのである。

1997年、WHOは肥満を世界的な疫病として正式に認定した。2008年現在、WHOは少なくとも5億人(10%以上)の成人が肥満であり、男性よりも女性の方が肥満率が高いと推定している。1980年から2014年の間に、肥満の世界的有病率は2倍以上に増加した。2014年には、6億人以上の成人が肥満であり、これは世界の成人人口の約13%に相当する。2015-2016年現在のアメリカにおける成人の割合は、全体で約39.6%(男性37.9%、女性41.1%)である。2000年、世界保健機関(WHO)は、過体重と肥満が、栄養不足や感染症といった、より伝統的な公衆衛生の懸念に取って代わり、健康不良の最も重大な原因のひとつになっていると述べた。

また、肥満の割合は少なくとも50歳、60歳までは年齢とともに増加し、アメリカ、オーストラリア、カナダでは重度の肥満が全体の肥満率よりも速く増加している。OECDは少なくとも2030年まで肥満率が増加すると予測しており、特にアメリカ、メキシコ、イギリスではそれぞれ47%、39%、35%に達すると予測している。

かつては高所得国だけの問題と考えられていた肥満率が世界的に上昇し、先進国と発展途上国の両方に影響を及ぼしている。こうした増加は、都市部で最も顕著に現れている。

性別による違いも肥満の有病率に影響を与える。世界的には男性より女性の方が肥満者が多いが、その数は肥満の測定方法によって異なる。

歴史

語源

Obesityはラテン語のobesitasに由来し、「がっしりした、太った、ふくよかな」を意味する。Ēsusはedere(食べる)の過去分詞で、それにob(超える)が加わったものである。オックスフォード英語辞典'には1611年にRandle Cotgraveによって初めて使われたと記録されている。

歴史的姿勢

古代ギリシア医学は肥満を医学的疾患として認めており、古代エジプト人も同じように肥満を見ていたと記録している。ヒポクラテスは「肥大は病気そのものであるだけでなく、他の病気の前触れである」と書いた。インドの外科医スシュルタ(紀元前6世紀)は、肥満を糖尿病や心臓疾患と関連づけた。彼は肥満とその副作用を治すために肉体労働を勧めた。人類の歴史の大半において、人類は食糧不足と闘ってきた。そのため、肥満は歴史的に富と繁栄の証とみなされてきた。古代東アジア文明では、高官の間で一般的であった。17世紀、イギリスの医学者トビアス・ヴェナーは、出版された英語の本の中で、社会的な病気としてこの言葉を最初に言及した一人とされている。

産業革命が始まると、国家の軍事力と経済力が兵士や労働者の体格と体力の両方に左右されることがわかった。平均的な体格指数を現在の低体重とされるものから、現在の標準的な範囲まで高めることが、工業化社会の発展に重要な役割を果たした。こうして身長と体重は、先進国では19世紀を通じて増加した。20世紀には、集団が遺伝的に可能な身長に達すると、体重は身長よりもはるかに増加し始め、その結果肥満が生じた。1950年代には、先進国の富裕化が進み、子どもの死亡率は低下したが、体重が増加するにつれて、心臓病や腎臓病が多発するようになった。 この時期、保険会社は体重と寿命の関係に気づき、肥満者に対する保険料を値上げした。

歴史上、多くの文化が肥満を性格的欠陥の結果とみなしてきた。古代ギリシャの喜劇に登場するobesusつまり太った人物は大食漢であり、嘲笑の的であった。キリスト教時代には、食べ物は怠惰や欲望の罪への入り口と見なされていた。現代の西洋文化では、過剰な体重は魅力がないとみなされることが多く、肥満は一般的にさまざまな否定的なステレオタイプと結びついている。あらゆる年齢の人々が社会的汚名に直面し、いじめの標的にされたり、仲間から敬遠されたりすることがある。

健康的な体重に関する欧米社会の一般的な認識と、理想的とされる体重に関する認識は異なっており、両者は20世紀に入ってから変化している。理想とされる体重は、1920年代以降低くなっている。このことは、ミス・アメリカコンテスト受賞者の平均身長が1922年から1999年にかけて2%増加したのに対し、平均体重は12%減少したことからもわかる。一方、健康的な体重に関する人々の見方は逆に変化している。イギリスでは、自分が太りすぎだと思う体重は、1999年よりも2007年の方が大幅に増えている。このような変化は、脂肪率の増加により、余分な体脂肪が普通であると受け入れられるようになったためと考えられている。

アフリカの多くの地域では、肥満はいまだに富と幸福の証とみなされている。特にHIVの流行が始まって以来、その傾向が強くなっている。

芸術

20,000~35,000年前の人体の最初の彫刻表現は、肥満した女性を描いている。このヴィーナスの彫刻を、豊穣を強調する傾向のためとする人もいれば、当時の人々の「太りやすさ」を表していると感じる人もいる。しかし、ギリシア・ローマ美術には豊満さが見られない。この傾向は、キリスト教ヨーロッパの歴史の大半を通じて続き、社会経済的地位の低い人々だけが肥満として描かれた。

ルネサンス期には、イギリスのヘンリー8世やアレッサンドロ・ダル・ボッロの肖像画に見られるように、上流階級の一部が大柄であることを誇示し始めた。ルーベンス(1577年-1640年)は定期的に大柄な女性を描いており、そこからルーベネスクという言葉が生まれた。しかし、これらの女性たちは、豊穣と関係のある「砂時計」の形を維持していた。19世紀、西洋世界では肥満に対する見方が変わった。何世紀にもわたって肥満が富と社会的地位の代名詞とされてきた後、スリムであることが望ましい標準とみなされるようになった。1819年の版画「The Belle Alliance, or the Female Reformers of Blackburn!!!」で、画家George CruikshankはBlackburnの女性改革者たちの活動を批判し、彼女たちを女性らしくないと描く手段として太り方を用いた。

社会と文化

経済的影響

健康への影響に加え、肥満は雇用の不利やビジネスコストの増加など、多くの問題を引き起こす。こうした影響は、個人、企業、政府など、社会のあらゆるレベルで感じられる。

2005年、米国における肥満に起因する医療費は推定1,902億ドル(全医療費の20.6%)、カナダにおける肥満のコストは1997年に推定20億カナダドル(総医療費の2.4%)であった。2005年のオーストラリアにおける過体重と肥満の年間直接費用は合計210億豪ドルであった。また、過体重・肥満のオーストラリア人は、356億豪ドルの政府補助金を受け取っている。ダイエット製品への年間支出額の推定範囲は、米国だけで400億ドルから1,000億ドルである。

ランセット誌 2019年の肥満に関する委員会は、WHOたばこ規制枠組条約をモデルとして、肥満と栄養不足に対処することを各国に約束し、政策立案から食品業界を明確に除外した世界的な条約を求めた。彼らは、肥満の世界的なコストは年間2兆ドル、世界GDPの約2.8%と見積もっている。

肥満予防プログラムは、肥満に関連した病気の治療費を削減することが分かっている。しかし、長生きすればするほど医療費は増える。したがって研究者たちは、肥満を減らすことは国民の健康を改善するかもしれないが、医療費全体の支出を減らす可能性は低いと結論づけている。食習慣や消費習慣を抑制し、経済的負担を相殺する努力として、砂糖入り飲料税のような罪税が世界的に特定の国で実施されている。

肥満は社会的汚名を着せられ、雇用面でも不利になる。標準体重の労働者と比較すると、肥満の労働者は平均して欠勤率が高く、障害休暇を多く取るため、雇用者のコストが増加し、生産性が低下する。デューク大学の従業員を調査した研究によると、BMIが40 kg/m2を超える人は、BMIが18.5-24.9 kg/m2の人に比べて、2倍の労災請求を行った。また、労働損失日数も12倍以上であった。このグループで最も多かった怪我は転倒と持ち上げによるもので、下肢、手首または手、背中に影響を及ぼしていた。アラバマ州職員保険委員会は、肥満の労働者に対し、減量と健康改善のための措置を講じない限り、本来無料であるはずの健康保険料を月25ドル徴収する計画を承認し、物議を醸している。この措置は2010年1月から開始され、BMIが35 kg/m2を超え、1年経っても健康状態の改善が見られない州職員に適用される。

肥満の人は採用されにくく、昇進しにくいという調査結果もある。また、肥満の人は肥満でない人に比べて、同等の仕事をした場合の給与が低く、肥満の女性は平均で6%、肥満の男性は3%低い。

航空業界、医療業界、食品業界など、特定の業界には特別な懸念がある。肥満率の上昇により、航空会社は燃料費の上昇と座席幅を広げる圧力に直面している。2000年には、肥満の乗客の体重増加により、航空会社は2億7500万米ドルの損失を被った。医療業界は、特別なリフト装置や肥満救急車など、重度の肥満患者を扱うための特別な設備に投資しなければならなくなった。レストランは、肥満の原因を作ったとする訴訟により、コストが増大している。2005年、アメリカ議会は肥満に関する食品業界への民事訴訟を防ぐための法案を審議したが、法制化には至らなかった。

2013年にアメリカ医師会が肥満を慢性疾患に分類したことで、健康保険会社が肥満の治療やカウンセリング、手術の費用を負担する可能性が高まり、脂肪治療薬や遺伝子治療法の研究開発費も、保険会社がその費用を補助することでより手頃な価格になると考えられている。ただし、AMAの分類には法的拘束力はないため、医療保険会社には治療や処置の保険適用を拒否する権利が残っている。

2014年、欧州司法裁判所は、病的肥満は障害であるとの判決を下した。同裁判所は、従業員の肥満が「他の労働者と対等な立場での職業生活への完全かつ効果的な参加」を妨げる場合、それは障害とみなされ、そのような理由で解雇することは差別的であるとした。

低所得国では、肥満は富のシグナルとなりうる。2023年の実験的研究によると、ウガンダでは肥満の人ほどクレジットを利用しやすいことがわかった。

サイズの受容

脂肪受容運動の主な目的は、太りすぎや肥満の人に対する差別を減らすことである。しかし、この運動の中には、肥満と健康上の悪い結果との間に確立された関係に異議を唱えようとするものもある。

肥満の容認を推進する団体は数多く存在する。それらは20世紀後半にその存在感を増してきた。米国を拠点とする全米ファット・アクセプタンス推進協会 (NAAFA)は1969年に結成され、サイズ差別をなくすことを目的とした公民権団体であると自称している。

国際サイズ受容協会(ISAA)は1997年に設立された非政府組織(NGO)である。よりグローバルな方向性を持ち、サイズ受容を促進し、体重による差別をなくすことを使命としている。これらの団体はしばしば、アメリカの障害者自立支援法(ADA)の下で肥満を障害として認めるよう主張している。しかし、アメリカの法制度は、この差別禁止法を肥満にまで拡大するメリットを、潜在的な公衆衛生上のコストが上回ると判断している。

業界による研究への影響

2015年、ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙は、2014年に設立された非営利団体グローバル・エネルギー・バランス・ネットワークに関する記事を掲載した。この団体は、肥満を回避し、健康であるためには、摂取カロリーを減らすことよりも、運動を増やすことに重点を置くべきだと提唱している。この団体はコカ・コーラ社から少なくとも150万ドルの資金提供を受けて設立され、同社は2008年以来、設立者の2人の科学者グレゴリー・A・ハンドとスティーブン・ブレアに400万ドルの研究資金を提供している。

報告書

多くの団体が肥満に関する報告書を発表している。1998年、「成人の過体重および肥満の同定、評価、治療に関する臨床ガイドライン」と題する米国初の連邦ガイドラインが発表された: "The Evidence Report"と題された。2006年、カナダ肥満ネットワーク(現在は肥満カナダとして知られる)は、"成人および小児の肥満の管理と予防に関するカナダの臨床実践ガイドライン(CPG)"を発表した。これは、成人および小児の過体重と肥満の管理と予防に対処するための包括的なエビデンスに基づくガイドラインである。

2004年、イギリスの王立医師会、公衆衛生学部、王立小児科・小児保健大学は、報告書「Storing up Problems」を発表し、イギリスにおける肥満問題の深刻化を強調した。同年、英国下院健康特別委員会は、肥満が英国の健康と社会に与える影響と、この問題に対する可能なアプローチについて、「これまでで最も包括的な調査[...]」を発表した。2006年、National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence|NICEは、肥満の診断と管理に関するガイドラインを発表し、地方議会のような非医療機関への政策的影響についても言及した。2007年にデレク・ワンレスがキングス・ファンドのために作成した報告書は、さらなる対策を講じない限り、肥満は国民保健サービスを財政的に衰弱させる可能性があると警告した。2022年、国立医療介護研究機構(NIHR)は、肥満を減らすために地方自治体ができることに関する研究の包括的なレビューを発表した。

肥満政策アクション(OPA)の枠組みでは、対策を「上流」政策、「中流」政策、「下流」政策に分けている。上流の政策は社会を変えることに関係し、中流の政策は個人レベルで肥満の原因と考えられる行動を変えようとするもので、下流の政策は現在肥満の人を治療するものである。

小児肥満

健康なBMIの範囲は、子供の年齢と性別によって異なる。小児および青年の肥満は、BMIが95パーセンタイルパーセンタイル以上と定義される。これらのパーセンタイルが基づく基準データは1963年から1994年までのものであるため、最近の肥満率の増加の影響は受けていない。小児肥満は21世紀に入って流行の兆しを見せており、先進国でも発展途上国でも肥満率が上昇している。カナダの男児の肥満率は、1980年代の11%から1990年代には30%以上に増加し、同じ期間にブラジルの子供たちの肥満率は4%から14%に増加した。イギリスでは、1989年と比較して2005年には60%も肥満の子供が増えている。アメリカでは、太りすぎと肥満の子供の割合は2008年には16%に増加し、それ以前の30年間で300%増加した。

成人の肥満と同様、小児肥満の増加にも多くの要因がある。食生活の変化と運動量の減少が、最近の子どもの肥満率増加の2大原因と考えられている。また、子どもへの不健康な食品の広告も、子どもの消費量を増加させるため、寄与している。生後6ヵ月間の抗生物質は、7~12歳時の体重超過と関連している。小児期の肥満はしばしば成人期まで持続し、多くの慢性疾患と関連するため、肥満の子どもはしばしば高血圧、糖尿病、高脂血症、脂肪肝疾患の検査を受ける。

小児に使用される治療法は、主に生活習慣への介入と行動テクニックであるが、小児の活動性を高める努力はほとんど成功していない。米国では、この年齢層に使用する薬剤はFDAに承認されていない。プライマリケアにおける短時間の体重管理介入(例えば、医師またはナースプラクティショナーによる)は、小児の過体重または肥満の減少においてわずかなプラスの効果しかない。食事と身体活動の変更を含む多成分の行動変容介入は、6~11歳の小児において短期的にBMIを低下させる可能性があるが、有益性は小さく、エビデンスの質も低い。

その他の動物

ペットの肥満は多くの国で見られる。アメリカでは、犬の23~41%が太りすぎで、約5.1%が肥満である。猫の肥満率は6.4%とやや高い。オーストラリアでは、獣医学的環境における犬の肥満率は7.6%であることが判明している。犬の肥満リスクは飼い主が肥満であるかどうかに関係しているが、猫と飼い主の間には同様の相関関係はない。

こちらも参照

さらに読む

- "Obesity 2015". The Lancet. 2015.

Series from the Lancet journals

- Jebb S, Wells J (2005). "Measuring body composition in adults and children". In Kopelman PG, Caterson ID, Stock MJ, Dietz WH (eds.). Clinical obesity in adults and children: In Adults and Children. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 12–28. ISBN 978-1-4051-1672-5.

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) (1998). Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults (PDF). International Medical Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-1-58808-002-8.

- "Obesity: guidance on the prevention, identification, assessment and management of overweight and obesity in adults and children" (PDF). National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence(NICE). National Health Services (NHS). 2006. Retrieved 8 April 2009.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2000). Technical report series 894: Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic (PDF). Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 978-92-4-120894-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 May 2015. Retrieved 10 May 2006.

外部リンク

Quotations related to Obesity at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Obesity at Wikiquote- WHO fact sheet on obesity and overweight